The One Map policy aims to harmonise different land use maps to reduce competing claims to land. Photo by Rainforest Action Network on Flickr.

Land and agrarian conflict is one of the biggest national development challenges facing Indonesia. Government agencies have traditionally had the authority to make their own sectoral maps, but no one standardised map existed, resulting in overlapping and conflicting claims to land.

The government has embarked on a project to develop a single reference map, which will harmonise all maps from different state agencies to a scale of 1:50,000 to prevent overlapping land use claims. For the first time, ministries and state agencies are being pushed to work together to create a common map.

In February, President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) signed a Presidential Regulation (perpres) on the acceleration of the One Map policy, part of his eighth economic stimulus package. The perpres aims to speed up the process of synchronising all official maps to support land acquisition for infrastructure development and provide a better business environment. But the One Map policy is not merely a technical process. It is highly political, involving contestation both among government agencies and between the government and communities.

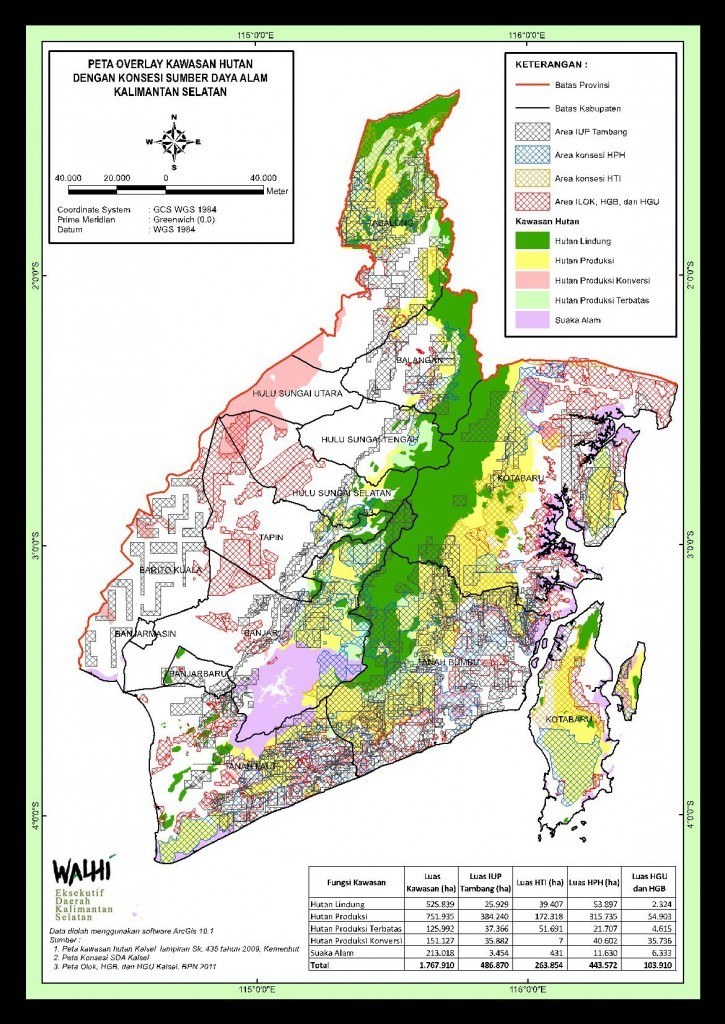

Researchers and civil society organisations have documented many examples of conflicting land zoning and permits. This map demonstrates the chaotic overlap of mining, logging, and industrial plantation forest concessions in South Kalimantan. Image by Walhi South Kalimantan.

Creating one map

The One Map policy was first discussed in a cabinet meeting in 2010, when the Presidential Working Unit for the Supervision and Management of Development (UKP4) showed President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono two forestry maps produced by the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Forestry. On seeing the vast differences between the two maps, Yudhoyono instructed UKP4 and related ministries to develop one authoritative map that could be used as a national reference.

Yudhoyono hoped to use the map to serve the needs of the US$1 billion agreement between Norway and Indonesia aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation. This deal included a moratorium on the release of new forest and peatland concessions, beginning in 2011. The first moratorium lasted two years, and in July last year President Joko Widodo extended it for a second time, to 2017. Moratorium maps – which have been updated by the government every six months – have been used to formulate the single uniform map. About 65 million hectares of land are now covered by the moratorium.

