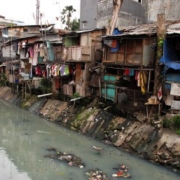

On 9 May, the North Jakarta District Court found that Basuki ‘Ahok’ Tjahaja Purnama had violated Article 156a of the Criminal Code (KUHP) and sentenced him to two years in prison. Photo by Dharma Wijayanto.

Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama has had a rough few months. Until recently, the Christian and ethnic Chinese Ahok was the governor of Jakarta – and one of the most committed reformers and effective administrators to ever lead the capital. In April, he lost a run-off election for governor, for a second term that would have begun in October. Then, on 9 May, he was convicted for blasphemy, in what was the most significant use of Indonesia’s blasphemy laws for political ends in the country’s history. The election loss and his trial were undeniably linked.

The blasphemy charges were clearly brought against him to undermine his chances of election. Worse, they related to his alleged misuse of a Qur’anic verse that the Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI) and Islamist groups say prohibits Muslims from electing a non-Muslim as a leader. So every mention of his blasphemy case reinforced the message of his unelectability.

Many commentators have looked at the broader implications of Ahok’s loss and his conviction for blasphemy. In this article, I instead offer a legal analysis of the decision itself. What arguments did the court hear and what did it accept?

Before looking at the decision it is important to briefly review key aspects of the case against the former governor. Ahok was found guilty of violating Article 156a of the Criminal Code (KUHP) for publicly expressing feelings insulting or defaming a religion practiced in Indonesia, and was sentenced to two years in prison. As an alternative, prosecutors had initially indicted him for violating Article 156, which prohibits expression of hatred or contempt for a particular group in society. Some thought that the sentence that Ahok received was surprising given that, in the end, prosecutors had pursed the lesser charge and did not ask for a custodial sentence.

In any case, the charges related to statements Ahok made on 27 September during an official visit to the Thousand Islands, off the coast of Jakarta. There, he gave a speech to about 100 people – primarily fishermen, the general public and government officials. He claims that some members of the audience were not really listening to him and, to get their attention, he said something along these lines: “You don’t have to vote for me and you probably won’t, if you’ve been misled by those using Surat Al Maidah 51″ (Verse 51) of the Qur’an in a misleading way.”

Verse 51 warns against Muslims having Jews and Christians as their auliya. There is much debate about what auliya means – “allies”, “friends” and/or “leaders”. Some high profile Islamic figures took what Ahok said as either an affront to those doing the misleading (that is, the ulama), or the Qur’an itself. His statement was recorded and then uploaded to YouTube, though it seems the video was edited before upload to make it more incriminating.

MUI issued a written warning on 9 October 2016, telling Ahok to focus on his job, and not to make insulting and provocative statements. Two days later, it issued a “religious opinion and stance” (Decision No. 981-a/MUI/X/2016). While not strictly a fatwa, this is how it became known. The decision said:

- Verse 51 contains an explicit prohibition on having Christians and Jews as leaders

- Ulama must therefore convey to Muslims that the verse means that voting for a Muslim leader is obligatory

- Saying that the verse is a lie is haram, and is defamation of the Qur’an

- Saying that ulama were being deceitful by conveying the argument that the verse contains a prohibition on non-Muslims becoming leaders is an insult to the ulama and the Islamic community

- Law enforcers must act firmly against every person who offends the Qur’an and Islamic teachings, using existing laws

Within a few weeks, the National Movement to Defend the MUI Fatwa (GNPF-MUI) had organised mass protests demanding Ahok’s imprisonment, attracting an estimated 150,000 people in November and 700,000 in December. Ahok was named a suspect in late November, and sentenced six months later.

The decision is long, more than 600 pages. Most of the transcript is taken up with summaries of what was said during the trial by witnesses, of which there were several dozen, most of whom were called by the prosecution. Like many other decisions of Indonesian courts, the decision contains lots of unnecessary repetition and did not have any headings, which made it hard to read. But surprisingly, it was otherwise methodical and written relatively clearly.

There are four aspects of the decision that are important to consider. How did the court interpret the meaning of auliya? How did it treat the video evidence? Why was Ahok’s statement considered blasphemous? And why did the court ignore the prosecution’s demand?

What does auliya mean?

Many witnesses called by the prosecution and defence emphasised that the precise meaning of auliya was unclear, noting that its meanings included “leader”, “close friend”, “defender” and “ally”. The court accepted this, saying:

“Differences of opinions such as these are common in the Islamic community, but in the Islamic community itself, it is not permitted to put blame on one or other the other, it is not permitted to declare one opinion correct and another one wrong, moreover to say that another opinion is a falsehood. Rather, there must be mutual respect for different opinions – the difference is in fact a blessing from god.” (page 604)

In short, then, the court did not conclude that auliya meant leader and, hence, did not find that Verse 51 prohibited Muslims from choosing Christians and Jews as their leaders. This goes against what MUI said in its opinion and what its experts had said in court.

The video evidence

There was some controversy about the video, with some claiming it had been doctored. The uploader, Buni Yani, was named a suspect for inciting religious or ethnic hatred, under Article 28(2) of the Electronic Information and Transactions Law. When he uploaded the video, he reportedly included a transcript but removed the word “pakai” from Ahok’s statement. This was important because it changed the meaning of what Ahok said from “Verse 51 was used by people to mislead” to “Verse 51 itself was misleading”. In short, with the word pakai, the criticism of misuse was directed toward the ulama; without it, the criticism was directed at the Qur’an itself.

The court almost completely ignored the claim that the video was doctored. It simply accepted that the police forensics laboratory had found no evidence that the video had been tampered with.

