One of the subjects of The Act of Living exhibition, Milah was 13 when she was sent to prison for 14 years, for dancing to a song associated with communism. Photo by Anne-Cecile Esteve for AJAR.

It is 50 years today since the beginning of the brutal repression of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and organisations on the political left. The army and anti-communist vigilantes killed at least 500,000 Indonesians. Hundreds of thousands more were subject to torture, rape, imprisonment without trial – and then societal stigmatization on release.

Those targeted in the violence were not the only ones to feel its effects. Across the generations, children and grandchildren suffered grief from the loss of a parent or grandparent, whether permanently or for the period of their imprisonment. They may have been young at the time of the violence (or even unborn) but many children and grandchildren have continued to feel the weight of the events of 1965 through what Marianne Hirsch describes as “postmemory”.

Postmemory is “the relationship that the generation after those who witnessed cultural or collective trauma bears to the experiences of those who came before, experiences that they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images, and behaviours among which they grew up.” Hirsch explains that “these experiences were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right.”

Given the scale of the violence, it is likely that even if people from the second and third generations after the violence did not witness it, they may have heard stories about family or community members disappearing, or about killings and other episodes of violence in their local neighbourhoods. Given the climate of intense anti-communism in Indonesia, many may have responded by believing the violence was justified – the narrative that has been promoted for so long.

There are others, however, who have had cause to reconsider these events. Based on either direct experience or empathy with those who suffered, many people from the second and third generations are now working with survivors to address the legacy of 1965.

After 17 years of fighting for justice for survivors there have been very few justice outcomes. Whenever survivors seem close to achieving some form of formal recognition of their suffering, such as the proposed presidential apology from Suslio Bambang Yudhoyono in 2012, or the recently rumoured Joko Widodo apology, anti-communists counter them by arguing that the survivors are not victims and do not deserve justice.

Some activists have therefore turned to cultural initiatives as a way of trying to crack the resilience of anti-communist versions of history. They are now working together with survivors on cultural projects that present history in a new way, broaden community knowledge about the violence, and create greater compassion for survivors.