The Jokowi administration intends not only to accelerate the One Map policy for reducing deforestation, but also expand its use into other areas. Not only will it clarify administrative boundaries, help to resolve land use conflicts, and improve conservation and disaster management, but it will also help the government to create better spatial planning for economic development.

A team for the acceleration of the One Map policy is led by the Coordinating Minister for the Economy Darmin Nasution and includes the minister of home affairs, the minister of national development planning, the minister of finance, the minister of agrarian and spatial planning, the minister of environment and forestry and the cabinet secretary. An executive team under the Geospatial Information Agency (BIG) is being tasked with covering technical issues related to mapping, monitoring and evaluation, and data exchange. Some 19 ministries and governmental institutions are involved in preparing the map.

In December 2014, BIG launched a basic geospatial map, along with several thematic maps, such as a national mangrove map, a national maritime characteristics map, and a national seagrass map. Through the perpres, the government aims to finish all thematic maps in June 2019.

Political challenges

Technically, synchronising thematic maps from the various governmental agencies is possible. But one of the main obstacles to developing a single map is the reluctance of government agencies to collaborate, particularly those that have the authority to issue permits. With the One Map policy, these agencies still have authority to issue permits, but their opportunities for gaining illicit economic benefits will be greatly reduced.

For years, actors in governmental agencies in production-oriented sectors, such as mining, plantations and logging, have benefited from unclear, contradictory and inconsistent regulations. District governments have reinterpreted these unclear regulations to issue licenses both to enhance local revenue and for rent seeking. The situation has been exacerbated by the lack of a common map and a general lack of transparency. The fact that different agencies use different maps with different, and sometimes outdated, data also complicates law enforcement.

Another vital issue is the incorporation of customary land into the One Map. Lack of recognition of customary rights to land has been one of the major causes of conflicting claims to land. Indigenous and forest-dependent groups, facilitated by civil society organisations, have actually used participatory mapping techniques to map indigenous land since the mid-1990s. Despite these efforts, the state has been reluctant to recognise customary lands.

In the past, the government relied on a definition in the 1999 Forestry Law, which described customary forest as state forest located in the areas of customary law communities. In 2013, however, the Constitutional Court ruled that this Article 1(6) and a number of other clauses in the 1999 Forestry Law were unconstitutional, effectively voiding state ownership of customary forest and providing indigenous communities with the opportunity to obtain their rights to manage their land.

In 2010, a group of civil society organisations, including the Network for Participatory Mapping (JKPP) and the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago (AMAN), established the Ancestral Domain Registration Agency (BRWA) to advance the participatory mapping process and record customary areas in Indonesia for integration into the One Map. The Constitutional Court’s landmark decision encouraged BRWA to accelerate the customary mapping processes. According to AMAN, indigenous lands cover about 40 million hectares of the country.

These efforts have faced significant resistance from the Geospatial Information Agency, which questions the standards of participatory mapping processes. Civil society activists have argued, meanwhile, that by conducting participatory mapping processes, they are, in effect, doing the government’s work. If the government believes the methods used by organisations like AMAN and JKPP do not meet its standards, they argue, then it should conduct participatory mapping of customary land itself.

Activists have recently become concerned that Jokowi is too focused on using the One Map to support land acquisition for infrastructure development and a better business environment. He previously promised to establish an indigenous peoples’ task force to identify indigenous land for integration into the map – but almost a year after it was delayed, the task force has yet to materialise.

Towards better land use planning

Of course, the One Map policy will not reduce land conflict overnight. It only provides the basis for improved decision making. But despite the many obstacles, the perpres is an encouraging sign that the government is serious about improving land use planning, in particular through the way that it pressures government agencies to work together. Through the perpres, the government has developed an action plan for 2016-2019, which includes a range of targets designed to accelerate the One Map policy. Ministries and state agencies are required to provide information and if there are problems in the synchronisation of data, an acceleration team can make recommendations to resolve the problem, including by increasing budget allocations. The president is keeping an eye on its implementation through his office, which is responsible for overseeing the One Map policy.

Leadership from President Jokowi is crucial to ensure improved coordination between ministries and agencies. He must also meet his commitment to establish the promised indigenous peoples’ task force and push forward on efforts to pass the long-delayed law on indigenous peoples’ rights. Wider public participation and control over the One Map policy is also needed, not only in compiling and synchronising data but also in determining how the map will be used. Strong leadership and popular control are the keys to making the One Map policy work.