Under Indonesian law, Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukuamaran will be given 72 hours’ notice. Dressed in white, they will be transported together from Kerobokan Prison at night to a remote location, accompanied by a chaplain if they wish. Once they arrive, their handcuffs will be removed, their hands and legs bound, and they will be tied to a poles next to each other. They can choose whether to stand, sit or kneel for their execution, unless the prosecutor determines otherwise. They will have three minutes to “calm themselves”, again accompanied by a chaplain if they wish. They will then be offered blindfolds, and a doctor will mark the location of their heart in black on their clothes.

A firing squad of 12 officers will stand between five and 10 metres away. Only three of these 12 officers will have live bullets, the rest will have blanks. On the commander’s signal, all 12 officers will fire. If Chan and Sukumaran then still show signs of life, the commander will shoot them above the ear. If they are still not dead, this finishing shot can be repeated until the doctor decides they are dead. Afterwards, their corpses will be handed over to their families.

This will be the first time Australian citizens have been executed in Indonesia. Chan and Sukumaran appear to have finally exhausted all avenues to escape the death sentence imposed on them for their role in the attempt by nine Australians – the Bali Nine – to smuggle 8.3 kilograms of heroin out of Bali.

Over the past decade, Chan and Sukumaran have been tried in the Denpasar District Court, appealed to the Denpasar High Court, and brought two appeals before the Supreme Court (a “cassation” and a PK “reconsideration”). They have not won once, and their attempt to bring another PK was rejected last week on procedural grounds, without consideration of its merits.

Along the way, the lawyers for the Bali Nine have argued before Indonesia’s Constitutional Court that the death penalty breaches the “right to life” in Indonesia’s constitution. They failed as well.

Chan and Sukumaran also made clemency applications to the President, asking for jail instead of death. Joko “Jokowi” Widodo refused their requests, reportedly without even reading them. Their rehabilitation and reform in prison counted for nothing, despite the Constitutional Court having previously said it should be grounds for clemency.

Their lawyers have said Sukumaran and Chan now plan to appeal to the Administrative Court, but an earlier challenge to presidential clemency powers was rejected by that court. It is a bitter irony that it did so in relation to the five-year sentence cut former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono granted another Australian drugs offender, Schapelle Corby.

Time is now running out for the only two members of the Bali Nine still facing death. Indonesia’s Attorney-General, Muhammad Prasetyo, who organises and oversees executions and other criminal punishments, seems to have made up his mind to move fast. The Australian embassy in Jakarta has now been notified that Chan and Sukumaran will be executed within the month.

It will mark a significant shift in Indonesia’s approach to the death penalty, reversing a slow, decades-old trend that many observers had hoped might eventually lead to abolition. From 1989 to 2013, an average of only two prisoners were executed each year, and from 2008 to 2013 Yudhoyono imposed an informal moratorium on executions.

Since Jokowi became president, however, six have already been executed. The Attorney-General’s office has notified several embassies of its intent to execute more foreign nationals soon – maybe as many as eight, on some reports. There are even rumours circulating that up to 60 offenders might be put to death by year’s end.

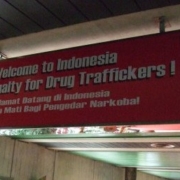

While there are 17 offences on the books in Indonesia for which death can be imposed, it is usually only given for terrorism, serious premeditated murders and drugs offences. The new administration’s enthusiasm for executions appears to be mainly directed at drugs offenders.

In Indonesia, opinion about the death penalty remains split. On the one hand, some Indonesian officials and media outlets have come out against it, condemning it as barbaric and a breach of fundamental human rights. Even Jimly Asshiddiqie, the former chief justice of the Constitutional Court who presided when the death penalty was upheld, says it might now be time to abolish it. This abolitionist group points out the apparent hypocrisy of Indonesia actively seeking clemency for its own citizens on death row in other countries, but still executing in Indonesia.

On the other hand, many – perhaps most – Indonesians appear to support the death penalty or at least do not object to it, particularly for drug crimes. They distinguish between abused domestic workers facing death in Saudi Arabia or Malaysia for killing their employers and drug traffickers, who they see, rightly or wrongly, as mass murderers.

There are also strong political reasons for the new push to execute drug offenders, including foreigners. It fits with public perceptions in Indonesia of a rising tide of illegal drug use and may well reflect Jokowi’s own personal views – Indonesian observers say he is morally and socially conservative.

He is also, however, proving to be a weak and politically vulnerable leader. Jokowi was inaugurated last year amid a wave of reformist euphoria. A hundred days later, the deals he has cut with his political opponents (and even his own political party) to get his stalled agenda through has left him with a reputation for compromise and indecisiveness that is eroding his popularity. His deadly political enemy, Prabowo Subianto, revels in a hard-man nationalist image and is watching his every move. Giving way to pressure from Australia to spare Sukumaran and Chan would play straight into his enemies’ hands. Now that Jokowi has committed to these executions, he probably cannot afford to back down, even if he wanted to.

Like Chan and Sukumaran’s lawyers, the Australian government has, in fact, done a great deal – both publicly and behind the scenes – to save them. However, its considerable efforts have come to nought. Although the government of Australia must continue agitating for the lives of its citizens the reality is that there is very little we can do to shift Indonesia, which sees itself as a rising regional power.

The government is right to have resisted calls to withdraw our diplomatic representation. That would cut off access and our ability to exert what influence we do have. When Brazil and Holland called their ambassadors home after their nationals were executed in January, Jakarta hardly blinked.

It would be equally pointless to terminate our aid program, which is well regarded in Indonesia and provides real benefits to many poor people, especially in eastern Indonesia. They would be the main ones to suffer. In any case, history shows that Indonesian governments usually respond to foreign ultimatums by hardening their position. Our capacity to support Australians in trouble in Indonesia in the future would be severely compromised.

Perhaps the only thing that might shift Jokowi now is a wave of domestic protest in Indonesia, and there is no sign of this happening. Sadly, that means there is very little hope left for Sukumaran and Chan and very little Australia can do about it.

It also reflects a grim truth about the administration of the death penalty: politics turns it into a game of chance, which is one reason so many countries have abolished it.

This article was originally published in The Age on 11 February.