Protesters demand Jakarta Governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama is arrested and tried over allegations of blasphemy. Photo by Nova Wahyudi for Antara.

How much will religion influence the choice of voters in the Jakarta gubernatorial election scheduled for 15 February? Following the massive rallies against incumbent Jakarta Governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama over his alleged blasphemous remarks, one might assume that religion was the most important factor for electors. On the weekend, for example, an estimated 100,000 Indonesian Muslims gathered for a “mass prayer” at Istiqlal Mosque in Central Jakarta, where they were urged to vote for a Muslim governor. But the data tells another story.

I recently conducted a survey to determine the extent that so-called SARA issues (ethnicity, religion, race, and other social divisions) influence voter support for Ahok. Previous surveys have been unable to answer this question satisfactorily because they ask the wrong questions. They ask respondents: “What are some of the factors that influence your voting preference?” or “Does a candidate’s ethnicity or religion influence your support for him?”

This is a naïve way to probe such a sensitive issue. Many respondents are unlikely to want to admit that they are swayed by ethnic or religious sentiments. Even if they are not embarrassed, they may not recognise the degree to which unconscious ethnic or religious biases influence their decisions.

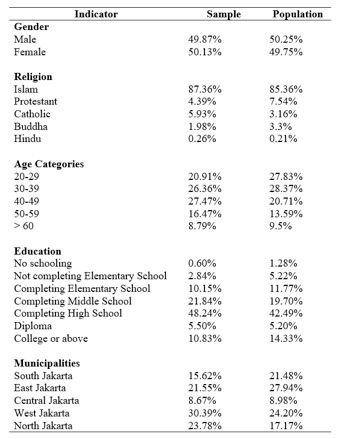

To avoid these difficulties, I conducted a survey experiment to estimate the effect of Ahok’s ethnicity and religion on voting intention by holding other factors constant through randomisation. The survey was conducted between the middle of November and early December (the peak of anti-Ahok sentiment). A stratified random sampling method was used to obtain a sample of Jakarta residents aged 18 or older. A total of 1,163 Jakarta residents were reached when first contacted by interviewers. I excluded non-Muslim respondents and analysed the results of the 1,016 Muslim respondents who took part. It should be noted that the primary purpose of the survey was not to predict votes for particular candidates, as most surveys do. My primary concern was with the internal validity or causal relationship, and not with the external validity or generalisability of the results. Nonetheless, as the figure below demonstrates, the characteristics of the sample group were largely consistent with the characteristics of the population in Jakarta, which improves confidence in the generalisability of the study.

Characteristics of the survey sample compared to the Jakarta population.

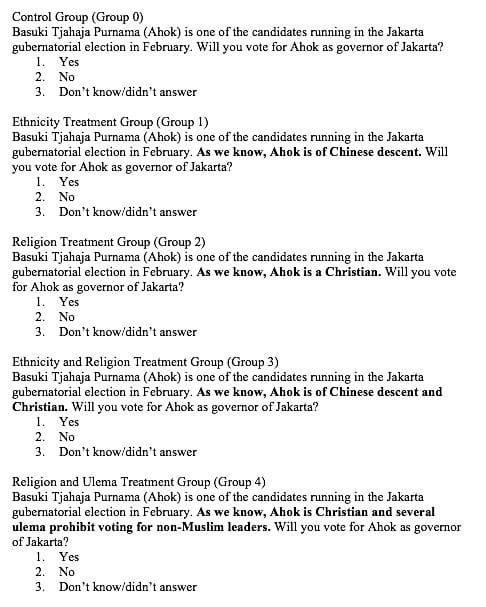

To conduct the survey, I randomly assigned respondents into five groups, with each respondent belonging only to one group. Each group was presented with a differently worded question. A control group served as a baseline. The control group aimed to assess support for Ahok where they were not explicitly reminded of his religion or ethnicity. Respondents in the ‘ethnicity’ group were reminded that Ahok is of Chinese descent. The ‘religion’ group were reminded that Ahok is Christian. The ‘ethnicity and religion’ group were reminded that Ahok is of Chinese descent and Christian. Finally, the ‘religion and ulema’ group were reminded that Ahok is Christian and some religious leaders forbid Muslims to vote for a non-Muslim.

Questions asked to each sample group.

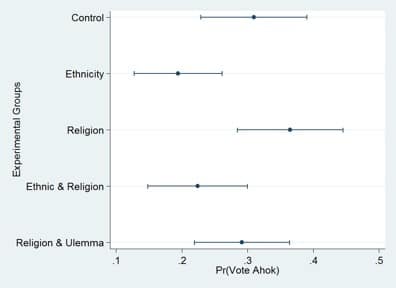

Thanks to randomisation, analysis of the results was straightforward. To estimate the effects of reminding respondents of Ahok’s ethnicity, religion, and the advice from some religious leaders, we only need to compare levels of support in the four treatment groups against the level of support in the control group. The predicted probabilities of support for Ahok in each group are presented below, shown along with their 95 per cent confidence interval (meaning that if the same population were sampled on multiple occasions, 95 per cent of the time such an interval would cover the true level of support for Ahok—which we do not know unless we ask the whole population). Put simply, if the predicted level of support for Ahok in a group (represented by the dot in the middle of the interval) overlaps with another group’s confidence interval, that means that levels of support in the two groups are not statistically different and any apparent difference is likely caused by sampling error.

Predicted probabilities of support for Ahok.

Baseline support for Ahok was about 30 per cent, as indicated by the level of support in the control group. There is no statistically significant difference between the level of support in the control group and the levels of support of in the last three groups. In other words, reminding respondents that Ahok is a Christian did not significantly decrease or increase support for Ahok. Even respondents who were reminded that some religious leaders forbid Muslims from voting for a non-Muslim leader did not display lower levels of support for Ahok. But there is a 10 per cent decrease in levels of support for Ahok among respondents who were reminded that Ahok is of Chinese descent.

So SARA concerns clearly matter in the Jakarta election. But it is not religion that matters the most – it is ethnicity. More respondents reject Ahok because he is of Chinese descent than because he is Christian.

There has recently been a surge in anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia, particularly online. In December, for example, President Joko Widodo was forced to counter widespread rumours that he had plans to bring in more than 10 million Chinese workers to the country. This anti-Chinese sentiment is partly a legacy of the policies of former President Soeharto, which saw Chinese Indonesians treated like second-class citizens for more than three decades. It has picked up with the rise of Ahok and the growing influence of China in the region.

Religion might matter less in the Jakarta election than one might assume and, for many, that will be reassuring. But that does not mean that Indonesia is doing well. As this short survey experiment demonstrates, anti-Chinese sentiment is potent, and could have serious consequences beyond the election.

Notes about the Survey

The experiment was conducted as part of a larger survey related to the author’s dissertation project. The author, in cooperation with a student coordinator, trained and recruited students from a large public university in Depok to conduct the interviews. A standard quality control procedure of visiting 10 per cent and calling 20 per cent of the sample was conducted to check the validity of the interviews.