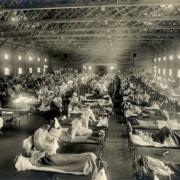

A man washes his hands at a hand-washing station in Yogyakarta. Photo by Hendra Nurdiyansyah for Antara.

Going by international coverage of the Covid-19 crisis in Indonesia, one might conclude that the country has little hope of managing the outbreak. Media have referred to the “Covid-19 disaster to our north”, and described the situation as a “catastrophe”. One ABC reporter even went so far as to suggest that Indonesia was on the verge of becoming a failed state.

A contextual and strengths-based approach is sorely needed in media reporting on Indonesia’s response to Covid-19. Constant reporting on the potential for “disaster” has failed to acknowledge that many of the factors that amplify the risks of Covid-19 for the Indonesian population are structural and therefore cannot be changed in the short term.

These risks include: the high population density in large cities and some rural areas that makes social distancing extremely difficult; the huge informal workforce who work in public spaces and on the street and who will not eat if they don’t work in these spaces; and the very large number of people who are either homeless or who live in informal urban settlements in conditions where social distancing is simply impossible.

The administrative and political structure of the nation also makes coordinating the response challenging. A response must be coordinated over 34 provinces with markedly different geographic conditions and varying health systems capacity. This has proven a major challenge in Australia with only eight state and territory governments – so obviously it’s going to be far more complex in Indonesia.

It’s true that Indonesia’s rate of testing is too low. But this is something that almost all lower and middle income countries have been struggling with – across the world, rates of testing tend to be higher in wealthier countries.

Those who report on Indonesia should be acknowledging the extent to which these contextual factors affect the nation’s ability to respond to any epidemic.

Important contributions that have been largely invisible in English language media reporting include the proactive response of Indonesian communities, health workers and religious organisations.

Many neighbourhoods have chosen to go into lockdown to slow the spread of the virus, children are home from school and childcare all over the archipelago, and those people who can work from home are doing so. Community kitchens have sprung up across the country to support those in the informal sector who have lost sources of income. A range of crowdfunding campaigns have also been launched to support vulnerable communities, like transwomen and people living with HIV.

Religious organisations have clearly backed social distancing. Early in the outbreak in Indonesia, the country’s peak clerical body, the Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI) issued a fatwa (religious ruling) promoting isolation for those exposed to Covid-19, and urging Muslims to follow the required medical protocols in relation to the preparation and burial of people who have died as a result of Covid-19. Daily sermons are now being streamed live into people’s homes and in many places mosques and churches have closed their doors.

A massive drive to re-educate and motivate people to hand wash occurred before borders closed and was happening in institutions from preschool age onwards. In informal urban settlements that lack clean water and sanitation, communities are working together to distribute sanitiser. A league of unregistered or non-practicing doctors and nurses have come forward, just as is the case in Australia, to boost the capacity of the health system and are involved in contact tracing, education, counselling and testing.

Many universities are now closed for teaching and have refocused their efforts on the Covid-19 response, contributing to ever-shifting action plans and the constant need for data on the progression of Covid-19. Universities in West Java collaborated to design a portable ventilator, which has already passed testing and is in production for distribution to hospitals facing shortages.

While criticism of the Indonesian government’s slow initial response may be warranted, it is crucial to acknowledge the strengths of the current community response and the fact that a huge proportion of people who can isolate, social distance or support the Covid-19 response, are choosing to do so.

The epidemic is likely to affect Indonesia for longer than it will high-income countries with stronger health system capacity, and in this context, the actions of communities will be crucial to limiting its impact. Acknowledging what people are doing right, and encouraging other communities to replicate successful responses, is essential for promoting the best possible outcomes.

The extraordinary resourcefulness of Indonesian communities is evident in the all too common experiences of living through and recovering from large-scale disasters such earthquakes, tsunamis, floods and volcanic eruptions.

Resilience is also a product of living in conditions where other infectious diseases such as malaria and dengue take tens of thousands of lives annually. Covid-19 and the resilience required to endure this particular epidemic should also be viewed in the context of the multiple hardships that different Indonesian communities already endure.

Balanced reporting that acknowledges both the strengths and limitations of Indonesia’s multifaceted response to Covid-19 and the structural constraints that shape the response is needed.