The contestation between city and kampung is a prominent part of urban life in Bandung. Photo by James Connor.

When Bandung Mayor Ridwan Kamil came to power in 2013, there was an emerging consensus that he had inherited a city in declining health. Rapid urbanisation and poor attention to public infrastructure had led to chronic traffic congestion, environmental pollution and social inequality. Many complained that the so-called Paris of Java had lost much of its charm.

The mayor promised to revitalise the city, boost infrastructure spending and offer a new style of clean, responsive and consultative leadership. His government released a Bandung Detailed Spatial Plan, and a number of development projects are in the pipeline, including a cable car and monorail, new urban parks, and plans to modernise traditional markets. Although almost everyone agrees that new transport infrastructure and green space are desperately needed in Bandung, the government’s ambitious plans are running headlong into the informal activities that have shaped the city over many years.

Informal development practices have allowed low-income families excluded from the housing market to incrementally build homes. Likewise, for many low-income Indonesians, informal trading on the street or in markets is a way to enter the wage market and can be a source of upward mobility through access to education. To provide another example, Bandung (like most Indonesian cities) is highly dependent on informal recycling practices. Not only do these practices reduce the amount of waste sent to landfill, but they can also provide income for citizens on the margins of the economy. Informality also underpins the lives of the burgeoning middle class, who rely on a complex network of informal activities that provide food, transport, waste management, culture and entertainment.

Most “informal” parts of the city are actually highly organised. Urban villages (or kampung) have strong governance structures in the form of neighbourhood (RT) and community (RW) associations. Many urban villages have initiated activities in areas such as family planning, microfinance, and social security. Despite the density and lack of public space that characterises kampung life, there are social advantages, too. Pedestrian laneways function as focal points and create opportunities for serendipitous meetings. Strong social cohesion means that when the state doesn’t do its job, the community pulls together, for example by cleaning waterways after flooding, improving roads or managing waste.

Although labour surveys suggest that up to 70 per cent Indonesian workers are employed in the informal sector, the benefits of informality aren’t always recognised by the government. Most elements of Bandung’s Detailed Spatial Plan favour the elite, and limit the participation of the urban majority, the kampung residents, in the life of the city. The informal aspects of life in Bandung are seen as “illegal”, “unsafe” and “undesirable” – they are the antithesis to the development of a modern city. Tellingly, one of Ridwan Kamil’s first moves as mayor was to ban food carts, or kaki lima, from main thoroughfares.

In a series of projects conducted during November 2015, students from the Melbourne School of Design (MSD) worked with students from the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) to look at approaches to designing with urban informality. The joint studio focused on sites surrounding Bandung’s constantly transforming commercial street, Jalan Dago. Designated as a “Travelopolis” in the Bandung Detailed Spatial Plan, there are plans to revamp the Jalan Dago area to attract more international tourists, with a focus on colonial architecture, restaurants and cafes, shopping, and urban gardens.

One site examined was the Lebak Siliwangi kampung, a densely settled area on the banks of the Cikapundung River. Located about 5km from the Bandung city centre, the kampung sits between ITB and the famous shopping street Jalan Cihampelas. The kampung is home to many residents employed in the thriving informal economy that caters to the needs of students and tourists who frequent the area.

But the kampung is under threat from the government’s plans to redevelop the site. Plans include banning development within 10-15m of the river’s edge, and demolishing illegal dwellings and replacing them with high-density residential apartments and large areas of public space along the riverbank. Residents who live “informally” will be evicted and the new public spaces will likely be inaccessible to street vendors. These plans thus ignore the inherent value of the current kampung: the human scale, the opportunities for micro-economic activities, the functional variation, the diversified public spaces and overall flexibility.

