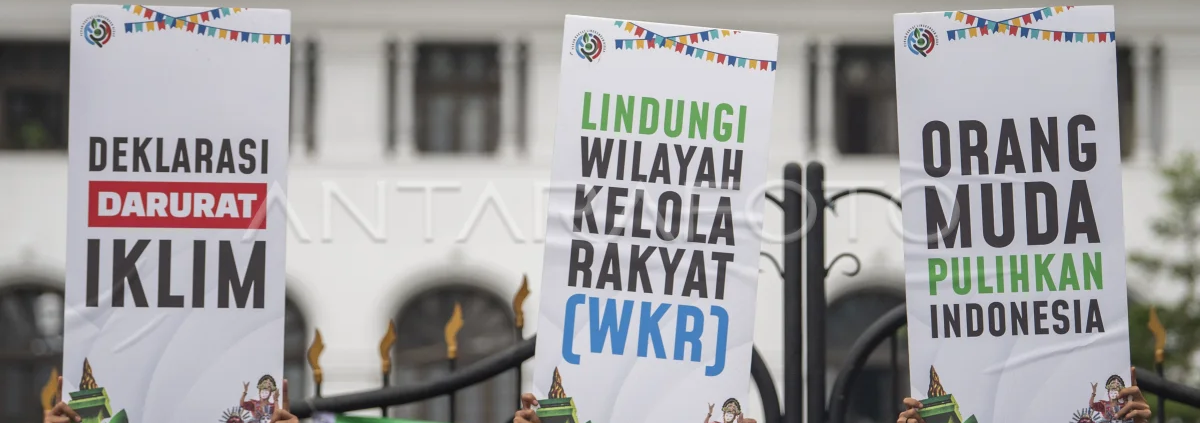

Protestors call for climate action at the West Java Indonesian Forum for the Environment (WALHI) in June. Photo by M Agung Rajasa for Antara.

In recent years, many studies conducted by human rights organisations and think tanks have found civic space in Indonesia is shrinking, at least in the areas of freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association.

There has been an increase in cases criminalising human rights defenders and government critics through defamation cases, harassment, intimidation and attacks against political dissidents, both physically and online.

In 2021, one of the most powerful ministers in the country, Luhut Panjaitan, even threatened Greenpeace Indonesia and other NGOs by saying the government would ‘audit’ any NGO that provided false information. This came after Greenpeace countered claims in President Joko Widodo’s COP26 speech about deforestation rates in Indonesia.

During the Covid-19 pandemic there were also increased reports of online surveillance by cyber operatives linked to government officials and politicians. They were accused of harassing, intimidating and attacking critics of key government policies, like its policy of suppressing information about human rights violation in Papua.

In recent years, there have even been suspicious deaths of environmental activists and human rights defenders who were outspoken against state and non-state actors.

These anecdotal accounts all paint a bleak picture of a civic space in decline.

What is the civic space and why does it matter?

Civic space is defined by three indicators:

- existing institutional channels, including laws and procedures, and the possibilities for contestation they offer;

- discourses, including the power to label and frame; and

- the capacity to maintain and create new spaces.

These all suggest that civic spaces are determined, first and foremost, by state power. However, the sustainability of civic spaces is also affected by the internal resilience of existing Civil Society Organisations (CSOs, including NGOs) that form the civic ecosystem.

In Indonesia, civic space is comprised of many CSOs that conduct research and advocacy across a range of different fields, especially rights and democratisation, anti-corruption, anti-discrimination, economic empowerment and promoting the rule of law. These CSOs play an important role in Indonesian society by safeguarding human rights, freedom of opinion and expression and freedom of assembly, but they also feel they are now under threat.

What does Indonesia’s civic space look like on the ground?

To acquire a more comprehensive understanding of Indonesia’s civic space, we surveyed 62 CSO leaders across Indonesia in October 2022. Interviews and a workshop were held to gain deeper insights on their experiences.

The findings of our research were clear – Indonesia’s civic space is shrinking.

CSOs are facing a range of pressures and obstacles that are making it harder to get established and operate in Indonesia. Laws and regulations, and an increasing number of bureaucratic procedures, are hindering the delivery of new and existing services and initiatives.

CSOs report a variety of direct threats to their welfare, including the receipt of threatening messages, hacking of private data, property damage and physical violence. Not all endure threats and violence, but most feel that at least one aspect of their work poses risks. This applies even to CSOs that simply do charity work.

Threats were reported across different fields and geographies, although all CSOs operating in Papua – no matter what field – are more prone to the risk of violence.

It is also clear that social media has become a crucial terrain for state control and influence, with CSOs reporting that their civil liberties are being suppressed in the digital realm. For example, doxing and cyber surveillance by state officials and state-sponsored influencers, have been directed at government critics. The most blatant cyber attack occurred against activists from the Student Political Front (BPP), when their personal data, including home addresses, were exposed online.

Threats are exacerbated by political elites employing inflammatory rhetoric, for example applying labels like “foreign proxy”, which tarnishes the legitimacy of CSO work.

To mitigate the risk of threats and violence, smaller CSOs often rely on other, more established, organisations focused on protecting human rights, like the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence (KontraS) and the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI). This means legal advocacy work has now become crucial for grassroots groups and the advocates themselves.

This all comes at a time when the commitment of donors is wavering. Over the last decade, many donors have reduced their support to human rights organisations in Indonesia, especially in the area of civil liberties.

Where to from here?

Despite facing oppression, terror and violence, Indonesian CSOs are resilient – continuing their programs and expanding their networks despite being under immense external stress.

Human rights defenders and activists often put their work ahead of personal risks. But this culture of self-sacrifice and heroism can cloud the discussion about the need for human rights defenders to protect the civic space.

If Indonesia is to reverse the tide of a shrinking civic space, CSOs and activists – from across different fields and geographies – will need to work together to advocate for safe work conditions and their rights to freedom of expression and assembly.

It will also require solidarity from donors. At the beginning of the current administration, many CSO activists and donor agencies welcomed the election of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, seeing him as a supporter of civil society organisations and human rights ideals.

But nearly a decade on, studies like ours confirm that democracy and the civic space are clearly in decline under Jokowi. With Indonesia going to the polls again in 2024, now is the time for CSOs and activists to come together and start actively reclaiming Indonesia’s civic space.