Several of the bills that were the target of student protests in 2019 have been included on the 2020 Prolegnas. Photo by Aditya Pradana Putra for Antara.

The House of Representatives (DPR) published in January its list of priority bills (National Legislative Program, Prolegnas) for 2020.

It says it plans to deliberate 54 bills in this year’s legislative sitting period, and they include four worrying: “carry-over bills” from the previous DPR term (2014-2019): the revised criminal code bill (RKUHP or RUU KUHP), amendments to the 1995 Law on Corrections, amendments to the 2009 Law on Mineral and Coal Mining, and amendments to the 1985 Law on Customs and Duty.

Deliberations on three of these carry-over bills were halted after massive student rallies in September 2019. Students criticised the bill on corrections because it would have softened parole requirements for corruption convicts. They rejected the mining bill for being too pro-company and neglecting the rights of mining-affected communities. But arguably the loudest student and civil society protests related to the criminal code bill, which threatens basic rights, such as freedom of expression, while weakening law enforcement against human rights violations and corruption.

Although the DPR claimed debate on these bills was concluded in the last DPR term, their carry-over into the new term will provide new opportunities to listen to and accommodate stakeholders’ criticisms before passing the controversial bills into law. It is vital that the DPR does so.

One of the main reasons protests were so heated in 2019 was the fact that deliberation on these bills was done with only very limited opportunities for contributions from civil society and the public. In the case of the RKUHP, for example, a number of its provisions were closely related to public health, corrections and development planning, but no civil society groups, practitioners or academics working in these sectors were ever consulted.

The public has the right to participate in all stages of legislative drafting, especially in the planning and deliberation phases. Article 96 of Law No. 12 of 2011 on Lawmaking states that to facilitate the public’s right to participate in the lawmaking process, all draft bills should be made open and accessible. At the very least, the DPR must update its website to disseminate all bills listed on the Prolegnas.

It is significant that the government only designated four bills as carry-over bills, even though several others, including the anti-sexual violence bill, were discussed in the previous term. Because the anti-sexual violence bill has not been included in the carry-over list, legislators will have to re-start the deliberation process from the beginning, meaning the chances of it being passed this year are slim.

Another very contentious bill listed on the priority list is the cybersecurity bill. Several provisions of the bill potentially violate the right to privacy and freedom of expression. Some analysts have even expressed fears that the bill will provide the State Cyber and Cryptography Agency (BSSN) with sweeping powers that could rival the State Intelligence Agency (BIN).

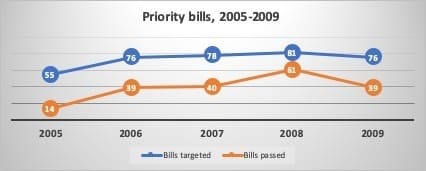

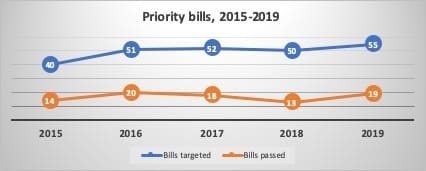

In terms of quantity, the target of 54 bills is unrealistic. Over the last five years, the DPR and government have only been able to pass an average of 15 to 16 bills each year. During this time, they also prepared targets of between 40 to 55 priority bills each year. The fact that the problem has been the same every year shows that neither the DPR nor the government think there is anything wrong. Given that the DPR never manages to reach even 50 per cent of its target, it is no surprise that the public considers the DPR and government’s performance in producing laws to be poor.

In addition to the annual target, the Prolegnas also includes a long list that the DPR and government aim to pass over the five-year term. The DPR and government have also put 248 bills on their long list, on top of the 54 bills listed for this year. The Indonesian Centre for Law and Policy Studies (PSHK) has noted that over the last three terms, the DPR and government have continually set unrealistic targets for the long list, just as they do for the annual list.

In fact, the Prolegnas is really just a wish list for the DPR and government (as well as the Regional Representatives Council (DPD), which also has the right to propose bills), rather than a serious plan. Any progress at all towards their targets is considered success.

Bills targeted and passed into law each year, 2005 to 2019 (from Fajri Nursyamsi and other references compiled by PSHK)

This needs to change. The Prolegnas needs to become what it was intended to be: a document used to direct and manage the legislature.

