Some 20,538 seats will be contested by about 300,000 candidates in the 2019 elections. Photo by M Agung Rajasa for Antara.

Indonesia is preparing to embark on the biggest, most complex one-day election in the world. The size and complexity of these elections means unfairness is an ever-present threat in all aspects of the process.

For the first time, legislative and presidential elections will be held on the same day: 17 April 2019. The numbers are staggering. About 187.1 million voters (comprised of 185.1 domestic and 2 million overseas voters) are eligible to cast their vote in one of 805,062 polling centres. In total, 20,538 seats are being contested by 300,000 candidates.

The most prominent sources of unfairness relate to voter rights to information, as well as the right to participate and be elected. The following runs through some of the most pressing concerns for the 2019 election.

Access to information

On the same day, at the same time, at the same polling centre, each voter will cast votes for public officials at five levels of political office: 1) president and vice president; 2) a member of the People’s Representative Council (DPR); 3) a member of the Regional Representatives Council (DPD); 4) a member of the Provincial Legislative Council (DPRD Provinsi); and 5) a member of the City/District Legislative Council (DPRD Kota/Kabupaten). For this reason, the election has been dubbed the “five boxes” election.

Given the size and complexity of the process, voters face considerable difficulty in obtaining clear and sufficient information about the elections, candidates, regulations and consequences of not participating.

Information regarding the profiles and backgrounds of candidates is limited. Voters must identify about 250-450 candidates in the electoral district where they will vote. Many candidates are not willing to publish detailed biographies on the official General Elections Commission (KPU) website. How can voters be expected to be cast their vote deliberately and rationally?

Voter eligibility

A second major concern relates to voter eligibility. Law 7 of 2017 on Elections (sometimes called the omnibus elections law) defines a voter as any eligible citizen who has reached the age of 17 or has married and holds an electronic identification card (e-KTP). Notably, only e-KTP holders can be registered on the electoral roll.

This stipulation may exclude many citizens from the election. In Papua, for example, less than 50 per cent of eligible voters have an e-KTP. It is estimated that more than 1.5 million eligible citizens will not be able to vote simply because they don’t have an e-KTP.

Voters in correctional institutions, social housing, conflict areas, agricultural plantations and mining sites, the urban poor who do not possess legal land tenure certificates, and indigenous and traditional belief communities also face the possibility of being denied their voting rights because of the e-KTP requirement.

A report published by the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago (AMAN) states that about 1.6 million indigenous people may not be able to vote in 2019 because they don’t hold e-KTPs.

The e-KTP requirement was introduced to prevent voter fraud, for example, people voting multiple times, or “ghost voters”. The proposal was encouraged by the government and major parties in the DPR (Golkar, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), and the Democratic Party) during deliberations on the 2017 Election Law.

The Ministry of Home Affairs promised to complete the e-KTP roll-out by December 2018. Whether it will meet this target is another question. It once pledged to complete the project by December 2012 but the massive corruption that eventually put DPR Chair Setya Novanto in prison saw this deadline extended.

Presidential threshold

The 2017 Election Law also disadvantages the four parties that are participating in legislative elections for the first time: the Change Indonesia Movement Party (Garuda), the Working Party (Berkarya), the Indonesian Unity Party (Perindo) and Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI).

Under the Law, political parties must have secured a minimum 20 per cent of seats or 25 per cent of valid votes during the last national legislative election in 2014.

This means new parties have no right to nominate a presidential or vice presidential candidate. They can only participate as supporting parties and their party logos will not be displayed on the ballot paper like other parties.

The introduction of the presidential nomination threshold was intended to simplify the election process, but it has also led to several negative impacts.

Political recruitment has become more elitist. Presidential candidates are selected based on horse-trading and pragmatic calculations about meeting the threshold rather than their ideas or programmatic proposals. This disadvantages younger and female candidates in particular.

Some observers in Indonesia believe that political polarisation has become pronounced over the past two elections because there have only been two presidential candidates. The country has seen a rapid escalation in the use of hoaxes, fake news, and disinformation – much of it spread by the passionate supporters of the two opposing candidates.

Women candidates

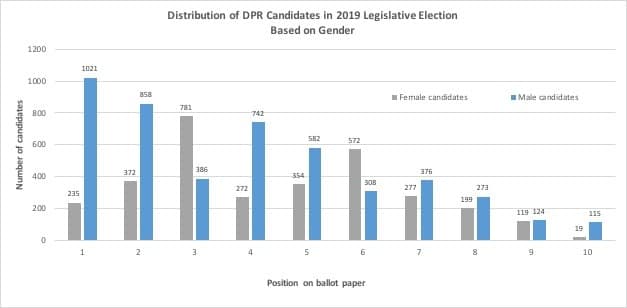

Since the 2004 legislative elections, parties have been required to field at least 30 per cent female candidates and distribute them evenly on the ballot paper to participate in an electoral district. Some 40 per cent of candidates in the 2019 legislative elections are women.

Although Indonesia uses an “open-list” system, meaning voters can rank candidates from a party according to their own preference rather than simply selecting the party, the majority of winners in DPR and DPRD elections (80 per cent) are from position 1 or 2. Most female candidates, meanwhile, are typically nominated in positions 3 or 6.

This might explain why the proportion of women in the DPR following the 2009 and 2014 elections was only 18 per cent, despite the 30 per cent requirement for candidates.

Campaign financing

Money plays a major role in Indonesia’s elections. There is very weak transparency and accountability of campaign financing. Oversight is poor and enforcement of existing regulations is weak.

Despite these problems, the 2017 Election Law dramatically increases the upper limit for campaign donations. The upper limit for individual donations has increased from Rp 1 billion to Rp 2.5 billion and for organisations from Rp 7.5 billion to Rp 25 billion. There is no limit on cash donations.