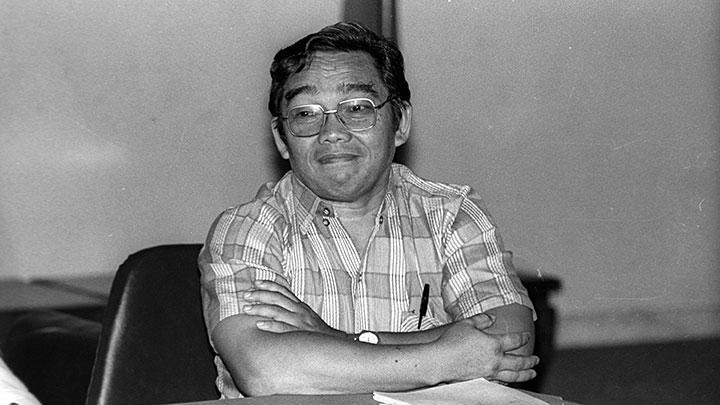

Photo by Tempo.

When the news finally came that former State Secretary Djohan Effendi had died in Geelong on 17 November, few who knew him were surprised. Pak Djohan had a long struggle with illness. It was this illness that motivated him to finish his final work in 2012, “Messages from the Qur’an” (Pesan-Pesan Al Quran). But although we had some time to prepare for his passing, it still hurts to know that he has left us.

With several of his other students, I met him every time he returned to Indonesia from Australia. Although he was clearly unwell, he was otherwise little changed from when we first met him three decades earlier: a spirited debater of ideas – particularly pluralism and how it could be promoted. In his later years, he was not always able to argue his points directly, but his gaze remained sharp and his movements determined. Djohan might have been a man of few words, but his incorruptible mind was never idle.

This principled character is what we will miss most about Djohan. Not only did he preach the importance of openness and mutual understanding in the practice of religion but he was an active defender of religious minorities, including so-called “deviant sects”. When the government debated disbanding the Ahmadiyah community in 2008, he exploded: “So what is the minister of religious affairs going to do? Expel the Ahmadiyah community from the country, put them in prison, or in a mass grave?”

His impassioned defence of the Ahmadiyah often saw him labelled by conservative groups as an Ahmadiyah follower himself, or “an accomplice of the Jews”. Fortunately Djohan was the kind of person who did not dwell on others’ opinions of him. He was resolute in his defence of the Ahmadiyah community, because he believed that was what Islam instructed: there is no compulsion in religion, and the right to choose one’s own religion must be respected. In fact, the attacks he faced only made him more militant in his efforts to challenge religious exclusivism.

Djohan’s defence of religious minorities often saw him compared to Nurcholish Madjid (Cak Nur) and former President Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur). But apart from the fact that he wasn’t Javanese like his two friends and contemporaries, he was a sometimes-reticent figure and didn’t have the same gift for rhetorical flair. This meant he was never as well known as Cak Nur or Gus Dur. But knowing Djohan I don’t think this concerned him much.

While he was sometimes reluctant to take centre stage, he played a crucial role behind the scenes. A close friend of Islamic thinker and reformer Ahmad Wahib, he contributed a great service to Indonesian Islamic scholarship in recording Wahib’s ideas and thoughts in “Restlessness of Islamic Thought: The Diary of Ahmad Wahib” (Pergolakan Pemikiran Islam: Catatan Harian Ahmad Wahib) (1981). This book continues to be a crucial reference and source of inspiration for critical religious studies in Indonesia.

When assisting former Minister of Religious Affairs Mukti Ali in the early 1970s, he pioneered interfaith dialogue in Indonesia, a movement that continues to grow. And as the head of the Centre for Research and Development at the Department of Religious Affairs, he helped to foster a tradition of social research that had previously been lacking.

Another of Djohan’s great contributions was his activism. He was involved in the establishment of the Institute for Interfaith Dialogue (Interfidei) and the Indonesian Conference on Religion and Peace (ICRP), two of the most prominent civil society organisations working on religious tolerance in Indonesia. He also understood the importance of leadership transition in a way that neither Gus Dur nor Cak Nur did. He made an effort to nurture young scholars, holding study groups in his home, lending books, and offering to edit or provide feedback on young scholars’ articles (including one of my own). I know many friends with fond memories of the guidance and mentorship Djohan provided.

Aside from this, Djohan was a great Sufi who never acknowledged he was a Sufi, let alone preached it. His frugal nature was legendary. He was a fine example of the difference between living a simple life and living in poverty – an example that many contemporary activists could live by.

I’m convinced it was this asceticism that allowed him to remain independent when dealing with those in power. Because the authorities needed him and not the other way around, any interactions occurred on his terms. This was the case when Djohan served as speechwriter for President Soeharto from 1978-1995. Djohan wrote whatever he thought was important, it was up to Soeharto whether he wanted to deliver the speech as written or not.

We remain in debt to Djohan for these and many other lessons. Rest in peace, Pak Djohan.

This article was originally published in Indonesian in Tempo Magazine.