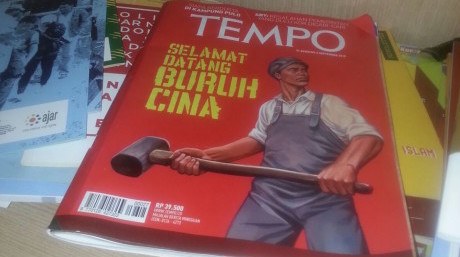

Although it found just one case of large-scale recruitment of Chinese blue-collar workers in Indonesia, Tempo’s cover story described a “flood” of workers from “the land of the Pandas”. Photo by Robertus Robet.

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and members of his government have not shied away from anti-foreign rhetoric in their first year in power. The tone was set during the divisive 2014 Presidential Election, when both camps claimed to be more Indonesian (or more Muslim) than the other. Perhaps seeking to prove their nationalist credentials, Jokowi and other officials have made various public statements describing foreign powers as attempting to meddle in Indonesian affairs.

Sometimes these statements are directed at a specific target, such as foreign journalists, westerners or China. Often they are directed at an abstract and ill-defined foreign bogeyman. Opening the Asia Africa Conference in April, for example, Jokowi told delegates: “We must push for reform of the global financial architecture, to eliminate the domination of one group of countries over others.” When briefing Indonesia’s ambassadors in January, he told the envoys that Indonesia must avoid a situation where it had many friends internationally but its interests were harmed.

In the face of strident international criticism of Indonesia’s execution of narcotics criminals, Jokowi and his officials painted foreign protests as attempts to interfere with the Indonesian legal process. Approaching the second round of executions, Jokowi said: “There cannot be intervention in the death penalty because the executions are a matter of Indonesian sovereignty.” He seemed to ignore the fact that Indonesia goes to great lengths to save its citizens on death row in other countries, including narcotics offenders.

The Army chief of staff, Gatot Nurmantyo, (since promoted to military commander) went even further, describing the rampant circulation of drugs among Indonesian youth as part of a proxy war in which foreign entities were attempting to weaken Indonesian young people. Such comments are not uncommon from the military, which is known for its almost paranoid obsession with foreigners attempting to break up the country.

Politicians outside the government have also invoked the spectre of a foreign threat. National Mandate Party (PAN) founder Amien Rais told journalists recently that “global devils” would try to bring about Indonesia’s disintegration by encouraging secessionism while Indonesia’s economy was weak. Meanwhile, Golkar Party lawmaker Mukhamad Misbakhun attributed the plummeting rupiah to foreigners exacting revenge for Indonesian policies disliked by the US. Misbakhun’s statement, devoid of detail of the foreign entities and how they drove depreciation of the rupiah, is notable in its resemblance to the conspiracy theory tropes popular among hard-line Islamic groups.

In making these statements, Jokowi and other officials tap a rich vein of public opinion in Indonesia, which has its roots in the struggle against colonialism. A 12-city survey timed to coincide with the 70th anniversary of Indonesian independence this year produced a striking result: 79.9 per cent of respondents answered that the country was not yet free of “foreign domination”.

Jokowi’s rhetoric and actions toward foreigners has, however, been remarkably inconsistent. When Home Affairs Minister Tjahjo Kumolo recently attempted to impose new permit requirements on all foreign journalists, Jokowi stepped in and quashed the plans. Likewise, a couple of days before decrying the global economic order at the Asia Africa Conference, Jokowi invited foreigners to “make incredible profits” in Indonesia, and stated that Indonesia needed foreign parties to develop its infrastructure. More recently, he ordered that new restrictions on foreign workers entering Indonesia be eased.

It remains to be seen whether these two opposed discourses on foreign parties can coexist, with foreigners cast as threatening and, at the same time, a welcome source of economic assistance.

The tension between the two positions has already come to a head in relation to Chinese involvement in the economy. Opponents have accused the government of being controlled by “foreigners and Chinese”, using a play on words between the Indonesian word for foreign (asing) and a derogatory word for Chinese (aseng). Such slogans conflate Chinese nationals with Chinese Indonesians.

Social media has also been abuzz with rumours of burgeoning numbers of workers from China entering Indonesia, and trade unions have protested against foreign workers at demonstrations in Jakarta and Surabaya.

The usually sensible Tempo magazine took up this issue last week, running a cover story on a “Flood of Workers from the Land of the Pandas,” depicting Jokowi on the cover as a Chinese labourer. Tempo’s description of a “flood” of workers was sensationalist, given that the report revealed just one case of large-scale recruitment of Chinese blue-collar workers for an electricity project in Bali. The manpower minister responded in the magazine by saying that foreign workers, in fact, made up less than 0.1 per cent of the labour force. Nevertheless, those holding anti-foreign views will likely present the article as factual evidence that foreigners, and the Chinese in particular, are recolonising Indonesia.

The conflation of Chinese nationals and Chinese Indonesians in the “asing aseng” phrase is not new. Throughout Indonesian history, the use of anti-foreign rhetoric has repeatedly culminated in attacks on the ethnic Chinese minority, who have presented the weakest and closest target.

Anti-Chinese riots in Bandung in 1963 started as a protest against then President Soekarno’s warm relations with China. The 1974 Malari riots started as a protest against Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka, but culminated in anti-Chinese rioting in Jakarta. Then, of course, there was the killing and rape of Chinese Indonesians in May 1998 during the turmoil surrounding the fall of Soeharto. Unable to directly attack the actual adversary (communist China, Japan, Soekarno or Soeharto), the masses compensated by attacking Chinese Indonesians instead.

Writing in 1947, Chinese Indonesian author Tjamboek Berdoeri (Kwee Thiam Tjing) anticipated this recurrent scapegoating of Chinese Indonesians as a side-effect of anti-foreign sentiment. “In an era when various gangs of Indonesians accused the Dutch of wanting to recolonise Indonesia,” he said, “it was not the Dutch who were sought out, but [instead] the Chinese were slaughtered.” Sadly, it appears he is still right. Use of anti-foreign rhetoric by Jokowi and other political leaders creates a risk that Chinese Indonesians will once again become targets of violence.