At the beginning of each legislative term, the government, DPR and DPD should discuss plans for legislative reform over the next five years. According to Article 95A of Law No. 12 of 2011 (as revised in 2019), the DPR, DPD and government should evaluate the efficacy of existing laws, and use this evaluation to plan the next Prolegnas. This would help ensure that the proposed bills on the Prolegnas are truly derived from the consensus of the three institutions and are based on the actual needs of the public. It will also discourage the DPR and government from setting ambitious and unachievable targets.

The lack of considered planning is evident in the poor quality of bills on the 2020 Prolegnas. Several bills potentially contradict each other or conflict with existing regulations. The divisive bill on family resilience (RUU Ketahanan Keluarga), for example, contradicts provisions in the anti-sexual violence bill, not to mention other human rights and constitutional provisions. The family resilience bill introduces seriously questionable provisions that would discriminate against women and sexual and gender minorities, while the anti-sexual violence bill aims to achieve more or less the opposite, and protect all Indonesians (no matter their gender or sexual orientation) from violent acts.

There are several other bills of questionable urgency. The proposed bill on protection of religious leaders and religious symbols is one such bill. The protection of citizens (of all professions) is already covered by existing laws, such as the Criminal Code (KUHP) and Law No. 39 of 1999 on Human Rights.

Another case is the proposed amendments to the 2013 Law on Medical Education. The 2013 law should have never been passed in the first place, given that there is another law regulating this topic, the 2012 Law on Higher Education. Medical education could have been sufficiently regulated by subordinate regulation under the 2012 Law, using for example, a government regulation (peraturan pemerintah), presidential regulation (peraturan presiden), or ministerial regulation (peraturan menteri), in line with the provisions of Law No. 12 of 2011 on Lawmaking.

Another major controversial element of this year’s list of priority bills is the four “omnibus” bills. Of the four, the bills on job creation, taxation and the national capital were initiated by the government, while the bill on pharmaceuticals was proposed by DPR. The job creation bill has attracted the most public and media attention over the past month. Academics and civil society organisations have complained that the drafting process was carried out by the government behind closed doors. The only stakeholders involved were representatives of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce. But as an “omnibus” bill, it affects many sectors, such as labour, land and environment, media and more. Many more stakeholders should have been involved in the drafting process – trade unions and journalists, for example.

In addition to this opaque drafting process, several provisions also have the potential to reduce public rights and threaten environmental sustainability. In the circulated draft bill, there are provisions that weaken environmental impact analysis (AMDAL) requirements from law to subordinate regulations. The bill certainly seems to de-emphasise public participation from something that should be clearly regulated in the relevant law to merely an administrative issue covered by subordinate regulations.

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has emphasised that these omnibus bills were intended to revise a number of laws at once in a short time. At the annual meeting of the financial services industry in January, Jokowi even stated that he would appreciate it if the DPR could complete the discussion of the job creation and taxation omnibus bills within 100 days.

Ominously, he also instructed the National Police chief, the head of BIN and the Attorney General to “approach and communicate” with “organisations” who criticised the government’s plan for the omnibus bills. He did not specify which organisations he had in mind. But trade unions, civil society organisations and academics have been the omnibus bills’ fiercest critics.

Policymaking in the 2019-2024 legislative period is still at a very early stage. But there are already major problems that need to be addressed as soon as possible, both on the government and DPR sides.

The DPR has to conduct an evaluation of the Prolegnas at the end of this year. It should use this opportunity to more realistically map and identify which bills are the most pressing and realistic to be deliberated during next year and the rest of the 2020-2024 term. In the future, the DPR needs to completely reconstruct its Prolegnas planning process, so that the Prolegnas is not just a wish list, but a set of practical, achievable guidelines for legislative policy reform.

As discussions on the omnibus bills heat up, the DPR must also conduct deliberations transparently and ensure that all important stakeholders—especially the most affected groups—are involved. The DPR should not repeat the mistakes of the government in conducting the drafting process behind closed doors.

While this notion might seem foreign to Jokowi, it is, in fact, quite possible to pay attention to infrastructure development, human resource development, protection of human rights and environmental preservation at the same time.