Incumbents enjoy various advantages over their challengers, including the ability to engage in patronage and voter-friendly spending using state resources. Photo by Tim Mann.

On Wednesday, voters in 260 districts and 9 provinces in Indonesia will choose their mayors (bupati and walikota) and governors in local elections known as pilkada. Among the areas electing local leaders are Solo, which in 2010 re-elected a young Joko Widodo as mayor, and Surabaya, where celebrated mayor Tri Rismaharini will seek a second term. Indonesia’s newest province, North Kalimantan, will elect its first governor in its three-year history. In all, just over 100 million Indonesians are registered to vote.

These elections almost didn’t happen. In the final month of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s presidency, lawmakers ruled to return the power to elect mayors and governors to local legislatures. Only a public outcry forced Yudhoyono to use emergency legislation to restore direct local elections.

Underpinning this outcry was a sense that local elections are an important way for Indonesians to hold their mayors and governors to account and for new leaders to emerge. Most of Indonesia’s impressive new leaders, Jokowi included, came to prominence through Indonesia’s two previous rounds of direct local elections, held from 2005-2008 and 2010-2014. Such leaders include Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), Bandung Mayor Ridwan Kamil, Surabaya Mayor Tri Rismaharini, Central Java Governor Ganjar Pranowo, and Bogor Mayor Bima Arya (although his star has recently dimmed).

In reality, direct local elections pose a difficult challenge for non-incumbents seeking office. [In Indonesia governors and mayors run for office on a two-person ticket with a deputy. By incumbent, we mean either the governor/mayor or their deputy seeking re-election.]

According to a team of World Bank economists, incumbents won 53 per cent of the first 173 pilkada held starting in 2005. All of the districts and provinces electing leaders on Wednesday held their most recent election in 2010-2011. In those elections, incumbents maintained their success rate, winning 57 per cent of 224 pilkada for which data is available to the authors.* These figures actually understate the incumbency success rate, because they include pilkada where no incumbent candidates ran.

Where there was at least one incumbent candidate in 2010-2011, incumbents in fact won 67 per cent of the 190 district pilkada and 71 per cent of the seven provincial pilkada. Given their high success rate, it’s no surprise that at least one incumbent candidate contests most pilkada (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The majority of pilkada races have at least one incumbent candidate.

Source: Indonesian Ministry of Home Affairs, Indonesian General Election Commission, and media sources. Note: The data set used in this article includes data from all nine provinces and 230 (of the 260) districts holding elections on 9 December 2015. The 2010-2011 election results were missing from six districts.

Incumbents enjoy various advantages over their challengers. Beyond their track record and name recognition, they can also engage in patronage and voter-friendly spending using state resources in the lead-up to an election. In many areas, incumbents also attempt to mobilise the bureaucracy to secure their re-election.

So strong is this advantage that for the elections on Wednesday, political parties tried to exploit a legal loophole to undermine strong incumbents. Lawmakers had ruled that elections would only be held if two or more candidate pairs were running, so challengers in seven districts attempted to prevent elections going ahead by leaving the incumbent to run unopposed. Their hope was that without an opponent, the General Election Commission (KPU) would be forced to delay the election until 2017.

The Constitutional Court put paid to this tactic by deciding voters will be asked simply to “agree” or “disagree” with the unopposed incumbents governing for a second term. Only if a majority disagrees will a fresh election be held in 2017. In a recent Talking Indonesia podcast, elections expert Titi Anggraini predicted no candidate would face the ignominy of losing an unopposed election, as Indonesian voters would find the “disagree” option to be too negative.

Where incumbents ran in 2010-2011, mayors and governors were more successful as candidates than deputy mayors and deputy governors seeking to make the step up. In half of the elections won by incumbents, the incumbent mayor or governor gained re-election alongside a new running mate.

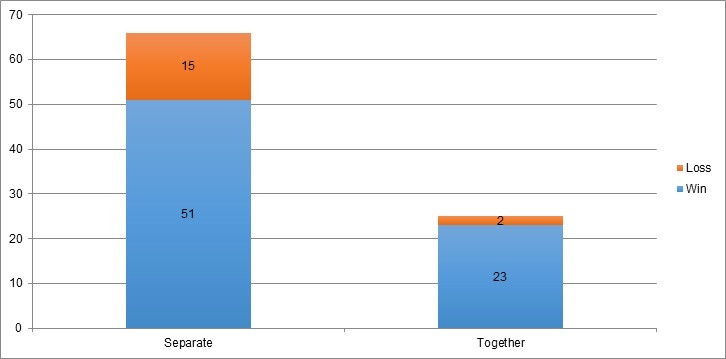

Figure 2: Mayors and governors are more successful as candidates than deputies seeking to make the step up (2010-2011).

Source: Indonesian Ministry of Home Affairs, Indonesian General Election Commission, and media sources. Note: The data used in this article includes data from all nine provinces and 230 (of the 260) districts holding elections on 9 December 2015. The 2010-2011 election results were missing from six districts.

Only 16 per cent of incumbents who won a second term were mayors/governors and their deputies seeking re-election together. This low figure reflects the fact that local leaders and their deputies usually go their separate ways after one term. Incumbent mayors and governors only sought re-election with the same deputies in 27 per cent of instances where both were candidates (25 of 91 elections).

When they did stick together, incumbent pairs were almost unbeatable, winning 23 of 25 elections (92 per cent). By contrast, when incumbent mayors and governors ran against their deputies, they reduce both their chances – an incumbent candidate only won in 77 per cent of such elections. If either wins, mayors and governors usually out-compete their deputies, winning 76 per cent of such races (39 of 51 elections).

Figure 3: Incumbent pairs were much more successful in re-election campaigns when they ran together in 2010-2011.

Source: Indonesian Ministry of Home Affairs, Indonesian General Election Commission, and media sources. Note: The data set used in this article includes data from all nine provinces and 230 (of the 260) districts holding elections on 9 December 2015. The 2010-2011 election results were missing from six districts.

Why do deputies choose to split when doing so significantly reduces their chances of winning? Beyond simple individual ambition, deputies reportedly are often motivated to run because they are not assigned any meaningful areas of responsibility. They also often come from different political parties, who may want them to seek the top job.

Incumbent pairs may have learned their lesson, at least at district level. In 2015, incumbent pairs stuck together in 47 per cent of the 83 races where both a mayor and his or her deputy are running. Deputy governors are bolder – none are seeking re-election with the incumbent governor.

Of course, just because incumbents dominate local elections does not mean new style leaders cannot emerge. Jokowi was a little known figure nationally when he ran for re-election in Solo in 2010, winning with 90 per cent of the vote. Four years later he was president, having scored a rare victory against an incumbent governor in Jakarta in 2012 along the way. It is not beyond question that Indonesia’s next president could be contesting a pilkada tomorrow, even perhaps running as an incumbent.

* The data set used in this article includes data from all nine provinces and 230 (of the 260) districts holding elections on 9 December 2015. The 2010-2011 election results were missing from six districts. Thanks to Tim Mann for his research assistance in compiling this data set.