In the Kampung Akuarium neighbourhood in the north of Jakarta, a community team has been set up to increase awareness of hygiene and encourage practical social distancing measures. Photo by Dharma Diani.

Crisis, be it economic collapse, natural disaster or pandemic, deepens and amplifies the social vulnerabilities produced by inequality. Along with being the most susceptible to the health risks posed by coronavirus disease (Covid-19), the poor also often suffer the most from mitigation measures introduced to curtail its spread, as we see in the unfolding humanitarian crisis caused by a nation-wide lockdown in India.

Similarly, in Indonesia, a disproportionate burden and risk is being worn by the urban poor who, in the face of government inaction in tackling the spread of Covid-19, are having to rely on themselves and each other to survive.

In a Covid-19 update on 27 March, national government coronavirus spokesperson Achmad Yurianto said that “the rich should take care of the poor so they can live without hardship, whereas the poor can look out for the rich by not infecting them with the virus”. Despite later backtracking after widespread criticism, he nonetheless articulated a long-held paternalistic view of the poor and their communities as sources of disease, contagion and threat.

Jakarta, home to one-fifth of Indonesia’s urban population, has emerged as Indonesia’s Covid-19 epicentre with, at the time of writing, 1810 confirmed cases and 156 deaths, with the national total at 3512 cases and 306 deaths. There is strong evidence that the true number is far greater.

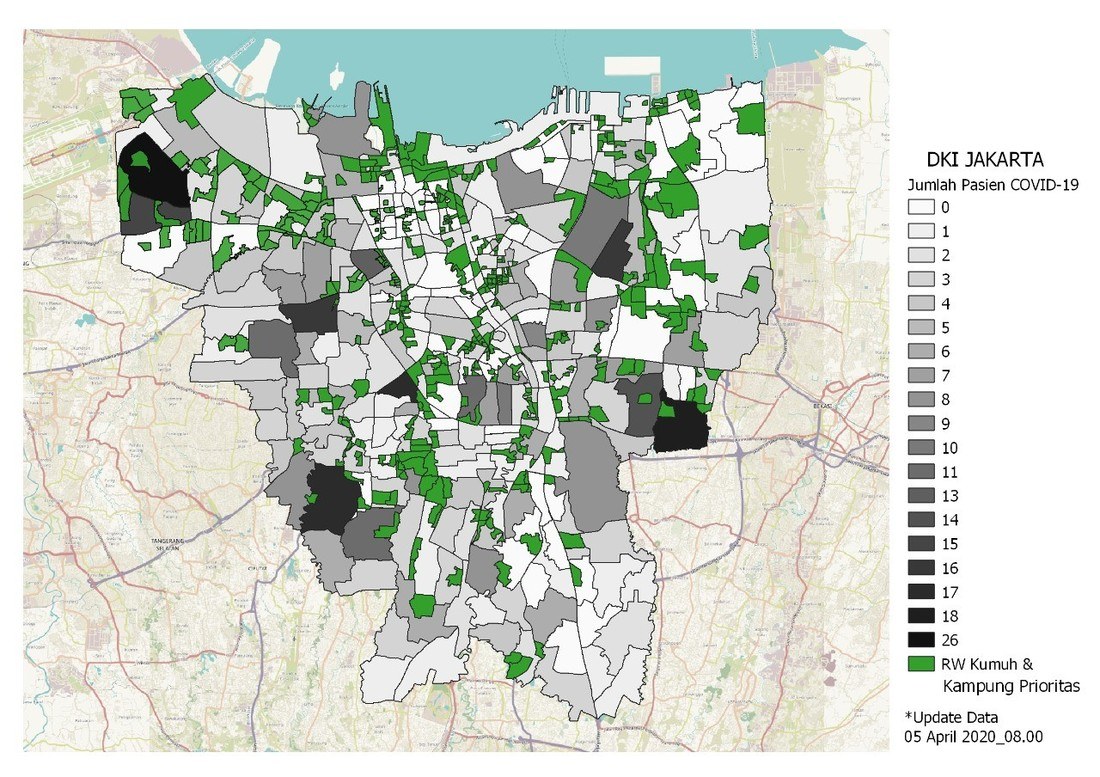

A spatial analysis of the distribution of cases in Jakarta by the Rujak Centre for Urban Studies found that, to date, only a small number of Jakarta’s poor neighbourhoods have had high numbers of infections. Mirroring trends seen in cities such as Sydney, Melbourne and Los Angeles, the largest infection clusters have been in middle-class and affluent areas.

Distribution of coronavirus cases and Jakarta “slum” neighbourhoods (in green). Image by Rujak.

It’s likely this reflects Indonesia’s extremely low levels of testing and disparity of access. But it is also possible the poor’s relative lack of social mobility may be slowing the introduction and spread of Covid-19 compared to Jakarta’s highly mobile middle class, many of whom were, until recently, enjoying heavily discounted airfares to domestic tourist destinations. Even if this is the case, however, the effect will be temporary.

Despite excruciating government delays in taking decisive action and dire predictions of a looming public health disaster, the Rujak Centre analysis suggests opportunities remain to protect the city’s most vulnerable communities.

To be effective, public health measures need to be sensitive to socio-economic and cultural context. This requires recognising that exposure to risks and the availability of resources and opportunities are unequally distributed and shaping interventions accordingly.

