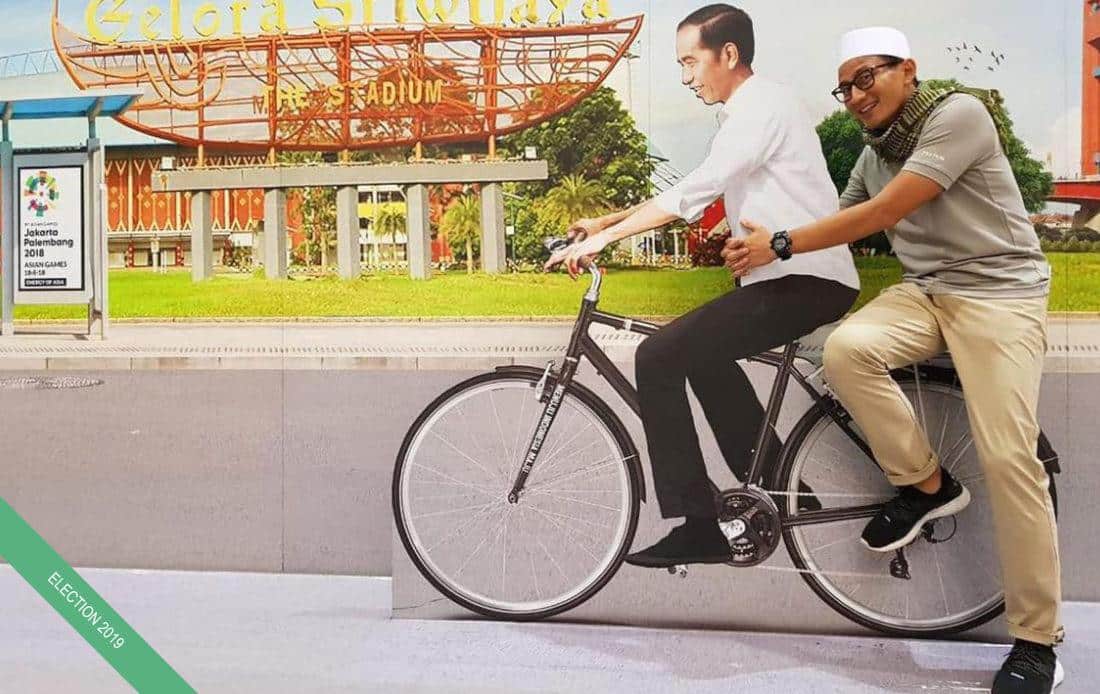

Many observers have speculated that Sandiaga Uno is using the 2019 campaign as a trial run for 2024. Photo by @sandiuno/Instagram.

Multi-millionaire businessman Sandiaga (“Sandi”) Salahuddin Uno has been the surprise star of the 2019 presidential election campaign. The 49-year-old is running for vice president on Prabowo Subianto’s ticket, although he has little in common with the former military general.

There are even greater differences between Sandi and his vice-presidential rival, 76-year-old conservative Muslim cleric, Ma’ruf Amin. In fact, Sandi may have more in common with President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo than any of the other leadership contenders in 2019. Like Jokowi, Sandi appears to genuinely enjoy meeting people and both of them enjoy sport. Sandi cheekily challenged Jokowi to a basketball match, Sandi’s preferred sport, an offer that Jokowi has not taken up. The two could even have a joint birthday party: Jokowi was born on 21 June 1961 and Sandi on 28 June 1969.

Like Jokowi, Sandi is from a business background and entered the national stage after a short period in the government of Jakarta. But Sandi is a political newbie, having served less than a year as deputy to Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan, while Jokowi made his name as the mayor of his hometown, Solo, Central Java, where he served for nearly a decade before becoming Jakarta governor in 2012 and then president in 2014.

But their vast differences in wealth mean Sandi and Jokowi also have vastly different approaches to politics. Jokowi has had to make do with a borrowed political party (Megawati Soekarnoputri’s Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P)) because he doesn’t have his own political vehicle. By contrast, Sandi’s ascent to politics is closer to the familiar oligarchic pattern common to Indonesian politics. Although Sandi also doesn’t have his own party, and resigned from Gerindra when he became a vice-presidential candidate, he is rich enough that observers have speculated that Prabowo might “sell” Sandi the party if they lose the election on 17 April.

Sandi, the younger of two siblings, was born in Rumbai, Pekanbaru, Riau, where Sandi’s father, Razif Halik (Henk) Uno, worked as an engineer for Caltex. The family later moved to Jakarta, where Sandi grew up. His father is from Gorontalo nobility and trained in Bogor, where he met Sandi’s mother, Rachimini Rachman (Mien Uno). Mien is from Indramayu, West Java, and initially went to Bogor for teacher training. In Riau, Mien taught briefly in a kindergarten, but in Jakarta became known as a beauty and etiquette specialist. In summary, Sandi came from a well-to-do family, in contrast to Jokowi’s humble origins.

Sandi attended a Protestant primary school, a state junior high school and a Catholic senior high school. He then studied accountancy at Wichita State University in Kansas and George Washington University in Washington DC, United States.

