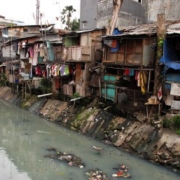

Some 243 residents filed a class action against Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan over the flooding that affected Jakarta in early January. Photo by Risky Andrianto for Antara.

Since December 2019, heavy rain has fallen across many Indonesian provinces. The combined effects of climate change, abominable urban planning, poor waste management, inadequate human preparedness, and longstanding oligarchic influence over development have meant that floods and landslides are unavoidable during the rainy season.

In Jakarta, flooding is a major political issue. Before every election, candidates promise to tackle flooding. Once they are elected, they are scrutinised and attacked over every move they make to meet these promises.

The issue has been aggravated further by unresolved tensions resulting from the deeply polarised 2017 Jakarta Gubernatorial Election and the Presidential Elections that fell either side of it in 2014 and 2019. Deep divisions between supporters and opponents of Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan have created a toxic environment on social media. Both sides have peddled misinformation and hoaxes, making it even harder for residents to distinguish objective analysis from fiction.

The heated social media debate should not overshadow the fact that residents have suffered deeply from these floods. During the worst flooding at the start of January, at least 67 people died, and hundreds of thousands were displaced. Flood waters damaged not just citizens’ houses, but also public facilities. Schools and hospitals could not function. Electricity was switched off in 724 locations, further disrupting citizens’ activities. Financial losses were estimated to be more than Rp 10 trillion (A$1.1 billion).

Some citizens turned to social media to call for evacuation support, after they couldn’t get through to government crisis centres. Many of those requesting support were seniors who had mobility difficulties. Others used social media to try to find missing family members. Mothers raised concerns about how the flooding and blackouts had destroyed their frozen milk.

These data and compelling stories seem strong enough to prove that residents suffered significant losses. But who is to blame? Who should be responsible for providing residents with compensation or leading recovery efforts? For some residents, at least, the buck should stop with Jakarta Governor Anies.

On 13 January, 243 residents filed a class action against him. The plaintiffs claimed that the city government had not conducted regular cleaning over waterways, no rubber boats were made available for evacuation, and the government had failed to provide residents with sufficient information about flooding. They are asking for Rp 42 billion in compensation.

The Central Jakarta District Court was scheduled to hold the first hearing on 3 February. This hearing was to review whether formal administrative requirements had been met and hear from five residents, representing each of the city’s municipal areas.

But the hearing was delayed. Worryingly, three of the representatives failed to turn up. Their lawyer said they had been intimidated and urged to withdraw their complaint. These allegations are yet to be proven, but there is no doubt the class action has triggered pushback.

The Gerindra political party, which supports Anies, said that the lawsuit should have been directed at President Joko Widodo. Gerindra lawmaker in the Jakarta Regional Legislative Council (DPRD) Purwanto said that the losses resulting from the Jakarta floods were not as severe as in other cities, and should be used as an opportunity for learning, rather than as a tool to attack the governor.

On social media, these kinds of statements are quickly reduced to partisan mudslinging. Those who raise concerns about Anies’s performance are typically dismissed as “tadpoles” (referring to supporters of President Jokowi or previous Governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama). Those who direct their criticism toward Jokowi are derided as “bats” (referring to supporters of Prabowo Subianto or Anies).

This will not be an easy case for the court. The details of the case are relatively straightforward, but the politics of flooding mean that the result is likely to be seen as partisan – whatever the court’s decision. To prove civil liability, the presiding judges will likely refer to Article 1365 of the Civil Code. This states that any person who causes damage and/or loss to another party by means of an unlawful act must, because of his or her fault in causing the loss, compensate for that loss.

On 17 February, the court will complete the formal examination of the plaintiffs’ case. Both parties will be given the opportunity to present their documents. On 3 February, the plaintiffs were given two weeks to replace their three missing representatives (or convince the original representatives to turn up). If the presiding judges decide that the formal requirements of a class action suit have been fulfilled, the next trial sessions will focus on proving whether the governor committed an “unlawful act” and whether there is causality between the act and the victims’ damages and losses.

The Civil Code does not provide much clarity on how one determines whether an act was “unlawful”. A narrow interpretation of the provision might be to consider an act unlawful only if it breaches written laws or regulations. However, legal academic Rosa Agustina has argued for a broader interpretation, saying an act should be considered unlawful if the perpetrator has failed to meet legal obligations, it violates the victim’s rights, or it breaches principles of propriety, accuracy, and prudency.

Another legal academic, Koerniatmo, meanwhile, has argued for an even broader reading, saying that in the case of flooding, courts must also consider “the community’s sense of justice”. This reflects the fact that taking the governor to court should be seen as a public act by citizens to exercise their rights and to hold the government to account. It should not be dismissed just as a strategic move by political players with an axe to grind.

It is important that the court must examine and decide the case on its merits. The result won’t just affect the plaintiffs – it will have significant implications for the wider Jakarta population. No matter what the court decides, they will still have to endure more floods of increasing severity in the years ahead.