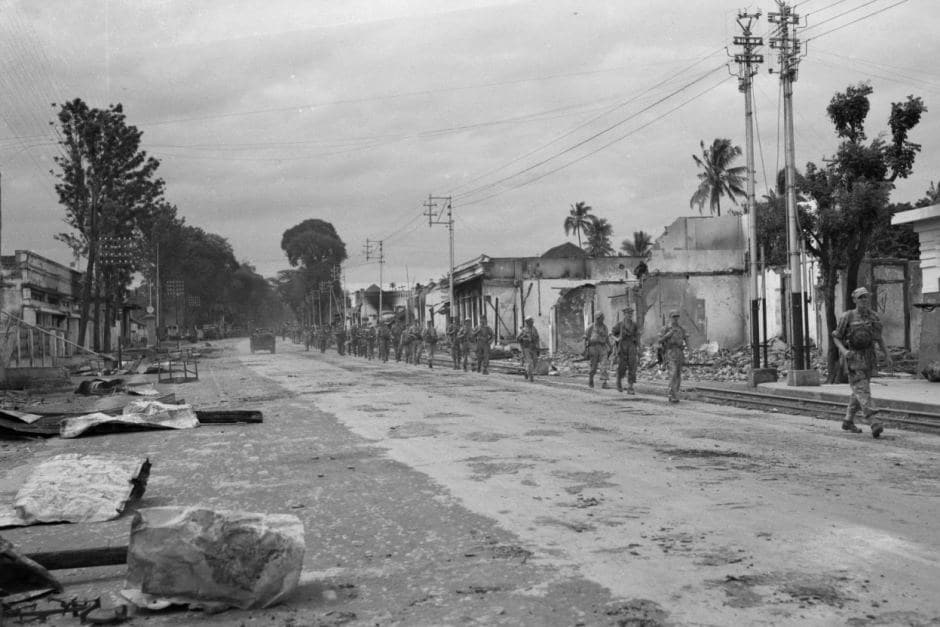

From 1945-1949, Dutch troops fought against pro-independence Indonesian forces, resulting in 150,000 Indonesian and 5,000 Dutch deaths. Photo from Dutch National Archives.

This year marks 70 years since the official end of Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia. While they were in charge, Dutch forces perpetrated egregious human rights violations against Indonesians, including mass killings of civilians.

Unlike many European and Asian colonial powers, Dutch governments have apologised and provided compensation to some families of victims massacred by Dutch forces.

Despite this, successive Dutch governments have been largely unwilling to address human rights abuses perpetrated by Dutch forces in Indonesia unless ordered to by courts and, at times, have sought to impede access to justice for Indonesian victims and their families.

In 1945, following the capitulation of Japanese occupying forces and Indonesia’s proclamation of independence, the Dutch attempted to regain control of Indonesia. From 1945-1949, Dutch troops fought against pro-independence Indonesian forces, resulting in 150,000 Indonesian and 5,000 Dutch deaths.

In 1947, Dutch troops entered the village of Rawagede (now Balongsari) in West Java to quash Indonesian pro-independence forces, executing between 150 and 431 male civilians. Sixty-four years later, the Dutch government apologised for the Rawagede tragedy. Importantly, the apology was conducted in Balongsari by the Dutch Ambassador to Indonesia, Tjeerd de Zwaan, in Indonesian and English. In 2011, the Dutch government paid US$26,560 each to nine of the victims’ widows. Since 2011, at least 40 other widows have also received €20,000 in compensation from the Dutch state.

Over about three months from late 1946 into early 1947, Dutch troops led by Captain Raymond Westerling killed thousands of civilians in South Sulawesi in an attempt to quash opposition to Dutch rule. In 2013, Ambassador de Zwaan apologised for the Westerling massacres and the Dutch government issued a written apology. The same year, the government provided US$27,000 to 10 of these victims’ widows.

These apologies and compensation are undoubtedly significant, particularly given that no individuals have ever been prosecuted for their involvement in the Rawagede or South Sulawesi killings.

However, the potency of these apologies and compensation is limited by the fact that they were not provided by the Dutch government of its own volition. Rather, the apology and compensation for the Rawagede tragedy were ordered by Dutch courts following a group of victims’ widows filing a lawsuit against the Dutch state. Similarly, the apology for the Westerling massacres followed 10 victims’ widows suing the Dutch state and requesting an apology. The compensation provided to these victims’ widows was also ordered by a Dutch court.

Further, the specific and partial nature of the Rawagede and South Sulawasi apologies is problematic as they suggest that these killings constitute a “single black page in an otherwise white book” of Dutch colonial history. But this is not the case. These killings are not aberrations. They are representative of a pattern of human rights violations perpetrated by Dutch colonial forces in Indonesia before 1945 and from 1945-1949. For example, in 1904, Dutch forces were responsible for the killings of 5621 Indonesian civilians in the village of Kuta Rih. Other human rights violations against Indonesians during Dutch rule include the imprisonment of thousands of pro-independence Indonesians, including Soekarno.

The extent to which the apology and compensation for the Rawagede tragedy demonstrate Dutch remorse is questionable as the Dutch state attempted to quash the lawsuit filed against it by invoking the statute of limitations, which the court rejected. The judges deemed that “the [Dutch] state acted wrongly through these executions.”

Since the Rawagede apology and compensation, Dutch governments have repeatedly attempted to avoid paying compensation to Indonesian victims of human rights violations perpetrated by the Dutch in the 1940s and their families by invoking the statute of limitations or appealing Dutch court orders.

These actions indicate that the Netherlands government remains largely unwilling to address human rights abuses perpetrated during its colonial rule over Indonesia. This is also demonstrated by the fact that no Dutch government has apologised for the other human rights violations perpetrated during Dutch rule in Indonesia.

Similarly, no Dutch government has apologised for the invasion and colonisation of Indonesia. This inaction is significant as it suggests that Dutch governments lack remorse for Dutch colonialism and the racism which underpinned it and is likely motivated by Dutch governments fearing large-scale compensation cases.

In 2012, not long after the Rawagede apology, three research institutions in the Netherlands called for a large-scale investigation into Dutch military operations during the 1945-49 Dutch-Indonesian conflict. The Dutch government initially refused to fund the study. But four years later, it agreed to provide over €4 million in funding for the investigation.

Although some Indonesian historians are involved in the project, other Indonesian historians and activists have condemned the investigation and questioned its impartiality, suggesting that it will attempt to present a watered-down narrative of colonial history. The project is due to be completed by 2021 and the Dutch government has insisted that researchers will have complete independence. Given the government’s track record, it is understandable that academics and activists question its willingness to support a more complete and impartial account of the abuses committed by Dutch forces.

Earlier this year, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte met with President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo in Jakarta. The two leaders did not discuss colonial era human rights violations or the Dutch colonisation of Indonesia. Rutte’s government is undoubtedly seeking to avoid more compensation cases and Jokowi is likely avoiding antagonising the Netherlands, which is the seventh largest investor in Indonesia.

In 2016, Rutte asserted that “the Netherlands places a high value on protecting and promoting human rights.” Given Rutte’s government’s action or, more often, inaction, in relation to colonial era human rights abuses in Indonesia, his rhetoric does not match reality.