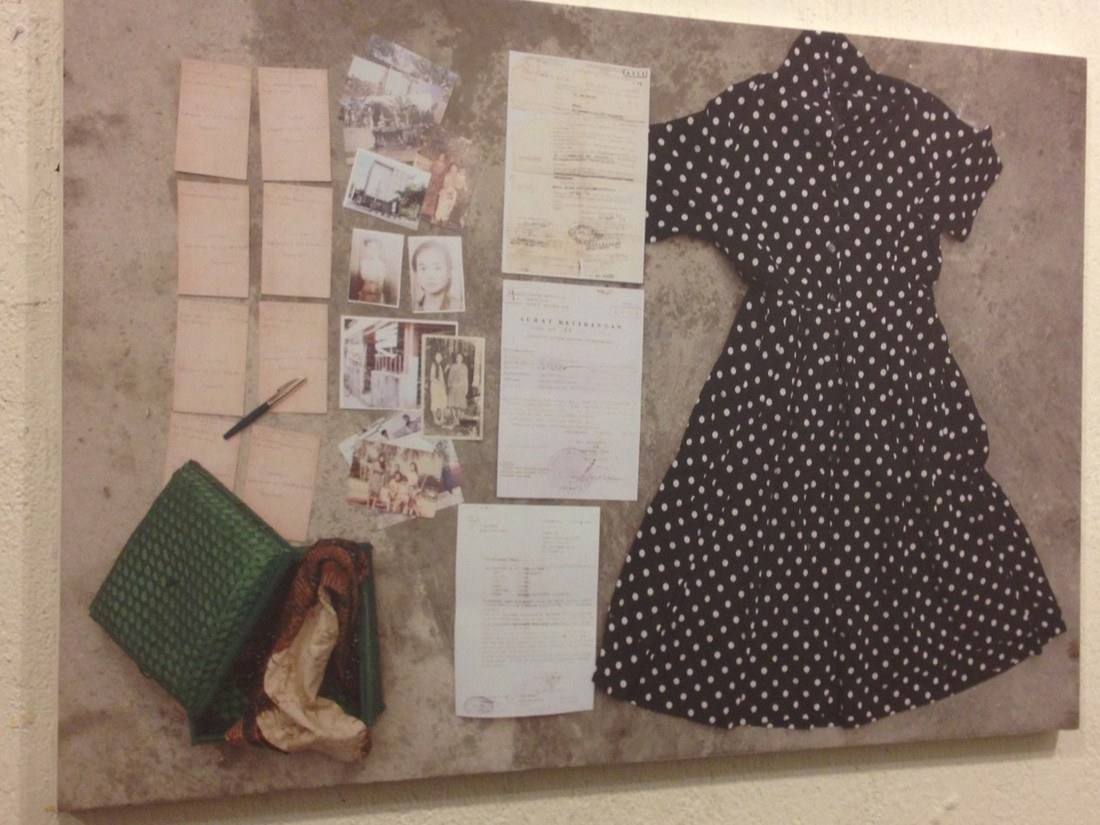

In 2013, for example, the Jakarta-based human rights organisation Asia Justice and Rights (AJAR) began participatory research into women’s experiences of violence and ongoing discrimination. AJAR activists Galuh Wandita and Tati Krisnawati were too young to have lived through 1965 but they believe it is important to address the legacies of this violence. Working with networks of organisations throughout Indonesia that support survivors of the 1965 violence, AJAR invited 27 women to participate in the project. The women’s experiences were presented in an exhibition featuring photographs of survivors and memory boxes. They included objects from their time in detention, such as clothing, letters of release, and correspondence with family.

The exhibition, The Act of Living, plays on the title of the acclaimed film, The Act of Killing, and emphasises how women have lived with the complete impunity of the perpetrators of the 1965 violence, as shown in that film. The demands of women survivors for recognition and justice are presented alongside their photographs. This work has now been compiled in a book: Surviving on their own: Women’s experiences of War, Peace and Impunity, which highlights gender-specific strategies for survival and empowerment, and a documentary film.

Memory boxes displayed in the Act of Living exhibition feature clothing and correspondence from the women’s time in prison. Photo by Katharine McGregor.

For AJAR activists, it is important to address 1965 because of its contribution to an ongoing culture of impunity in Indonesia. This project also emphasizes the enduring afterlife of this violence for these women.

Taman 65, a community dedicated to addressing the broad social and political legacies of 1965, is another group that has engaged in intergenerational projects to present an alternative narrative of the violence. Members of the community, which is based in Kesiman, Bali, focus on trying to overcome the stigmatisation of survivors and to foster respect for the dignity of affected communities.

Taman 65 in August launched an album, Prison Songs: Songs That Were Silenced. Most of this music covers the experiences of inmates in Pekambingan prison in Bali, which has now been demolished and replaced with a shopping complex. Despite the physical destruction of this site of memory, the experience of imprisonment lives on in the songs and the accompanying book. The songs are evocative and melancholic. They invite listeners to empathize with those targeted in the violence and with those around them who lost loved ones.

In one song, Si Buyung (Dear Child), R Amiruddin Tjiptaprawira describes a child born into conditions of misery with a father who could not hear its cries because he was in jail. The father recognises his child will face a life of pain, but calls upon the child to grow up fast and become a “hero of the nation”.

Roro Saswita, a Taman 65 researcher, explained that the idea for the album came from the fact that former political prisoners often sang songs from the past when being interviewed by researchers. Taman 65 decided that recording these songs could connect younger generations to the past. The songs were adapted, performed and recorded by young Indonesian musicians, such as “Jerinx” or I Gede Ari Astina, the renowned drummer of the band Superman is Dead, members of the band Navicula, and musicians from Taman 65.

Kamala Chandrakirana, the coordinator of the Coalition for Truth and Justice (KKPK), which supported the album launch, says the initiative is important because it provides a new way of approaching the legacy of 1965 – an alternative to just another human rights report.

Common to both these cultural memory projects is collaboration across the generations. Survivors of the violence have played a crucial role in framing and transmitting their experiences to the younger generations. After 50 years, with many of the perpetrators dead or dying and prospects for state-led reconciliation slim, cultural initiatives are a critical means to recognise the impact the violence continues to have on victims and their families.

Both the Act of Living project and the Prison Songs project will be featured in the Ubud Writers Festival in October.