‘Women, don’t be afraid to participate in politics!’ Activists and politicians mark International Women’s Day in Banda Aceh in March. Photo by Irwansyah Putra for Antara.

The race between Joko Widodo and Prabowo Subianto might have captured most of the media attention, but tomorrow nearly 8,000 candidates will also be competing for 575 seats in the national legislature (DPR). About 40 per cent of these candidates are women, the highest proportion of female candidates ever. But what do the numbers really tell us about women’s representation in Indonesian politics?

Indonesia first introduced affirmative action for gender justice through Law 31 of 2002 on Political Parties, which required political parties to “consider gender equality and equity” in the recruitment of legislative candidates and in political party structures from the national to the local level. After two rounds of revisions, in 2008 and 2011, the phrase “consider gender equality and equity” was strengthened to “include 30 per cent representation by women”.

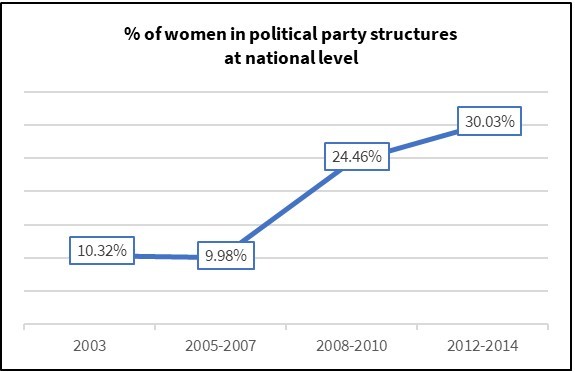

While there were no sanctions for parties that ignored the 30 per cent rule, women’s representation in political party structures increased from 2003 to 2014, according to analysis by Cakra Wikara Indonesia (CWI). In 2014, two political parties even exceeded the 30 per cent threshold in their organisational structures: the Democratic Party and Hanura.

Source: Ministry of Law and Human Rights data

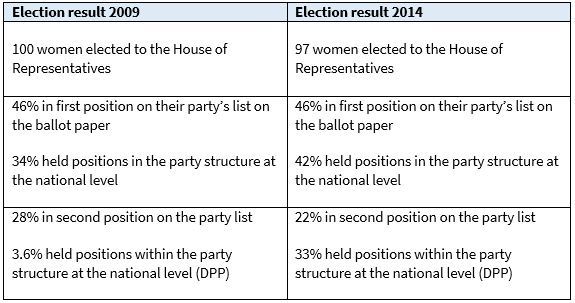

The past two elections, in 2009 and 2014, saw mixed results for women’s representation. Although the total number of female candidates elected to the House of Representatives (DPR) dipped slightly from 2009 (18 per cent) to 2014 (17 per cent), the proportion of successful candidates who also held structural positions increased. From the 100 women elected to the DPR in 2009, 15 per cent were from political party structures at the national level (that is, in central leadership boards, or DPP). From the 97 women elected in 2014, meanwhile, as many as 28 per cent held these roles.

Source: General Elections Commission (KPU) data

In 2014, the General Elections Commission (KPU) issued a regulation (No. 7 of 2013) requiring new parties (and existing parties that did not reach the legislative threshold in the previous elections) to meet the 30 per cent quota or they would not be allowed to participate in the elections. There was no such requirement in 2009. In the lead-up to the 2019 elections, enforcement has been further strengthened by the introduction of sanctions under KPU Regulation No. 6 of 2018, which bans the participation of all parties that do not have at least 30 per cent representation by women in party structures at the national level.

The 2014 elections saw growing numbers of women holding positions in party structures at the national level being put forward in the first and second position on ballot papers. Since 2009, Indonesia has used an “open list” system, meaning that electors are able to vote for individuals, rather than simply voting for a party. This also forces legislative candidates from the same party compete against one another for votes.

Despite the open list system, candidates higher on the party list are more likely to be elected. In the last two elections, 65 per cent of successful legislative candidates were from the first position on party lists, while 19 per cent were from the second position. These positions therefore tend to be filled by high-profile candidates considered to have a strong chance of winning, such as incumbents, local elites, or those with close links to elites, such as wives, children or siblings, or others with ties to centres of power in party structures.

Women from political party structures should be the first choice for these strategic positions on the ballot paper, because these women usually have years of experience in networking and organisational and program management. Some of them have even worked as activists. Their skills in managing relationships with their political base makes them better prepared to occupy positions in the legislature.