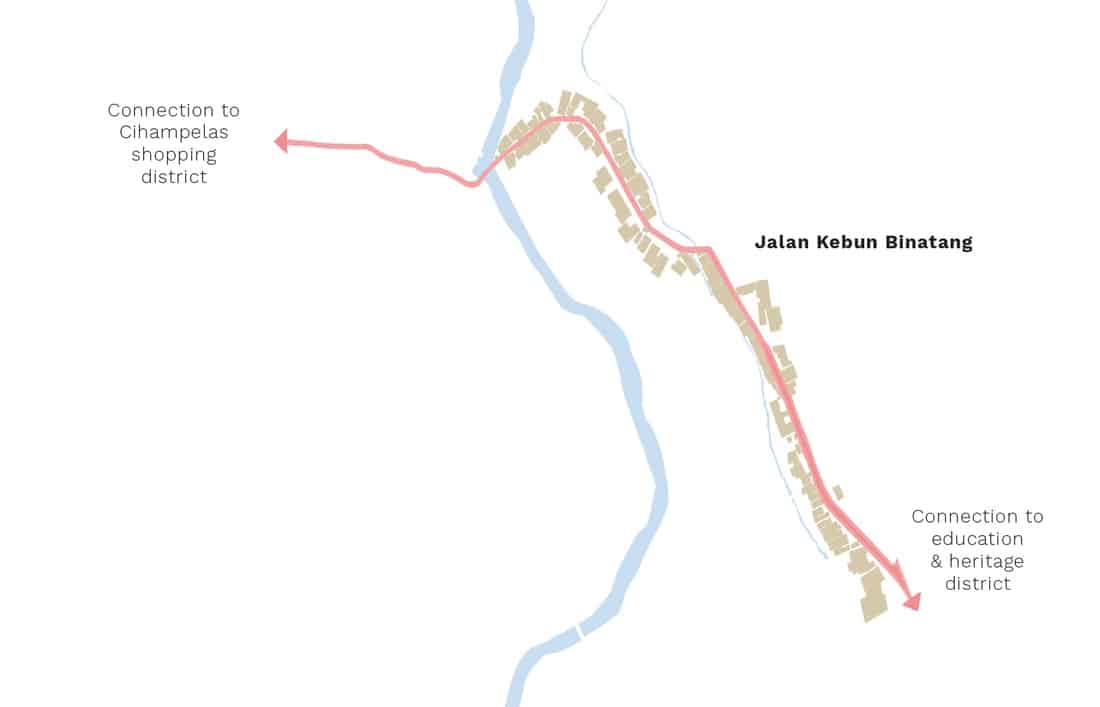

Ridwan Kamil’s modern dreams for the kampung are evident in the planned cable car, known as the Bandung Sky Bridge, which will connect a carpark on one side of the Cikapundung River (at Babakan Siliwangi Hill) to a shopping mall on the other, running over the top of one of the main streets of the kampung, Jalan Kebun Binatang. Construction of the cable car would mean less opportunity for informal vendors, as potential customers are ferried straight from car to mall. Additionally, the pylons used to support the cable car would destroy the urban form and street life of Jalan Kebun Binatang.

The joint MSD-ITB studio suggested alternative models to development in the kampung, taking a more nuanced approach to informality, and recognising the benefits of the formal and informal sectors working together. Students have proposed that the cable car (which is yet to be approved by West Java Governor Ahmad Heryawan) be abandoned and that instead, citizens and government work together to create a new plan for the area, one where tourists walk through the kampung, rather than above it.

A reimagined Jalan Kebun Binatang could provide opportunities for everyone to experience the welcoming urban fabric of the kampung. Such a proposal could give tourists a dynamic experience en route to the mall, and provide the local community with a means of gaining economic advantage from Bandung’s growing tourism industry.

Few doubt that Ridwan Kamil is a passionate leader with a strong vision for his city. But there are grumbles that he is too focused on the concerns of the middle class. Residents complain that community involvement in urban decision-making has been largely tokenistic. The joint studio suggested restructuring the current planning mechanisms to embrace the already strong kampung governance system, and generating community-developed design guidelines that would act as a localised control on development in the area. These approaches focused on community stakeholders and professionals working together to ensure that local residents – as well as tourists and middle-class residents – will benefit from future development. Students envision that the Jalan Kebun Binatang project could operate as a pilot project to demonstrate the benefits of inclusive development. If it proved successful, the same process could be rolled out across other kampung.

Bandung does not need to follow in the footsteps of other Asian cities, which are beginning to see the downside of erasing informality. The Singapore government, for example, has recently called for the reintroduction of “kampung spirit” in the city. Bandung is a vibrant and diverse city with an urban fabric that generates plenty of spirit. Urban development must recognise this as the asset that it is. An approach to development that values informality will take commitment, flexibility and time but it will ensure a more inclusive, resilient and prosperous future for all Bandung residents.

An exhibition of the results of the collaboration between the Melbourne School of Design and Bandung Institute of Technology, The Informal City, will be displayed in the atrium (Level 1 East side) of the Melbourne School of Design until midday 3 March 2016. The travelling studio was coordinated by Dr. Sidh Sintusingha and Dr. Amanda Achmadi of Melbourne School of Design.