“Istirahatlah Kata-Kata” is a quiet and moving portrayal of a poet’s life in exile.

The Indonesian title of the film “Solo, Solitude”, released in January in selected Indonesian cinemas, is instead “Istirahatlah Kata-Kata”, which can be roughly translated as “Rest Now, Words”. Throughout this sparse and quietly composed film, this evocative sense of a poet’s weariness pervades. The viewer, too, longs for the poet’s rest.

The film begins with veiled hostility, as we watch four figures fill the screen. A young girl remains silent, her mother’s hand resting on her shoulder. One policeman questions her while another rifles through shelves in the background.

“Istirahatlah Kata-Kata” describes several months of the fugitive life of poet and activist Widji Thukul, which began in 1996 as then President Soeharto’s New Order cracked down on growing resistance to the authoritarian regime. Widji, a member of the People’s Democratic Party (PRD), was among many who fled when they were marked for arrest and the uncertain, often fatally violent, fate that followed detention. The film depicts Widji’s journey and friendships within the network of activists, intellectuals and unionists that protected and concealed dissidents. Yet this political context is only vaguely – and very empirically – outlined at the beginning of the film, a strategic creative decision that has challenged some viewers, especially those who understand little of this part of recent Indonesian history.

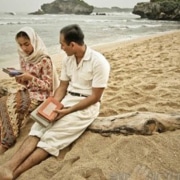

Instead, director Yosep Anggi Noen has built a universe of lush soundscapes and deep colour to frame the quotidian quiet of Widji’s exile in Kalimantan, and the loneliness of his wife Siti Dyah Sujirah, or Sipon, in their home town of Solo. There is little drama in the film until its final scenes: Widji’s poetry narrates the protagonist’s psychological state as he travels through the landscape, his verses of resistance hinting at the political context that the film only sparingly explores. Meanwhile a shrill whistled tune links scenes of home and flight. We watch in the dark as Widji fails to fall asleep, to write, or to think. When eventually we witness Widji’s poetry return to him, he rests at last and the mood of the film lifts.

The film’s English title suggests a solitude that is not a marked feature of the narrative. Widji is protected and rarely alone. Sipon and their children continue their lives under the close surveillance of gossiping neighbours and police. But the film certainly evokes the accumulating tiredness of a family living without certainty of a future together, and the brief joy and ongoing pain that reunion brings.

Even as the film rises to its conclusion, the pictures Anggi paints for the viewer remain restrained, long shots undisturbed by excessive dialogue or multiple viewpoints. The sometimes gentle, sometimes startling sounds – of plates scraping, engines rattling and bodily movements – set the mood for scenes that roll between fearful encounters with would-be and genuine soldiers and congenial meetings with like-minded friends.

The film has been immensely popular, especially among young Indonesians, many of whom were barely school-age during the period the film depicts. Initially showing on only 19 screens, it quickly expanded to 32 screens, and by early February, had been viewed by more than 50,000 Indonesians.

When I arrived to see “Istirahatlah Kata-Kata” at the cinema at Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM), a cultural centre in Jakarta that has dominated Indonesian artistic output in many fields since its inauguration in 1968, I was surprised to see hundreds of people milling in and around the lobby. Large groups of young people, clearly attending as part of study courses or social clubs, filled the cinema – perhaps surprising given there has been little recognition of Widji Thukul’s poetry or activism outside of human rights and arts circles. The line from his poem “Peringatan” (“Warning”), which insists “thus there is only one word: fight!”, has become a common catchcry of resistance among young Indonesians, but as one academic observed at a poetry reading also held at TIM, few know where the words come from. The film’s popular appeal is also its strength. While the TIM audience, perhaps more familiar with the film’s background story, remained serious throughout, a screening I attended at Jakarta’s Blok M mall coaxed many laughs from a less solemn audience.

It’s unlikely that those who know little of Widji Thukul, or the work of activist movements and their supporters leading up to the ousting of President Soeharto in 1998, will learn much more from this film. But in a socio-cultural and political environment that remains repressive of leftist ideologies and has failed to reverse the impunity enjoyed by perpetrators of human rights abuses, the popularity of “Istirahatlah Kata-Kata” speaks volumes for the craft of film and its potential to utter the unutterable. And the film’s success at international film festivals points to its broader appeal as an exploration of poetry and exile that has captivated audiences around the world.