Also important was that the court did not discuss the validity of video evidence, even though the admissibility of video evidence has long been a matter of legal debate in Indonesia. For many years, courts have been inconsistent when deciding whether videos can be used in court to prove guilt. In some cases, video evidence has been allowed to be used but in many others it has not. Importantly, in many of these cases, the courts appear to have considered admissibility purely based on form (that is, a video), rather than checking the providence and reliability of each video. In this case there were quite sustained allegations that the video was doctored, but the court did not even consider the admissibility of the evidence, even if only to conclude that it was admissible.

Strangely, the defence did not seek to contest the admissibility of the video. Without it, the prosecution had very little evidence against Ahok. Most, if not all, of the witnesses who attended Ahok’s speech at the Thousand Islands testified that they had not paid much attention to what Ahok said. They didn’t pick up any blasphemy on the day. The fishermen said they were only interested in his programs, and the cameraman was concerned only with the quality of the footage. Only after they had heard about the alleged blasphemy did they go to YouTube to see what Ahok had said.

So the prosecution really only used these witnesses to establish that Ahok did in fact give a speech at the time and place alleged. Most of those who reported Ahok to the police had only seen his speech on YouTube. Instead of focusing on admissibility, the defence argued that because the witnesses did not experience the blasphemy first hand, the evidence was hearsay. This got the defence nowhere. The court rejected its hearsay claim because the witnesses later saw the video on YouTube.

What made Ahok’s statement blasphemous?

The court blurred the distinction between concepts of Verse 51 being “used to mislead”, rather than “being misleading of itself”. For the court, it was sufficient that Ahok had used the verse in connection with the concept of deception, which had a negative connotation.

Whether Verse 51 was used as a tool to deceive the community, or whether Verse 51 was a source of the deception itself, Ahok had belittled, degraded and insulted Verse 51 itself (page 604). And, because Verse 51 is part of the Qur’an, the court found that he had offended the Qur’an itself. Blasphemy had, therefore, occurred.

In reaching this conclusion, the court largely adopted conclusions drawn by the MUI opinion and the prosecution witnesses, many of whom were associated with MUI or conservative Islamic organisations. Ahok’s lawyers objected to the court’s almost wholesale adoption of the prosecution’s witnesses, claiming that testimony of those witnesses associated with the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) or MUI was not objective and should be ignored. But the court dismissed this, responding by saying “the main problem in this case is not a problem between the defendant and MUI or FPI” (page 614).

Similarly, the court rejected defence arguments that this case was all about politics and elections, rather than about blasphemy. In the eyes of the court, this was criminal blasphemy, pure and simple. Just because the case was heard in the leadup to the election did not mean it was related to the election, the court said. And, according to the court, most of the witnesses had no interest in the governor’s election. They were not politicians or associated with political parties; but rather were religious figures. Some even lived outside of Jakarta.

In fact, according to the court, the defendant had brought this all on himself because of his comments.

“The defendant, as governor and the servant of the community, must be statesperson-like – in addition to being clean, firm and honest, he or she must also be polite, and a model for the community he or she leads.” (page 614)

Why did the court ignore the prosecutors’ demands?

In the end, the court found that Ahok had violated Article 156a of the KUHP and sentenced him to two years in prison. This was despite the prosecution deciding, in its final submissions on guilt and sentence, to pursue charges only under the lesser Article 156 offence of hate speech, and to seek only a two-year suspended sentence. They said they changed their demand because only the Article 156 charges had been proved at trial.

The court justified ignoring the prosecution’s demand by pointing out that the prosecution’s indictment included both Article 156 and Article 156a as alternative charges. This meant that the court could simply choose the first alternative charge, given that, in its view, the elements of the offence had been established at trial, regardless of what prosecutors asked for.

The court has been widely criticised for doing this, although Indonesian courts are able to award a penalty larger than that put forward by prosecutors. This is true, but I think it might miss the real unfairness that occurred here.

The closing statements of the prosecution and the defence were not included in the case file, so the following point is speculative. But presumably, given that prosecutors sought conviction only under Article 156, their closing statements related to that provision only. Presumably, too, when it made its closing statement after the prosecution, the defence only felt the need to respond to the Article 156 case that prosecutors had argued.

It is highly likely that the defence did not anticipate that the court itself would turn to Article 156a, and so probably did not put forward any arguments against conviction under Article 156a. Ahok was thus a “sitting duck” for the Article 156a alternative, because, in the end, his defence team probably did not defend him against it.

The court also did not justify why it chose a two-year sentence, as opposed to a lesser or greater one, when a sentence of up to five years was possible.

Why did Ahok withdraw his appeal?

Despite the errors made by the court in this case, Ahok has decided to withdraw his appeal, and this was an understandable and pragmatic choice. First, with time served, concessions and probation, he will probably be free by mid-2018. If he appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, he might end up in prison for much longer. Appeal would involve rehashing the whole saga (and potential unrest) and could lead to a higher sentence.

It is also important to note that three out of the five judges who heard Ahok’s case were promoted just one day after they delivered their verdict against the former governor. The Supreme Court says the promotions had nothing to do with Ahok case, and had been in process for months. This may be true, but it could also be an indicator of the futility of an appeal.

Although Ahok has withdrawn his appeal, prosecutors have said they will go ahead. This may be the first time in Indonesian legal history that prosecutors have appealed to seek a lighter sentence. It would be ironic, perhaps, if prosecutors’ efforts to win Ahok a lighter sentence resulted in the opposite outcome, but that remains a real possibility.