Core infection mitigation strategies such as increased handwashing, social distancing and staying at home in self-isolation all present significant challenges for the lived realities of Jakarta’s poor, compounded by a lack of adequate government support.

Many poor neighbourhoods, such as in Muara Angke in Jakarta’s north, have limited access to clean water and sanitation. Residents rely on buying water from vendors, which is logistically and financially difficult in times of economic downturn. Calls by urban poor activists for government to supply emergency hand-washing stations have so far gone unanswered.

Appeals for greater social distancing clash with the reality that 40% of Jakarta’s residents live in densely populated urban villages, or kampung, where the average home size is 9m2. Many of these are classified as ‘slums’ (kawasan kumuh) where housing and public infrastructure is often substandard. Residents often share cooking and washing facilities and communal space, making distancing of the kind encouraged, or necessary, almost impossible.

By contrast, luxury hotel group Aryaduta are offering corporate ‘self-isolation’ packages, in collaboration with a Jakarta private hospital, which will provide high accuracy PCR testing for any customers displaying symptoms.

Since a state of emergency was declared by Jakarta’s governor Anies Baswedan on 20 March, residents have been urged to not leave their homes, “except for urgent and essential matters such as food and health care”.

This and the recently approved further ‘large-scale social restrictions’ (PSBB) limiting social gatherings and movement throughout the city is unsurprisingly, having devastating impacts on the hundreds of thousands of the poor who make a living from the informal street economy. Under the restrictions, which will last until 24 April, public transport is reduced and schools, offices, and many shopping centres shut. Places of worship are closed, and public gatherings of more than five people prohibited. Quiet streets have left many with no income, and with no savings to fall back on. This is particularly so for owners of street food stalls, who aside from facing an inability to operate, now have difficulties in buying produce due to neighbourhood lockdowns.

The national government and city administration have announced cash and staple food assistance packages. Distribution of food staples, cloth masks and soap has begun, with plans to cover all subdistricts in Jakarta over the coming weeks. Confusion has emerged, however, over who will or won’t receive assistance. As many of the city’s poorest are not registered as Jakarta residents, they may be denied access, along with those recently thrown into poverty who are not registered as a social assistance recipient. Community activists have also expressed concern that the amount of food distributed is barely enough to last most families for one week.

When basic survival is at stake, risks must be taken. According to community activists, despite calls to stay at home, vendors and labourers are venturing further afield in search of customers or work. Loan sharks are also capitalising on the needs of the poor for quick cash, adding to what are often already crippling debts.

The rapid unravelling of what was already a precarious life in the capital leaves many with little choice other than to return to hometowns and villages across the country, with at least some likely bringing the virus with them.

According to Gugun Muhammad, an activist with the urban poor organisation Jaringan Rakyat Miskin Kota (JRMK), perceptions of the risk posed by Covid-19 among poor neighbourhoods in Jakarta has been varied. “Some are afraid and are doing whatever they can to avoid getting infected, while others are downplaying the risk and just carrying on as usual,” he said.

Many recognise the danger the virus poses but have little choice but to continue working in the streets. As one resident from Kampung Akuarium in Jakarta’s north bluntly put it, “staying at home means no money, which means we don’t eat”.

Faced with government inaction and the combined threats of disease and economic ruin, networks of mutual support and self-organisation in and between kampung are being mobilised to provide support and protection.

Social distancing has been translated at a community level in self-organised kampung-level lockdowns. Drawing on existing community defence practices deployed in times of social unrest, neighbourhoods, such as Tanah Merah, have implemented localised forms of ‘martial law’.

Locals working outside the neighbourhood can come and go through guarded portals, where disinfectant is provided. But access by outsiders is subject to vetting and hygiene protocols, with only those with essential business allowed in.

In Kampung Akuarium, a community team has been set up to increase awareness of neighbourhood hygiene and encourage practical social distancing measures. This has included asking residents to reconsider returning to their villages at the end of Ramadan, or mudik, to protect their hometowns from infection risk. Donations of isopropyl alcohol have also been used to locally produce a basic hand sanitiser, which has then been distributed among Akuarium residents, local mosques and neighbouring communities. A neighbourhood logistics team is doing coordinated shopping runs, minimising the number of residents who have to travel often long distances to produce markets.

The JRMK has been active in sourcing and distributing information and resources among its network of poor neighbourhoods and informal sector communities.

With great anxiety in many poor kampung over access to food, through its solidarity networks with farmers in East and Central Java, the organisation has purchased rice to distribute through its network of kampung and poor communities. Traditional and affordable herbal drinks, believed to boost immunity, have been brought in from Yogyakarta.

JRMK is also crowd-funding to provide financial relief for street vendors, day laborers, becak pedicab drivers and other informal sector workers. More than 200 families have already been provided with funds, accepted on the promise that they will stay at home.

Jakarta’s poor are, by necessity, resilient, resourceful and pragmatic. Many accept the significant risk presented by Covid-19 and are taking practical action with limited resources to prevent its spread, while trying to stay economically afloat.

However, as social and economic opportunities shrink even further as the impacts of social distancing and shutdowns take hold, self-help networks alone will not be enough.

Substantive government intervention is needed immediately to enable Indonesia’s poor to get through this crisis. Unless all of the poor are offered rapid testing, sufficient and ongoing food staples, cash subsidies free of red-tape, basic infrastructure like clean water supplies and moratoriums on evictions and debt repayments, they will suffer the greatest impacts of coronavirus.