Scholars have said China had an “authoritarian advantage” in responding to SARS in 2002-2003. But in the case of Covid-19, there appears to be no such advantage. Photo by Antara.

Is Indonesia up to the task of responding to coronavirus disease (Covid-19)? Can its political institutions offer any hope that Indonesia will emerge from the pandemic intact?

The experience of other countries may be demonstrative. In the Journal of Chinese Political Science (19 July 2012), Jonathan Schwartz compared how authoritarian China and democratic Taiwan responded to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic of 2002-2003. Schwartz found that China had an “authoritarian advantage” over its neighbour Taiwan, and because of that, was able to respond to SARS more effectively.

He described three factors that led to China’s comparative success. First, the centralisation of power made coordination easier. Second, the relationships between these coordinated institutions were better. Third, there was strong public trust in the government, which encouraged widespread public participation in responding to the crisis.

Schwartz’s research revealed that there is a significant relationship between the type of regime and the response to a pandemic. But looking at how governments have responded to the coronavirus threat, it seems that his “authoritarian advantage” thesis does not apply.

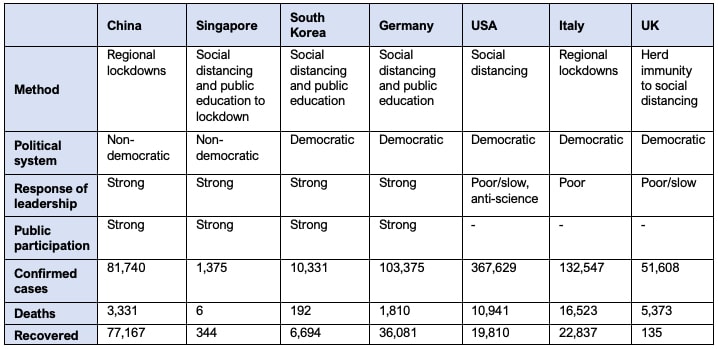

The success of countries like Taiwan, South Korea and Germany in limiting the spread of disease undercuts Schwartz’s argument. These countries prove that the principles and tools of democracy, such as transparency, participation and public awareness, have been able to prevent disastrous consequences from the virus. South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha even said outright that it was her country’s democratic principles that had helped it tackle Covid-19.

But on the other hand, non-democratic countries like China and Singapore have also had similar outcomes to democratic countries like Taiwan and South Korea. At the same time, non-democratic countries like Iran have responded poorly, as has the democratic United States of America.

Policies like partial or complete lockdowns of certain regions, as well broader implementation of social distancing are not sufficient to explain success either. Sweeping restrictions on movement appeared to work in China, but have not been successful in Italy, and have resulted in significant social tension in India. Meanwhile, democratic governments in Germany, South Korea and Taiwan were able to encourage social distancing while maintaining transparency and avoiding high fatalities.

Looking at the experiences of China, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea, it is clear that the type of political regime is not the sole determinant for preparedness or effectiveness in responding to a pandemic like Covid-19. So what factors do affect success? To answer this question, we can compare these countries to the experiences of the United States and the United Kingdom.

The USA and UK are two large democracies that let the pandemic get away from them. Many observers blame US President Donald Trump for the spread of the virus in the USA. Trump downplayed the seriousness of the threat and was slow to respond.

Trump’s poor leadership affected trust in medical authorities. Limited public faith in the US medical authorities meant that the public treated policies designed to control the pandemic with a degree of scepticism, and it was difficult to control the virus.

In the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson initially adopted the reckless policy of “herd immunity”, allowing the virus to spread through the community until enough people became immune that transmission was reduced. Johnson claimed that social distancing would only result in fatigue in the community. But the policy did not account for the fact that many young seemingly “healthy” people have also required hospitalisation and resulted in major costs for the country, with soaring rates of infection.

Trump and Johnson are alike in that they both rely on populist and anti-intellectual rhetoric to attract support. They are vastly different leaders to German Chancellor Angela Merkel. From the first signs of the virus, Merkel appeared to seriously prepare Germany for an outbreak there. Likewise, in South Korea, a week after the first case was identified, the government ordered 20 companies to begin producing rapid tests, and a mass testing campaign was implemented. In Singapore, on 3 February, the health minister was already speaking to parliament about how the country should respond to a potential pandemic.

In the table above, it is clear that the success or failure of a country in responding to the pandemic does not depend on the type of regime (democratic or authoritarian) or type of policies implemented (partial or complete lockdowns).

Countries that responded successfully to the pandemic all had responsive political leaders. The quicker the leader recognised and responded to coronavirus as a serious threat, the better the management. Second, the presence of trusted medical authorities and strong public health policy has been critical to holding back spread. The third key factor has been strong public awareness and participation. Mutual trust between citizens and the government will promote rationality and voluntary adherence to social distancing and isolation policies.

What about Indonesia?

We are facing the pandemic following an awful early response. As in the United States, Indonesian elites initially downplayed the threat of coronavirus. The shoddy initial response weakened the authority of medical officials. This was seen in the poor coordination and management between institutions, the arrogance of politicians who prioritised vital tests for themselves, and the recent actions of some communities to self-quarantine and prevent outsiders from entering.

Many members of the public have been left not knowing what to do or who to trust. At the same time, the numbers of patients continues to climb, hospitals are increasingly overwhelmed, and medical professionals are putting their lives at risk because of a lack of protective equipment.

With public pressure for a more serious government response growing, President Joko Widodo issued a policy of large scale social restrictions, accompanied by assistance for poor people affected by the economic consequences of the pandemic. Many have continued to call for tighter restrictions on movement.

But as we have seen from the examples of the countries above, lockdowns will not necessarily slow the rate of spread. On the other hand, a more relaxed approach to movement restrictions and social distancing will not necessarily fail. But Indonesia clearly does not have the skills or resources of Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. So what chance does it have to escape the worst effects of the virus?

Indonesia’s greatest asset is its active civil society. It is Indonesia’s civil society that could help to build solidarity following the appalling early response to the virus. But if civil society is to build collective solidarity to respond to the pandemic, three things will be required.

First, Indonesia needs responsive and convincing leadership. At this late stage, the president now has to steel himself to face widespread mistrust in the community, and attempt to prevent this lack of trust from becoming worse. He may need to call on other capable national figures to help him convince the public that Indonesia is able to get through this pandemic. It will not be possible to overcome the crisis if the public remains divided.

Second, to support a responsive leader, Indonesia needs to strengthen its medical authorities. Political decisions on managing the pandemic must be based on sound public health and medical advice. Without strong medical leadership, public health policy can easily become a new playground for unethical business operators or a stage for competing political interests.

Third, to ensure that public health policy is supported by the public, the government must work harder on improving public awareness, participation, and mutual trust between citizens and the government. In this respect, proposals about declaring a civil emergency or martial law must be immediately stopped, as they give a very poor signal to the community. The fact that the debate on martial law has progressed this far indicates that the government does not have confidence that its policies will be followed, and has instead chosen to look to threats and repression.

The coronavirus has already brought panic and horror to Indonesia. Many are dying. There is widespread fear. But Indonesia should not let pessimism about the government’s weak early response detract from clear thinking and dedication to respond to the ongoing threat. The history of humankind shows that determination, knowledge, and humanity, even if it comes late, will ensure that we can make it through this crisis.

This piece was first published in Indonesian in the 4 April edition of Tempo Magazine as “Demokrasi Dalam Melawan Pandemi” and has been republished with permission.