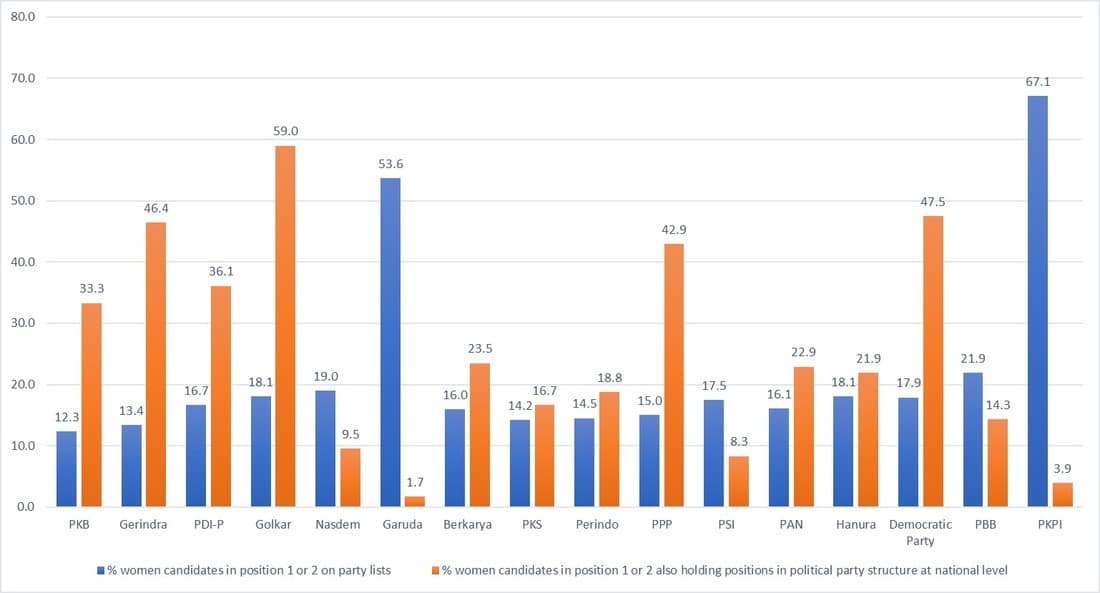

In the 2019 elections, 603 female legislative candidates are competing in position 1 or 2 on party lists. As many as 19 per cent of these women hold positions in party structures at the national level, according to KPU data.

The following graph illustrates the percentage of women candidates nominated in the first or second position in the 2019 elections and the proportion of these women who also hold structural positions in their parties at the national level.

Source: KPU

For almost all parties competing in the 2019 elections, the percentage of women offered the first or second position on the ballot paper is less than 20 per cent. The small Garuda Party and Indonesian Justice and Unity Party (PKPI) do better on this measure because in many electorates they are only putting forward one or two candidates.

In terms of representation in party structures, almost half of the women placed in position 1 or 2 from the Democratic Party, Gerindra and the United Development Party (PPP), are also members of their party structure at the national level. For Golkar, the figure is nearly 60 per cent. Garuda, PKPI and Nasdem have the smallest proportion of women from party structures at the top of their lists. This could reflect the more streamlined nature of the newer parties’ structures, in which smaller numbers of both men and women hold positions of power, compared to the older parties. But it could also reflect the fact that many parties turn to a less than ideal pool of women to fill the top positions on the ballot paper, such as public figures or local elites (or those with ties to local elites).

If more women held strategic positions in party structures, then the number of women at the top of the party list is likely to be higher. Those with strategic positions within political parties, like leader, secretary general, treasurer or heads of recruitment, tend to have greater influence on strategic decisions within party structures. Research in Mexico and Chile, for example, has shown that if recruitment in political parties is carried out by women, then there are more opportunities for selection of other women. In Indonesia, since 2003, only 11 women from eight parties have held, or currently hold, these strategic positions. This helps to explain why so few women are placed at the top of the party lists.

Women face a number of obstacles in reaching positions of power within parties. One woman said it took her 10 years of hard work to reach the position of deputy secretary general in her party’s national leadership board. Her commitment as a party member was under constant scrutiny, and she was required to consistently demonstrate active participation in party events.

With political party structures dominated by men, most parties still have highly masculine organisational cultures. Women must adapt themselves to these conditions “whether they like it or not”, our source said. Women also struggle to participate in some strategic activities in the party because of the double burden they carry with their responsibilities as wives and mothers.

Women also face obstacles in relation to internal divisions within parties, when women are forced to choose among elite factions. Following splits, members who are aligned with the winning faction tend to be retained in party structures. Women are generally more reluctant to take sides when a party split occurs, and as such, they tend to be overlooked for promotion following splits.

A further problem is that as yet, no party has designed internal policies and programs to hone women’s political skills. Although some parties have programs to strengthen women’s capacity, they are mostly limited to training for the purposes of winning elections. Research has shown that political parties see the 30 per cent quota as simply an administrative requirement. They do not consider the capacity and potential of women, who could help them to achieve a larger objective, transformation of policy making to tackle gender inequality.

Going forward, it is important to push for greater women’s representation in political party structures, especially in strategic positions. Transparent recruitment and selection mechanisms will be vital if women are to access these strategic positions. The presence of women in strategic positions can strengthen their bargaining power and increase their influence over strategic policymaking in parties. They could use this influence to increase the numbers of female legislative candidates in top positions on the ballot and in electorates considered party strongholds.

The state has made efforts to promote participation and representation by women in political parties, for example through the Elections Law, the Law on Political Parties, and KPU regulations. But increasing women’s representation in the legislature will be difficult unless political parties promote more women into powerful positions in party structures.

Sadly, few parties have shown any interest in establishing policies to empower their female members. Without political party reform, female representation is likely to continue to languish, no matter the best efforts of the regulators.