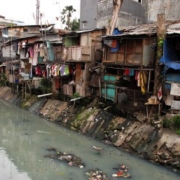

According to the Jakarta Legal Aid Foundation (LBH Jakarta), more than 8,145 families were displaced in 2015, in 113 separate evictions. Photo by Ian Wilson.

Sri rummaged through shopping bags stuffed with kitchen utensils. “Where’s that clothes line?” she sighed. The sky was overcast and beginning to darken. It would rain soon, and heavily. It was the peak of the wet season. Sri and several hundred others had just lost their homes in a forced eviction in the south of Jakarta, and they needed cover. With the help of a neighbour, Sri strung up a tarpaulin donated by a political party, using the clothes line to secure it to the perimeter fence of an adjacent apartment block. From their balconies above, apartment residents filmed the drama below.

Earlier that morning, a combined force of 600 public order officials (Satpol PP), police and military officers had converged on the site. A final eviction notice had been served the previous day. With hundreds of residents refusing to leave, public order officers in riot gear pushed their way through a rudimentary barricade blocking the street. Men, women and children were dragged screaming and crying from their homes, after which the bulldozers moved in. Within an hour, the neighbourhood was no more.

Huddling under the tarpaulin as the first heavy drops of rain began to fall, I asked Sri what she’d do next. She shrugged. “I don’t know. My family and I have lived here for 15 years. We’ll hang in here for now. Hope for compensation. The government offered us rusunawa (low-cost rental apartments) but they’re more than 30km from here. What about my kids’ schooling and my food stall, how will I afford the cost of travel and the rent, how will…” Her voice trailed off as she contemplated the uncertainties.

Sri’s home had been declared illegal by the Jakarta administration, which claimed that it was built on an allocated green zone, areas ostensibly earmarked for public parkland in a city where such spaces are rare. Yet, as with dozens of other neighbourhoods evicted on similar grounds, the land had been occupied for decades, incorporated within the city’s administrative structure, and connected to state services such as electricity and water – for all intents and purposes, legal.

The perception of an uncompromising enforcement of the rule of law has been pivotal to support for Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaha Purnama, or Ahok, particularly among the middle class. According to the Jakarta Legal Aid Foundation (LBH Jakarta), more than 8,145 families were displaced in 2015, in 113 separate evictions. A further 325 locations have been slated for eviction by the end of 2016, with many suspecting an upsurge in the months prior to the governor’s elections, scheduled for February 2017.

In a city like Jakarta, the “rule of law” is, in practice, more often than not a euphemism for rule by political expediency and the interests of the powerful. The governor’s unflinching stance has been popular with his middle-class constituents, as well as property and developer moguls and important political and financial backers, largely because they have been entirely exempted from it. Recent floods in the upmarket Kemang district for example, the outcome of layers of unregulated development, have not resulted in significant sanctions. Meanwhile, the poor neighbourhood of Bukit Duri in Tebet, South Jakarta, was recently evicted despite an ongoing class action suit challenging the city administration’s legal right to do so.

The north of Jakarta, in particular, has emerged as a battle ground. Developers and clients hungry for coastal property, facilitated by public–private partnerships under the mantle of developmentalism, have targeted some of the city’s oldest neighbourhoods and the diverse ways of life of those who live there.

Evictions and displacement are not new – they have long been part of what it means to be poor in Jakarta. The unprecedented scale of dislocations under Ahok, however, has become a catalyst for increasing mobilisation, action and networking by urban poor groups, residents and their allies.

Unlike social-media savvy middle-class supporter movements like Teman Ahok, poor people’s politics are diverse, fragmented and often appear unstructured and leaderless. As the product of necessity, they are overwhelmingly instrumental, opportunistic, and pragmatic: often the only effective strategies given the structural disadvantage of the poor.

Poor people already operate politically in everyday life, which requires the managing of complex and multiple relationships, including with the powerful, in order to hedge risk and keep options open.

A neighbourhood under threat of eviction may engage with a seemingly contradictory array of outside groups and interests ranging from human rights organisations, public intellectuals and trade unions to ethno-nationalist militias, Islamic mass organisations, a variety of aspiring electoral candidates and political parties. Each may offer possibilities for amelioration or assistance, some immediate, some long term.

Major political parties, for example, have generally shown little interest in, or sympathy with, the plight of Jakarta’s poor and displaced. A recent exception is the Greater Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra), the former party of the governor, from which he acrimoniously split in 2012. Party flags and functionaries are now prominent at evictions, and party-affiliated groups regularly provide temporary shelter to the displaced.

That Gerindra is using the plight of the poor, and the race card, as a political wedge in its bitter pursuit of its former poster boy is not lost on many residents. But as one explained, “It doesn’t matter. If it gets our rights on the agenda, then so be it. Who else is going to do it?”

As urban village, or kampung, residents know all too well, politicians will shift positions and priorities when it suits. Opportunities need to be seized.

Resistance is also driven locally by resident’s forums, community leaders and urban poor advocacy, as well as support networks such as the Jakarta Urban Poor Network (JRMK) and Ciliwung Merdeka. Strategic actions have included class suits, street protests and vigils, and physical resistance to removal and neighbourhood beautification campaigns that challenge the characterisation of communities as slums. It is now common for evicted residents from one part of the city to be present at other evictions, reflecting a growing sense of inter-kampung solidarity.

Beyond the disconnected mobilisations and shaky alliances there are two main positions on which there is consensus. One is that Ahok must go, an attitude often referred to by the acronym ABA (Asal Bukan Ahok) or “As long as it’s not Ahok”. Initially embraced by many as a reformer, experience has shown that his vision for Jakarta is irredeemably “anti-kampung” and hostile to the poor, and that he’s a willing hostage to the interests of developer giants such as Agung Podomoro.

The aggressive, and at times spiteful, manner in which he has pursued his evictions regime has extinguished any remaining goodwill. As one elderly resident said: “People say he’s a tough guy, but only towards the weak. He has no heart.”

The second is that the promises made by President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo during his 2012 campaign for governor, formalised into a political contract, should be fulfilled. Key to these was a commitment to end evictions, revitalise, rather than demolish, kampung and provide tenure security to neighbourhoods in existence for 20 years or more. Brokered by a number of urban poor groups, this political contract was central to the large mobilisation of the poor in support of Jokowi and his then deputy Ahok.

That many of these neighbourhoods, such as Sri’s, have since been subject to forced eviction has further compounded their sense of betrayal, abandonment and anger.