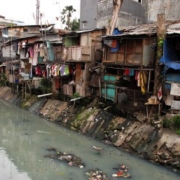

Although he is popular with the public, human rights organisations have slammed Ahok’s forceful efforts to impose law and order. Photo by Steven Fitzgerald Sipahutar.

Basuki Tjahaja Purnama is the governor of Jakarta. Most Indonesians know him as Ahok, a nickname derived from his Hakka Chinese name, Tjung Ban Hok. Whatever you want to call him, it is clear that he has made plenty of enemies. His strong stance against corruption and straight-talking style has made him popular with the public but left him without friends in the Jakarta legislature. There is even a chance that he won’t secure the backing of a political party to run for a second term as governor, and will have to stand as an independent, relying on public support.

Ahok’s feisty approach to politics was built over years of struggling up the ranks as one of the earliest Chinese Indonesians to hold a senior political position in the democratic era. Ahok was born in Manggar, East Belitung, in 1966. In 1989, he graduated from Trisakti University in Jakarta with a Bachelor of Geological Engineering, and later gained a Master of Business Administration (MBA). In between, he attempted to set up a quartz sand company in Belitung. Ahok has said he wanted to enter politics because of his frustration with corrupt bureaucracy while in business.

Ahok’s first political appointment was as a member of the East Belitung Legislative Council (DPRD) in 2004. He then went on to serve as district head of East Belitung, a position he held from August 2005 to December 2006, and became a member for Bangka-Belitung in the House of Representatives (DPR) from October 2009 to April 2012. He is not the only member of his family in politics. His brother, Basuri Tjahaja Purnama (Yuyu), is the East Belitung district head and his sister, Fifi Lety Tjahaja Purnama, ran unsuccessfully for Pangkal Pinang district head in 2008.

As governor of Jakarta, Ahok recently locked horns with the Jakarta City Council when he claimed the council’s draft 2015 budget contained wasteful spending not in his administration’s proposal – the original budget of Rp 78 trillion (AU$7.9 billion) had swelled to Rp 90 trillion (AU$9.1 billion). When Ahok submitted his original budget to the Ministry of Home Affairs, without the councillors’ approval, the council threatened to impeach him. Jusuf Kalla, the vice-president, intervened, however, and the councillors agreed to set a lower budget, which was finally approved by the ministry in April 2015. Public support for Ahok was overwhelming. For days, Twitter users mocked one of his main attackers in the legislature, Abraham Lunggana (also known as Haji Lulung), using the hashtag #savehajilulung.

Ahok is the first openly ethnic Chinese and Christian governor of Jakarta. (Henk Ngantung, the seventh governor of Jakarta, who served from 1964-65, was reportedly of Chinese descent and Catholic.) Both Ahok’s religion and his ethnicity have made him the target of racist attacks. In 2012, when campaigning as deputy governor with Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, he was subject to blatant racist taunts from his rival candidates, and a video circulated warning a repeat of the 1998 anti-Chinese violence if ethnic Chinese voted in the election. But he remains proud of his ethnicity. When campaigning in Bangka-Belitung, one of his campaign photos showed him in a Mandarin outfit and he often jokingly refers to himself as a kafir, or infidel.

The hard-line Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) also demonstrated violently against his inauguration as governor, stating that as an ethnic Chinese and Christian, he should not be allowed to lead the Muslim-majority capital. Larger mainstream Muslim organisations, however, have not protested against their Christian governor. The public, too, seems untroubled by Ahok’s ethnicity, happy to finally have a leader prepared to tackle bureaucratic waste and corruption.

The opposition Ahok has faced from groups like the FPI has not made him timid. On the contrary, he has openly expressed his opinion on a wide range of topics, many controversial. Most of his attitudes are progressive, although his views on law and order fall more on the conservative side. He has spoken in favour of sex education for teenagers and legalising prostitution in certain areas (as did one of his predecessors, Ali Sadikin, governor from 1966-77). In March 2015, in the lead-up to the executions of (mainly foreign) drug couriers, Ahok visited a prison and announced his support for abolition of the death penalty.

Ahok is a strong supporter of interfaith dialogue and minority rights. Having been raised in a predominantly Muslim region, he attended Islamic schools, has a good understanding of Islam and as governor has participated in many Muslim functions. Ahok has also, however, intervened to protect places of worship for Christians and the Ahmadi sect and has supported the removal of religious affiliation on the national identity card (KTP). In July, he ordered that the South Jakarta mayor and spatial planning agency reopen a shuttered Ahmadiyah mosque in Tebet. Justifying the move, Ahok referred to article 28E of the Indonesian Constitution, which explicitly guarantees freedom of religion.

Ahok is introducing a number of new computerised systems to improve data transparency and limit opportunities for corruption. These include a smart card for students; a licencing system for street vendors and a system that allows rent for low cost apartments to be paid directly to the city-owned Bank DKI. The administration plans to produce 7,200 low-cost apartments in 2015.

With Jokowi, Ahok introduced a number of regulations to strengthen law and order in the capital. These have included by-laws against littering, giving money to beggars, jaywalking, riding a motorbike without a helmet, driving without a licence and, for minibuses, stopping at unofficial bus stops. A website was set up, tertiblantas.com, where members of the public could post photos of people breaking the law. Traffic officers would check the photos and issue tickets. (Perhaps the size of the task was overwhelming, as the website no longer appears active). Public transport is being upgraded and, controversially, Ahok proposes banning motorbikes from certain roads.

Human rights organisations have, however, slammed Ahok’s forceful methods to impose law and order. The National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) criticised the way that squatters at Pluit Dam were forcibly removed to make way for flood prevention works. The Indonesian Commission for Child Protection (KPAI) criticised Ahok for supporting the expulsion of bullies or disruptive students, thereby depriving them of education. His suggestion to place snipers on street corners to shoot street thugs (preman) and criminals brought back dark memories of the petrus killings of Soeharto’s New Order period.

Ahok has shown little party loyalty during his time in politics. He was a member for the New Indonesia Alliance Party (PPIB) in the East Belitung DPRD and then switched to Golkar Party to represent Bangka-Belitung in the DPR. When he stood for deputy governor in 2012, he was backed by Gerindra (the Greater Indonesia Movement Party), the party of Prabowo Subianto. In September 2014, however, Ahok left Gerindra in protest over the party’s support for a bill to end direct elections for regional leaders.

Ahok only became governor because his predecessor, Jokowi, was elected president last year. Now his abrasive style and clean approach to politics have left him fighting alone. Although the next governor’s election is still two years away, his supporters are now scrambling to collect copies of one million identity cards so that he can register as an independent candidate. A group, “Friends of Ahok” has been set up to administer the process and by mid-July this year, 10,262 photocopies of supporters’ identity cards had already been collected. Ahok’s friends are as enthusiastic in their support of him as his enemies are in their criticism.