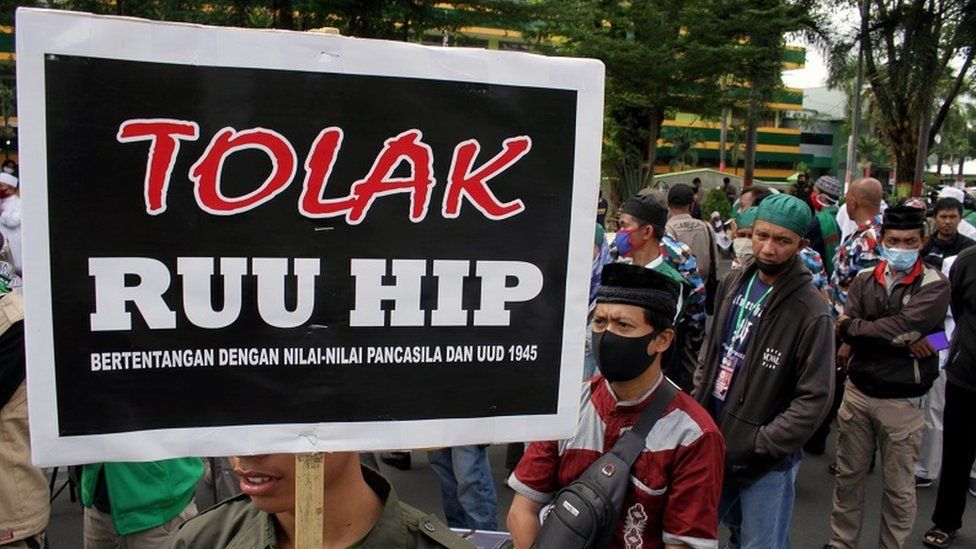

Islamists, as well as mainstream Muslim organisations like Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama, rejected the bill in its original form for its supposed weakening of Pancasila’s first pillar: belief in one God. Photo by Antara.

As Indonesia’s health care system, bureaucracy and economy was being buffeted by the Covid-19 pandemic over the last few weeks, a debate was also raging for the legal heart of the Indonesian state. It wasn’t about an economic stimulus bill or the Covid-19 response but rather a new bill on the state ideology, the “Pancasila Guidelines Bill” (RUU HIP, Haluan Ideologi Pancasila). It sparked controversy immediately.

The bill has foundered over the last week. This legislative drama was a major set-back for President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), the party with the largest proportion of seats in the legislature. Was the bill’s failure a sign of other parties working to derail PDI-P’s legislative agenda? Or did it represent a reinforcement of Indonesia’s carefully balanced constitutional equilibrium?

To understand Pancasila, it is necessary to understand its political and legal purpose. Pancasila is embedded in the Preamble to the 1945 Constitution, providing a set of principles intended to act as the foundation for all Indonesian laws. Its five pillars are: belief in one God, humanitarianism, national unity, representative democracy, and social justice. These are a pragmatic compromise between secularism and religiosity.

Pancasila is narrated in an abstract way, and its strategically ambiguous drafting can accommodate Indonesia’s ethnic and religious diversity. However, if abused for political purposes, it can also be used to politically attack almost any opposition group as ‘anti-Pancasila’ – as happened often enough under Soeharto’s New Order regime, when the only valid interpretation of the state ideology was that fixed by the government.

Previously Jokowi’s administration had established the Agency for Pancasila Ideological Education (BPIP). PDI-P chair and former President Megawati Soekarnoputri serves as the head of its steering committee. The proposed bill would have helped to strengthen the functions of this agency, but it also aimed to regulate the values of the Pancasila ideology in a clear and legalistic way.

For this reason, the public, Muslims groups and some elements of the military criticised the bill heavily. One of its opponents, the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), said the bill would allow for the repression of Muslim groups, as happened under the New Order.

Likewise, the influential Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI) threatened to call its supporters out onto the streets if the government did not stop deliberation of the bill. The MUI was concerned that the bill was somehow a sneaky way of allowing the banned Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) to be revived. This was a baseless presumption, but the ghosts of PKI have a real resonance in the Indonesian body politic.

Muhammadiyah, the modernist Islamic organisation, also issued a strong statement rejecting the bill. It argued that a formalising Pancasila in this way was redundant given the public was already well aware of the tenets of the national ideology.

Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), was particularly critical of Article 7 of the bill, which stipulates the “trisila” (three principles) concept as the basic tenet of Pancasila: socio-nationalism, socio-democracy and cultural divinity. According to the bill, these three values can be crystallised in a single “ekasila” of mutual cooperation (gotong royong). NU, MUI and Muhammadiyah rejected this crystallisation because it “removed” the first pillar: belief in one God.

The trisila/ekasila concept is based on a famous speech by Indonesia’s first president, Soekarno, during the constitutional debates of June 1945. The historical context is important, but if these ideas were inserted as a legal norm in the bill, it could open a Pandora’s box of diverging political ideas and priorities.

On 16 June, Vice President Ma’ruf Amin and Coordinating Minister of Politics, Security and Legal Affairs Mahfud MD met with the leaders of MUI, Muhammadiyah and NU. The government agreed to postpone deliberation of the bill, and said it would focus on handling the Covid-19 pandemic.

After the meeting, PDI-P indicated that it was willing to compromise and remove Article 7 on the crystallisation of Pancasila’s five pillars and add an article affirming the banning of communism. But a problem remains: will the bill allow the government to promote a singular, restrictive interpretation of Pancasila?

Just before the national legislature went into recess, the Jokowi administration sought to reorient the bill and focus it on strengthening the role of the BPIP. The next stage of legislative deliberations will therefore see debate over the authority of this Pancasila education agency and what sort of role it will play. Will BPIP allow Pancasila to remain an open, inclusive constitutional vision or will it again be used as a prescriptive, repressive tool? It may be a cliché, but in this instance it is appropriate: the devil will be in the detail.

From one angle, the move to delay deliberation of the bill could be seen as major backwards step for Jokowi and PDI-P leader Megawati. It could also be seen as a win for the scare campaign religious organisations ran against “communist influences”. This led to demonstrations in which PDI-P’s flag was burnt.

Even putting aside political squabbles and the dragging up of old ghosts like fear of communism, this bill does present real problems. Soekarno ensured Pancasila was drafted with broad conceptual strokes rather than specificity. He actively avoided referring to any group or religion in the wording of the five principles. By taking the more legalistic approach to Pancasila the bill proposes, the ambiguity that provides Indonesia with “unity in diversity” could be shattered. Political machinations could see one group or another seeking to make Indonesia’s identity reflective of them.

Groups could claim that they were more “Pancasilaist” than other ethnicities, religions or political groups. Or even more ominously, the government could easily label its political opponents as anti-Pancasila, essentially making them enemies of the state.

To have an “imagined community” in a polyglot nation like Indonesia, legal and political boundaries must be fluid enough to capture an eclectic array of religious and ethnic identities.

Even though this legislative saga may appear to have the makings of a failure, that is not necessarily a bad thing. It may ensure the idea of the Republic of Indonesia remains strategically ambiguous – as Soekarno always intended – and that should matter a lot to every minority in the country.