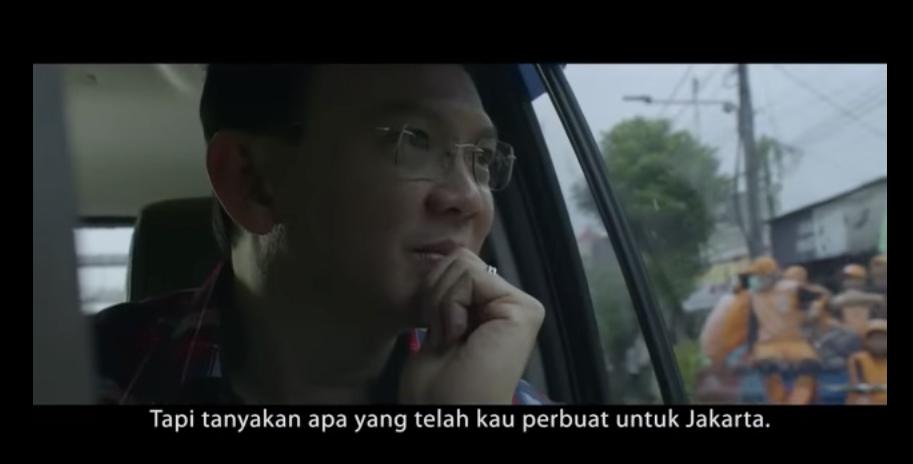

A still from the original campaign video, imploring viewers to ask what they have done for Jakarta.

With the election for Jakarta’s governor less than one week away, Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama and his running mate, Djarot Saiful Hidayat, have again sparked controversy, following the release of a campaign video that, like Ahok himself, has been accused of being “anti-Islam”. As Ahok awaits the verdict of his trial for blasphemy, everything he does in relation to Islam seems to be tainted.

The two-minute video, apparently made by a team of volunteers, was released by Ahok-Djarot on 9 April and promotes unity in diversity (the state motto) in a hard-hitting manner. The video is professionally produced and cinematically compelling. Its quality and style is more like an art house film than a campaign video. It draws on well-established cinematic traditions, which portray Indonesian nationalist themes.

Ahok’s video follows a number of characters through a loose narrative. These include rioters and their victims, ethnically Chinese badminton players, representations of the national symbol, the mythical garuda bird, school children, villagers and people representing different religions and ethnicities. The soundtrack includes part of Djarot’s speech from the “Konser Gue 2” campaign concert, on 4 February:

Brothers and sisters, all citizens of Jakarta, the time is drawing near. Become one of the historical actors and we can show that the Pancasila state has truly arrived in Jakarta.

The scenes begin with a terrified woman and her daughter in a car, surrounded by rioters, evoking the 1998 Jakarta riots, when the houses of ethnic Chinese were burned, ethnic Chinese women were raped and cars were burned. One of the rioters has a banner, “Ganyang Cina” (“Crush the Chinese”). A female bomb disposal official slowly walks down the road.

The scene changes first to a representation of Indonesian (ethnically Chinese) badminton players, walking up the steps, preparing to compete. This is followed by three figures representing ethnic diversity in Indonesia. A dancer with a garuda mask (but no wings) then arrives on the scene of the riot. There is a brief cut, in black and white, to a group of peasants marching through a forest, after which the garuda dances through the streets among the rioters.

We can also show that Unity in Diversity is, in fact, not just jargon but has already become embedded in Jakarta.

The camera focuses first on Javanese musicians, with player of the kenong (which usually marks the main notes at the end of musical segments), poised to play his instrument. Smoke from the riots is still billowing in the background. We then see Indonesian school children in their characteristic red and white uniforms, who are learning about the state motto from a teacher who is wearing a head scarf, and has written an explanation of the motto on the blackboard: “different but united”.

Next we are inside a house, where children are watching the riots on television. Their father sees the riots on the television and appears ready to leave the house. He stares at the camera and we see brief images in black and white of actors portraying a famous independence fighter, Sutomo (Bung Tomo), and then the first Indonesian president, Soekarno, reading the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, Vice President Hatta at his side.

Whoever you are, whatever your religion, whatever your ethnicity, wherever you come from, you, brothers and sisters, are all our brothers and sisters in one nationality and one nation and all have the same rights and responsibilities.

The video then returns to the riots where the woman and her daughter have left the car and someone with a baton is approaching. This turns out, luckily, to be a police officer – the woman and her daughter are safe.

The scene then moves to representatives of the six religions praying together in a pendopo (verandah-like structure, with a roof but no walls), followed by skateboarders and cyclists in a skate park (like the one installed by Ahok in Kalijodo). They are accompanied by ondel-ondel, large puppets, characteristic of Jakarta, used in ceremonies. These are said to represent the spirits of ancestors and were traditionally used to ward off calamities and wandering evil spirits. The scene then shifts to Javanese masked dancers followed by the three representatives of the many ethnicities in Indonesia and the peasants marching through the forest.

The segment culminates with the badminton players winning their match as the crowd roars with pleasure. This symbolises the victory of the badminton players, Kevin Sanjaya Sukamuljo and Markus Fernaldi Gideon, who won the All England competition in March. One of the players is then embraced by the mother from the riots and the father from the scene with the television. Both parents now have grey hair – 19 years have passed since the riots. The scene cuts to the people from the three different ethnicities, now happily together in a kampung.

Don’t ask, “Where do you come from?”; don’t ask, “What is your religion?” but ask, “What have you done for Jakarta?”

The different threads of the story are now brought together. The garuda dancer is in the skate park and removes his mask and the bomb disposal officer removes her helmet. Indonesian children (with an ethnic Chinese child in the foreground) are outside, saluting the flag. Then Ahok’s “orange troops” (who assist with waste management around the city) are cleaning a river. Order has been restored. Ahok pulls up in a car, with the orange troops in the background, and is greeted by a cheering crowd and his running mate, Djarot. The final image urges Jakartans to “vote for diversity, Basuki-Djarot”.

Ahok’s opponents, including high profile Muslim preacher, Abdullah Gymnastiar (AA Gym), have accused this video of being anti-Muslim. Their criticism has focused solely on the scene of the riot, where some of the men wear peci (caps worn predominantly by Muslims) and scarves. Using a hashtag #ahokjahat (Ahok is evil), they have accused Ahok of depicting the Muslim community in a bad light and making the Chinese (the badminton players) the heroes. There have been heated debates on television between the two opposing sides.

Ahok’s detractors are being very selective. They make no mention, for example, of the positive representations in the video of the Muslim teacher, the Muslim representatives of the multi-faith group in the pendopo or the two national heroes, Soekarno and Supomo, both Muslims, the latter of whom would recite, “Allahu Akbar! Merdeka!” (“God is Great! Freedom!”) at the end of his speeches on radio. Nor is there mention of the fact that the video is a narrative – from chaos at the end of the Soeharto era, to order now. Djarot, who was not involved in making the video, commented that the scene about the 1998 riots was inserted to remind people that such an event must never happen again.

Gerindra, a party backing Ahok’s rival, Anies Baswedan, reported the video to the police for being anti-Islamic. The video was taken down from Ahok’s social media accounts, apparently because it did not fit the General Election Commission’s specifications that campaign advertisements must not exceed 30 seconds.

Complaints about the length of the video have provided a suitable excuse for Ahok-Djarot’s team to remove controversial passages. Unfortunately, the 30 second version has been gutted and lacks the continuity and impact of the two minute video. The interesting question is will it also lead to Anies chopping his own 80 second campaign video on diversity to half a minute?