Like Jokowi, Sandi married his childhood sweetheart. He and Nur Asia now have three children (as do Jokowi and Iriana). Like Jokowi, Sandi is Muslim but not exclusive in his social and business contacts. Religion is not a key factor in his political platform. Nevertheless, commentators have noted that he has made frequent visits to Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) and has been happy to be labelled a ‘santri’ – aware that he and Prabowo are backed by conservative Muslims.

In fact, Sandi’s emphasis on his faith had begun before his run for the vice presidency. In his autobiography (2014), Sandi devotes a section to his increasing piety, particularly under the influence of Nur Asia, whose background is much more pious. He has also been involved in ICMI, the Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals Association. On the other hand, there have been comments that even when Sandi visits religious groups, his speeches are less about religion than his key focus: the economy.

Both Sandi and Jokowi became involved in local and national politics after periods in community and business organisations. Jokowi began by chairing the local branch of the Indonesian Furniture Entrepreneur’s Association (Asmindo) in 2002. Sandi, meanwhile, was treasurer of PPSK, the Catholic Students Organisation, while still at school. Later, he took on the role of treasurer of ICMI, then he became head of first HIMPI (Indonesian Young Businesspeople’s Association) and Kadin (the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry). In both cases, these organisations served as training grounds for politics.

Jokowi had reasonable success in his wood and furniture business, whereas Sandi became a highly successful entrepreneur as a relatively young man. Sandi’s reported wealth of US$349 million at the beginning of the campaign was roughly 100 times that of Jokowi, although Sandi has said that he has now spent about a third of his wealth, around US$100 million, on the campaign.

After graduating, Sandi worked for Bank Summa, where he met the Soeryadjaya family. Through Bank Summa, he received a scholarship to study at George Washington University, and in 1995 was appointed executive vice president of NTI Resources Calgary, Canada (a company with Soeryadjaya connections). When the Asian Financial Crisis hit in 1997, Sandi lost his job and returned home.

Back in Indonesia, in 1998, he co-founded PT Recapital Advisors with his high school friend, Rosan Perkasa Roeslani, and Saratoga Capital with Edwin Soeryadjaya, the son of William Soeryajaya.

These companies have been involved in a wide range of industries, including energy (particularly coal mining and electricity) and infrastructure (such as water and toll roads). Notably, the group owned Aetra, the private firm responsible for operating tap water in the eastern parts of Jakarta. Sandi divested himself of his Aetra shares in 2017 “to avoid conflicts of interest”.

By 2009, Forbes magazine estimated Sandi had become the 29th richest man in Indonesia. In 2016, Sandi’s name was listed in the Panama Papers, among many other high-profile figures who used off-shore companies in tax havens. At the time, Sandi said he needed to maintain off-shore businesses because Indonesia did not provide a conducive climate for investors, which the tax haven countries were able to offer. At the same time, however, he claimed that his company had always fulfilled its tax responsibilities. Like Jokowi, Sandi says that he has sold all his shares in his companies now that he is running for office.

While mayor of Solo, Jokowi began his famous impromptu visits (blusukan), to catch officials engaging in corruption, earning him a clean image. Although there have been rumours of corruption surrounding Sandi, they have never been substantiated. In the 2019 campaign, Jokowi’s blusukan visits appear to have fallen by the wayside and he has favoured a more conventional “presidential” campaign. However, Sandi has taken up the blusukan approach with gusto – he is estimated to have made more than 1,500 visits to communities over the course of his campaign.

Some of Sandi’s attempts to create press when he meets “the people” have, unfortunately, not gone to plan. In February, Sandi met a devastated onion farmer in Brebes, Central Java, who was crying poor following a slump in onion prices. The farmer turned out to be a former commissioner of the General Elections Commission (KPU) in Brebes. Last week the farmer was arrested for physically abusing a 71-year old man who was repairing a Jokowi campaign flag on the side of the road.

Similarly, Sandi was mocked on social media after he met a mud-splattered victim of flooding in Makassar, South Sulawesi, who appeared to have a completely clean back, prompting questions about how he got dirty in the first place.

These unfortunate events have been derided with the hashtag sandiwara (theatrical performance) – a play on Sandi’s name that highlighted that these were staged events. Things got worse, when Sandi’s mother leaped to his defence, earning him the reputation of being a “mummy’s boy”.

Given Sandi’s business background, it is not surprising that his campaign has focused on the economy. He has argued against making unrealistic predictions of growth (stressing 5-6 per cent is ample) and prioritised job creation, empowering small and medium enterprises and fostering entrepreneurship.

He has also pushed for revitalisation of the agriculture industry. Although he is supportive of food self-sufficiency, he has quite a pragmatic approach to trade, saying that the emphasis should be on keeping food prices stable. At times, this puts him at odds with the nationalistic posturing of his running mate, Prabowo.

If the polls are correct and Jokowi wins, that is unlikely to end Sandi’s political ambitions. This election campaign might turn out to be just a training ground for Sandi. Many think he may be considering a run for president in 2024, when Jokowi will be barred by the Constitution’s two-term limit on presidents.

This article was co-published with Election Watch.