Jonru is one of the most prominent personalities on Indonesian social media, with almost 1.5 million followers on Facebook and nearly 100,000 followers on Twitter. Photo by Reno Esnir for Antara.

Blogger, social media star and provocateur Jonru is in the headlines again but this time his inflammatory social media posts look to have finally got the better of him. On 29 September he was arrested and detained as a suspect for inciting hatred against ethnic, religious, racial or other groups in society, something many had expected for some time.

Lawyers Muannas Al-Aidid and Muhamad Zakir Rasyidin filed separate complaints to police on 31 August and 4 September over one of Jonru’s posts on social media, in which he said that President Joko Widodo was the only Indonesian president whose parents’ backgrounds were unclear. Jonru had previously admitted on a television talk show that he wrote the post but said he had not wanted to offend the president. Jakarta Metropolitan Police nonetheless charged him under the Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) Law, and he could face up to six years in prison if found guilty.

Who is Jonru, and how did he become such an influential figure in Indonesian politics?

Jonru was born Jon Riah Ukur Ginting in 1970 to a Batak family in North Sumatra. In just a few years, he has become one of the most prominent personalities on Indonesian social media, amassing almost 1.5 million followers on Facebook, nearly 100,000 on Twitter and more than 60,000 on Instagram.

Until 2014, Jonru, an accountant by training, was a largely unknown content writer, who developed and maintained his personal blog in his spare time. In its early days, his blog focused mainly on writing tips, personal reflections and motivational strategies. In 2010, his blogging activities were even recognised by ICT Watch, a civil society organisation that campaigns for healthy Internet use, which awarded him the 2009 Healthy Internet Blog Award.

Ahead of the 2014 Presidential Election, however, Jonru’s blogging activities took a sharp turn. A staunch supporter of Prabowo Subianto, his Facebook page and other social media accounts were soon dedicated to lambasting and ridiculing Jokowi and anything or anyone related to him and his administration. His posts were immensely popular among his followers, many of whom were also Prabowo supporters, and at the same time, greatly annoyed fans of Jokowi.

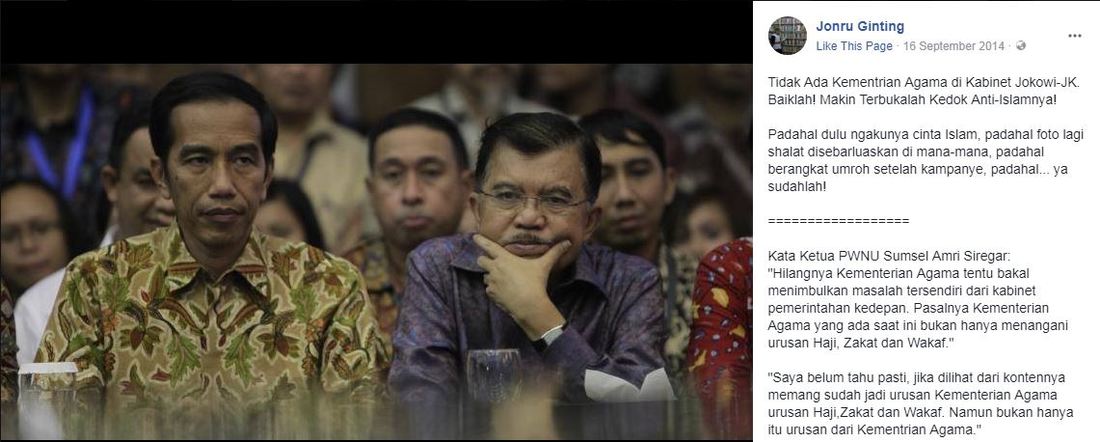

In one post, for example, Jonru wrongly claimed that there would be no Ministry of Religious Affairs under a Jokowi administration.

He has repeatedly suggested that Jokowi’s mother is not his biological mother.

