Anti-Chinese sentiment has surged over recent years, as incumbent Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) has prepared to run again in 2017. Photo by Muhammad Adimaja for Antara.

A few weeks ago a video circulated on social media showing Soeharto era dissident Sri Bintang Pamungkas calling Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahya Purnama (“Ahok”) a “Chinese bastard” (Cina brengsek). Bintang has form in this area. In an earlier interview with the Islamist website VOA Islam, Bintang claimed that China’s desire to conquer Indonesia extended back to the time of the Sriwijaya kingdom in the seventh century. He said he believed this desire had only become stronger with the election of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo (who he also claims is Chinese), with Ahok, he says, as his right hand man.

The racist maxim that “Not all Chinese people are bastards, but X is a bastard” is commonly heard in Indonesia. Former General Johannes Suryo Prabowo wrote on Facebook: “If you care about your ethnic Chinese friends, please remind them that the Chinese should not get too big for their boots (sok jago) when they are close to power. Think about the other ethnic Chinese who are good people but are poor. If anyone were to slaughter the Chinese or loot their homes and businesses, they wouldn’t be able to escape overseas [like the wealthy Chinese]”.

This statement is typical in that it divides ethnic Chinese into two categories: “Chinese who are too big for their boots” and “good Chinese”. Such things can never be measured, of course, and, more to the point, no ethnicity in the world has inherently good or inherently bad characteristics. This discursive distinction reinforces the essentialist view that Chinese are inherently “too big for their boots” and as a consequence, the riots, mass anger, and murders of ethnic Chinese that have occurred throughout Indonesian history are somehow justified.

This victim blaming is not only perpetrated by the majority community but, ironically, by the victims themselves. Responding to the criticism of Ahok, traditional medicine (jamu) entrepreneur Jaya Suprana wrote an open letter to Ahok in Sinar Harapan daily. The letter stated: “It is no secret, indeed it is a historical fact, that racially motivated violence has occurred repeatedly in Indonesia. A few rotten apples have spoiled the bunch. Because of the behaviour of a few ethnic Chinese individuals that makes them worthy of hatred, all ethnic Chinese citizens are treated the same, and considered worthy of hatred.”

Anti-Chinese sentiment has deep roots in Indonesian society but tends to fluctuate in line with political developments. It has surged over recent times, along with Ahok’s policies and his plans to run again for governor in 2017. When Ahok replaced Joko “Jokowi” Widodo as governor, many saw it as a bright spot for Indonesian democracy and tolerance. It was the first time in history that an openly ethnic Chinese Indonesian had held a post as important and strategic as the governor of the capital city. Indeed, many people saw the 2014 presidential election as a de facto election for the Jakarta governor’s post, knowing that if Jokowi was successful, Ahok would take his place. Supporters of pluralism and tolerance felt they would be creating history by supporting Ahok as governor.

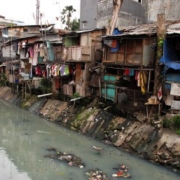

Although widely considered to have firmly defended clean and transparent governance, Ahok is not without detractors. Criticism of Ahok originates from three main groups in society. The first includes human rights, environmental and anti-corruption activists. Their main grievances with Ahok are that his policies are biased toward the middle class and that he appears unsympathetic to poor Indonesians evicted from informal settlements. The human rights community has been distinctly uncomfortable with statements he has made that often ignore human rights principles – for example, his proposal to shoot criminals on the streets. Environmental activists, meanwhile, have criticised him for his plans for reclamation of Jakarta Bay. Anti-corruption activists have likewise begun to question his commitment to clean governance after he was questioned as a witness in corruption cases involving the Sumber Waras Hospital and the Jakarta Bay reclamation project.

The second group of critics comprises political parties, including the Greater Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra), which supported his run for deputy governor in 2012. The last group is comprised of the Islamic social organisations that reject Ahok for primordial reasons. They oppose Ahok simply because they refuse to be led by a kafir (non-Muslim). Ahok’s political party critics have shown that they are not against relying on the backing of this third group to attack Ahok.

Nevertheless, heading toward the governor’s election in 2017, surveys continue to show that Ahok is way out in front of any of his competitors. The criticism does not seem to have benefited any of his opponents. But that does not mean it has been completely impotent. There are now considerable divisions in civil society about whether to support Ahok, and a number of Jokowi’s volunteers and pro-Jokowi civil society organisations have also refused to support Ahok again. The fact that Jokowi is Ahok’s main political patron has not been enough to make them want to support him. Despite the validity and strength of the criticisms of Ahok, his opponents in Islamic organisations and political parties have fallen back on the easy options – race and religion.

Why has Ahok remained so popular with the public despite all the attacks he faces? First, Jakarta electors are relatively more educated and supportive of tolerance. For them, voting for Ahok is a way of expressing support for a new way of doing politics. The stronger the racist attacks against Ahok, the stronger their support for the incumbent governor. Second, following years of experience under other governors, Jakarta residents understand that Jakarta has large, complex problems that cannot be solved by one person in a short period. The experience of residents in facing Jakarta’s regular challenges – like routine floods, traffic congestion and pollution – puts Ahok’s weaknesses into perspective for many residents. Third, there is the view that despite Ahok’s weaknesses, the other candidates have far greater problems. Fourth, the fact that Ahok’s opponents have joined forces with the anti-democratic Hizbut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) and violent groups such as the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) and the Betawi Brotherhood Forum (FBR) has turned off progressive voters. The participation of groups like FPI, FBT and HTI on the frontline of anti-Ahok campaigns has, in fact, drowned out the human rights and anti-corruption criticisms.

It is in this dead-end that racial and religious issues have found a place. Ahok’s opponents, particularly from Islamic organisations and political parties, are not able to broaden their support to defeat him. As a result, they have chosen to ramp up base-level appeals to primordial issues. This is why anti-Chinese sentiment has continued to grow on social media over the past two years. Racism, in this context, is no more than a sign of Ahok’s opponents’ inability to formulate more effective criticism and organise an alternative political movement. The anti-Chinese propaganda will expand and strengthen if Ahok manages to win the governor’s role next year – and even more if he stands as Jokowi’s running mate two years later, as many predict.