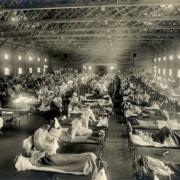

The closure of the fish market has had a major impact on the incomes of many residents of the Kali Adem fishing community. Photo by Tengku Raka.

It is now two months since Indonesia announced its first confirmed cases of Covid-19 on 2 March. The number of cases continues to climb, while the “large-scale social restrictions” (PSBB) implemented in Jakarta since early April are having profound economic and social consequences for residents of the city, especially its poor and marginalised.

One group that has been disproportionately affected is the fishing community of Kali Adem in North Jakarta. Their homes, built on the banks of Muara Angke, have poor sanitation and no access to running water. Even under normal circumstances, they face the near constant threats of flooding and forced eviction.

Despite lacking formal land certificates, the community of Kali Adem have clear legal status and are recognised residents of Jakarta. The community is comprised of 167 families, and 567 individuals, in 18 neighbourhood units (RT). Although they are distributed across several areas, they effectively live in one region: the banks of Muara Angke. The majority work as fishermen or women, but they earn income in a variety of other ways, for example as laundry workers, day labourers, hawkers, security staff, and construction workers.

The combined shocks of Covid-19 and the accompanying social restrictions have had a marked impact on this community. Based on a quick assessment conducted by LBH Masyarakat paralegals, about 85% of 158 Kali Adem residents surveyed said that they had lost income, with most reporting falls of 50% to 75% from normal levels.

The reasons for this are numerous but relate mainly to the closure of the fish market, which has left fishermen and women unable to sell their catch. This has had follow-on effects for local residents who earn a living selling goods and services to fish market customers. Members of the Kali Adem community in more formal work have mostly been ordered to take leave without pay or have lost their jobs completely.

Health impacts

Under Jakarta’s large-scale social restrictions, citizens are required to implement “clean and healthy lifestyle” protocols, which range from regular hand washing and eating a healthy diet, to wearing masks when leaving the home. But how are the Kali Adem community supposed to do that when their right to a clean environment has never been fulfilled?

If members of the Kali Adem community want clean water they have to buy it. If they want to bathe or go to the toilet, they have two options: do it directly in the river, or use a public toilet, usually for a fee. The density of their living arrangements makes social distancing almost impossible. And given that so many have lost their sources of income, it is hard for them to purchase masks.

High density living arrangements make social distancing almost impossible. Photo by Tengku Raka.

If the government is serious about communities implementing clean and healthy lifestyle recommendations, it needs to do more to ensure poor residents have access to clean water and sanitation, for example by setting up washing stations and clean water collection points, or distributing masks and hand sanitiser.

Disorder in delivery of assistance

The national and Jakarta governments have announced support packages, but assistance has been slow to arrive, and there has been poor coordination between levels of government.

The Jakarta government is providing packages of staple goods but many people have missed out because their place of residence does not match government records. In one region of Kali Adem, just 20 families were recorded as being eligible to receive staple goods, while most of the other residents in the area missed out. In any case, the neighbourhood chief held on to the assistance packages anyway, saying that they would only be distributed if residents paid waste collection fees and building taxes. No government regulations allow assistance packages to be held ransom like this.

The second phase of staple goods distribution by the Jakarta government has been delayed while data is validated, because of the large amount of staple goods assistance in the first phase that did not reach intended recipients.

Problems in Kali Adem are amplified by the fact that the fishing community are informal workers, they are not legally recognised as business owners and don’t contribute income tax. This means that they are not covered by the government’s social safety net. For example, Jakarta Governor’s Regulation No. 33 of 2020 on the implementation of social restrictions makes no mention of informal workers, let alone fishing communities, receiving any kind of tax incentives or support. The regulation unfairly favours those in the formal sector.

These problems with social assistance have been compounded by a lack of clear policy measures to support local communities like Kali Adem. The government has yet to provide any assistance that would support the ongoing livelihoods of the fishing community.

Comprehensive and fair social assistance

Kali Adem fishermen and women are highly dependent on the operation of the fish market. But since the implementation of social restrictions, they have not been able to sell their catch as normal. Many other sectors have had to adapt their business practices to social restrictions, the fishing industry could do so too.

Technology-based trading, for example, would allow markets to continue to operate online, and help Kali Adem fishermen and women continue to sell their catch. Likewise, the provision of cold storage facilities would allow fishers to store small stocks of fish intended for sale to small and medium businesses or consumers for sale at a later date.

Unfortunately, the government’s response to the economic impacts of the coronavirus and social distancing has consisted solely of distributing staple goods – it has yet to implement policies like those above, which would go a long way to keeping fishermen and women in work and mitigating the impacts of the pandemic.

The Jakarta government urgently needs to craft better solutions for poor and marginalised Indonesians, like those in Kali Adem, both in the short-term during the crisis phase of the pandemic, and in the long-term, to ensure sustainability of their livelihoods.

There are two things that the government can do. First, it must formulate a coronavirus regulation to ensure the delivery of comprehensive and equitable social assistance to all sectors of the workforce affected by Covid-19, both formal and informal. Second, it must increase the budget for social assistance to increase the quality, coverage and sustainability of assistance. It must go beyond staple goods, and include measures like improvements to sanitation, and targeted policy measures to support livelihoods.

The Jakarta government has done better than most other regional areas in responding to the Covid-19 crisis, but it still has a long way to go to ensure communities like Kali Adem don’t continue to slip through the gaps.