In another post, which he subsequently deleted, he claimed a picture depicting former Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama shaking the hand of King Salman of Saudi Arabia was a hoax. When Presidential Palace photographer Agus Suparto clarified that he had taken the image, Jonru responded with a lengthy post criticising Ahok’s supporters for their reaction to the incident.

Jokowi’s online supporters have mocked Jonru mercilessly, even using his name as a synonym for slander, creating the new verb menjonru, meaning “to justify (or consider halal) slandering people you dislike”. But this was exactly how he was able to build such a high profile so quickly: by being deliberately provocative, goading and stimulating his supporters and enemies into online debates.

Fame and notoriety were not the only things he gained from his political postings. His online reputation paved the way to connections to political elites, or their operatives. In 2014, for example, Jonru posted a photo with Prabowo at his Hambalang residence. Likewise, the legal team defending him against the hate speech accusations is from a legal aid organisation chaired by Fahira Fahmi Idris. She is a member of the Regional Representatives Council (DPD) and daughter of former minister and Golkar politician Fahmi Idris.

Gearing up for 2019

Jonru is just the latest in a string of recent fake news and hate speech arrests. In June, for example, brothers Rizal and Jamran were sentenced to six months in prison for racially charged hate speech against Ahok, and for accusing Jokowi of being a member of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). In late August, police arrested three people said to be involved in the “hate-speech syndicate” Saracen, and last month, cleric Alfian Tanjung was arrested for a second time for accusing Jokowi of being of Chinese descent and having links to the PKI.

While the president’s spokespeople have always insisted that Jokowi has not been bothered by Jonru’s activities on social media, his arrest comes at a time that the government is clearly cracking down on its online critics.

There is no doubt that the past few years have seen an explosion in online hoaxes and misinformation designed to discredit the government. But Jonru’s arrest should also be understood in the light of the growing competition ahead of the 2019 Presidential Election. It is telling that the lawyer who reported Jonru to the police, Muannas Al-Aidid, is a member of the Nasdem Party, one of Jokowi’s main backers in the legislature.

A recent Saiful Mujani Research & Consulting (SMRC) survey found that in a head-to-head race, Jokowi was still far more popular than Prabowo, leading his former rival 57 per cent to 32 per cent. But as the 2014 Presidential Election demonstrated, a gap of this magnitude is not insurmountable.

Jokowi and his campaign team know this well. In December 2013, a SMRC survey recorded Jokowi’s popularity at 62 per cent. By July 2014, it had plummeted to 46 per cent. In the same period, Prabowo’s popularity climbed from 23 per cent to 45 per cent.

Jokowi’s team had overlooked the fact that Prabowo’s campaign team had also seen the potential in social media and recognised it as the new battleground in Indonesian politics. Prabowo’s team recruited social media professionals who made some savvy decisions to mobilise support online. It was not surprising that they joined forces with Jonru with the goal of winning the election for Prabowo.

Jokowi’s team clearly doesn’t want to make the same mistake twice and that is why it is moving now to muzzle those figures who might erode his popularity in the long lead up to the 2019 Presidential Election.

Jonru is part of a new breed of campaign operatives known in Indonesia as political “buzzers”, whose emergence was enabled by social media, accommodated by the electoral system, and nurtured by politicians. Political buzzers are not limited to supporters of Prabowo. There are also plenty of buzzers who tweet support for Jokowi and his administration, while mocking and insulting Prabowo, for example, Denny Siregar, Alifurrahman S Asyari or the anonymous Twitter user @kurawa.

They may start their “careers” as genuine supporters of a certain candidate in an election, or they might simply be out to make money. Regardless of their initial motivations, political buzzers can make a fortune during political campaigns.

This is why there are many established and aspiring political buzzers ready to support Jokowi, Prabowo (or any other candidate willing to pay) ahead of the 2019 Presidential Election. They know very well that their social media activities may land them in prison for spreading hate speech if their candidate ends up losing the election. But for many this is a risk they are willing to take, so long as the money rolls in.

So, while this may well be the last we see of Jonru, it will not be a surprise if by the time the 2019 election comes around other buzzers have taken his place.