The new criminal code is riddled with contradictions and conflates sexual orientation with sexual practice. Photo by Flickr user Johanes Randy Prakoso.

Late last month, authorities in Aceh announced they would begin enforcing the province’s Shari’a Criminal Code, known as the Qanun Jinayat, which extends Islamic law to non-Muslims. The code explicitly outlaws (forms of) homosexual and lesbian sex, prompting some activists to encourage gay and lesbian Acehnese to escape from the province. A closer examination of the code, however, reveals that it is riddled with contradictions, and the legal basis for criminalising sexuality is weak.

The implementation of the code was made possible by the special autonomy laws offered to Aceh from 1999 in an attempt to keep secessionist demands in the resource-rich province in check. Islam has long played a central role in Acehnese identity and culture but Aceh’s grievances with the Indonesian state did not actually coalesce around establishing an Islamic state. Rather, the main objection of the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) – and, indeed, the Acehnese people – was with Jakarta’s exploitation of the province’s natural resources and the oppressive actions of the security forces. The central government and the military saw shari’a law as a political solution to the conflict in the province, and so it was a key part of the peace exchange that ended the conflict in 2005.

The Qanun Jinayat has been roundly criticised – both in Indonesia and abroad – because it clearly violates human rights, notably through its use of corporal punishment, restrictions on freedom of expression, and control of women’s dress and freedom of movement. But the code has attracted the most attention for its preoccupation with issues of sex. The definition of sexual misconduct in the code is confusing, and it conflates sexual practices with sexual orientation.

The law criminalises liwath, which is defined as anal penetration between men, and carries a punishment of 100 lashes, a fine of 1,000 grams of gold or 100 months in prison. It is unclear whether criminalising liwath is intended to criminalise gay sexual orientation. There is an obvious difference between sexual practice and sexual orientation: not all gay men practice anal sex, for example, while some heterosexual couples do.

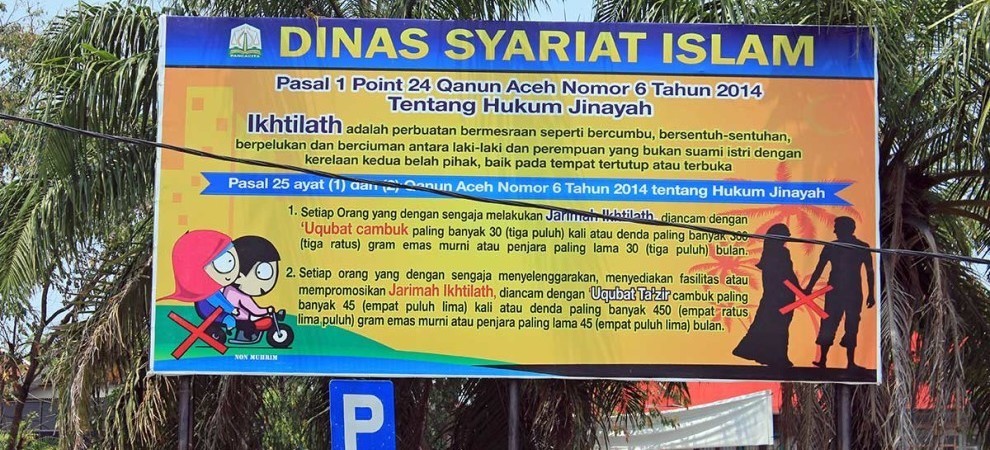

The confusion does not stop there. Ikhtilath between heterosexual couples is also criminalized. Ikhtilath refers to an act of intimacy in the form of flirting (bercumbu), kissing, touching, hugging between unmarried men and women, and carries a punishment of 30 lashes, a fine of 30 grams of gold or 30 months in prison. Further, a man and woman who are not legally married and are in close proximity (for example, secluded in a room) are seen as committing khalwat, and can also be charged with adultery.

These differences between ikhilath, khalwat, and liwath suggest that gay sexuality, as long as it does not involve anal sex, is not considered an offence under the law. Ikhilath and khalwat offenses only apply to heterosexual couples. Homosexual couples engaging in intimacy are, in theory, not committing an offence. What makes the law more look more like a joke (albeit a scary one) is the absence of a provision making oral sex a crime.

The definition of musahaqah, which is intended to criminalize lesbian sex, is also highly confusing. Musahaqah is defined as the act between two or more women of rubbing (menggosok-gosokkan) their body parts or vagina (faraj) for sexual pleasure. But lesbian couples do not only derive pleasure by “rubbing”. As with gay couples, they can also derive pleasure from various forms of sexual practice, for example, oral sex. Sex does not necessarily involve anal sex, penetration, or rubbing body parts.

This definition does not, however, appear to have affected how officials have implemented the law in practice. In October, two young women were arrested by shari’a police on suspicion of being lesbians. Their only crime was, apparently, hugging in public.

The most concerning part of the Qanun Jinayat is its potential to exacerbate sexual violence. Articles 48 to 56 are concerned with rape. Under the law, in the absence of sufficient evidence, a rapist can recite an oath five times: four times declaring that he is not guilty and the fifth time taking an Islamic oath, stating that he will receive laknat Allah (God’s wrath) if he is lying. The law suggests the rape victim do the same. If both the suspect and victim take these oaths, they will be free from uqubat (punishment). Rapists may well walk free, while rape victims lose their dignity and access to justice.

The Qanun Jinayat also allows suspects to choose between corporal punishment, imprisonment, or a fine in gold. These three options show the clear class bias of this law. Those who can afford to pay the fine will be freed from whipping but what happens to poor offenders?

Given these concerns and contradictions, how can we believe that the Qanun Jinayat upholds the principles of justice and equality (keadilan dan keseimbangan) and protection of human rights (perlindungan hak asasi manusia) as it claims in article 2?

Despite media reporting to the contrary, one thing that LGBT Acehnese have on their side is that there is nothing in the Qanun Jinayat that criminalises their sexual orientation. As a close reading of the law shows, only specific sexual acts are criminalised. The clumsy way the law is administered, however, means that this may be cold comfort at best.

The question is why lawmakers feel the need to regulate sex in the crude and oppressive way they have in the Qanun Jinayat. The fact that they have chosen to define gay sex simply as penetration signals their lack of imagination, as well, of course, as their hostility to sexual difference. Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s Little Prince might have said that grownups are odd because they lack imagination, but these lawmakers are even worse. Not only are they odd, they are sadists too.