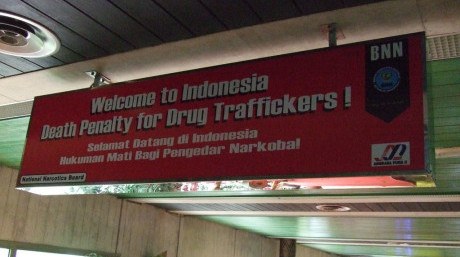

For months, Indonesian President Joko Widodo – popularly known as Jokowi – has repeatedly stated his determination to show no mercy to drug offenders facing execution.

Jokowi is even reported as having rejected the applications for clemency by drugs offenders without reading them. That includes those submitted by Australians Myuran Sukumaran and Andrew Chan.

Last week, the pair filed a last-ditch request with the Administrative Court to reverse this. Allegations of attempts by judges to extract bribes from the two Australians in exchange for lighter sentences have now also been reported to the Judicial Commission.

Regardless of these two new proceedings, Indonesian Attorney-General H.M. Prasetyo has reiterated the government’s determination to execute death row inmates in the coming weeks, including Sukumaran and Chan. There are reports that all 58 drugs offenders now awaiting execution could be dead by the end of the year if Jokowi has his way.

Despite this, Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi announced only last week that Jokowi had ordered new support, including legal assistance, for 229 Indonesians facing execution overseas. Many of these are said to be drug offenders.

This announcement is an extraordinary development. It makes it hard to understand exactly where Indonesia stands on the death penalty.

Is it really the case that Indonesia is determined to execute drug offenders – both foreign and local – if they are caught in Indonesia, but will spend money to help Indonesian drug offenders avoid execution provided they are caught overseas?

This position seems internally contradictory both in regard to the death penalty and drugs policy. It is also discriminatory. It makes it hard to avoid the conclusion that the Jokowi administration’s approach to drugs and death is driven more by populism than principle.

The death penalty under SBY

No doubt the Indonesians on death row overseas attract great sympathy in Indonesia – so much so that in 2011 then-president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s (SBY) government set up a well-funded and very effective taskforce to provide them with legal assistance. There are claims it has saved around 60 Indonesians from execution. In at least one case in Saudi Arabia, it paid “blood money” to have a death sentence commuted to imprisonment.

SBY’s taskforce was a response to popular horror at the fate of Indonesian domestic workers – many of them maids – who had murdered their employers after abuse and, in some cases, rape and then faced hanging or, in Saudi Arabia, decapitation. But not all Indonesians facing death overseas are abused maids. They include drug offenders too.

SBY had a deep dislike for the death penalty and agonised over clemency decisions. This influenced his policy, even if he avoided making his personal position public and was not always consistent in practice.

In any case, during his administration Indonesia remained unenthusiastic about the death penalty. SBY personally put in place an unofficial moratorium on the death penalty from 2008 to 2013 (when he allowed some executions to take place). This approach had its shortcomings, but it generally sat well with the help he offered Indonesians on death row overseas.

Jokowi’s policy lacks even this level of coherence. He has reversed SBY’s hesitation on executions but also confirmed his commitment to helping Indonesians on death row overseas – presumably because walking away from them would be very unpopular in Indonesia.

Jokowi’s struggles at home

Jokowi is a weak president who lacks a clear majority in the legislature. His compromised performance in his first 100 days has shocked many of his supporters. Some fear he has fallen under the sway of powerful elite figures like his own party head, former president Megawati Soekarnoputri, the intimidating former intelligence head, A.M. Hendropriyono, and media mogul Surya Paloh.

Jokowi also seems paralysed in the face of the latest round of an epic struggle between corrupt police, supported by many in his own party, and the Anti-Corruption Commission, which the public see as a threatened bastion of good governance. Senior leaders of both institutions face tit-for-tat charges of corruption. Jokowi’s credibility depends on finding a solution to this high-stakes face-off.

With little elite support, Jokowi needs to maintain his popular appeal. He knows his chief political rival, Prabowo Subianto, won plaudits for spending some of his own (extensive) funds to help Wilfrida Soik, an Indonesian maid, beat capital charges in Malaysia last year. Prabowo even flew there to attend court hearings.

Prabowo also won votes with his aggressively nationalist and tegas (firm) image. Jokowi seems to feel real pressure to match this, even to the extent of executing foreigners in the face of growing international condemnation.

This came first from a range of countries whose nationals face execution in Indonesia. They are now being joined by international figures – most recently UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, who called for Indonesia to scrap the scheduled executions. Some senior Indonesians feel their country’s international reputation is at stake.

However, the basic problem for Jokowi is that he seems stuck with two inconsistent populist policies. He is committed to the executions as a “shock therapy” solution to what he says is a rising drugs “emergency”, while promising to continue saving Indonesian offenders facing death overseas.

Anti-death penalty campaigns gain momentum

There are signs of increasing discomfort about this in Indonesia. Quite apart from the lack of any credible evidence that the death penalty has any impact on crime rates anywhere, the statistics on which Jokowi bases his claims that 50 Indonesians die every day from drugs are highly dubious at best, as Indonesian media have pointed out.

Prominent Indonesians, from former judges of the Constitutional Court (including its influential former Chief Justice, Jimly Asshiddiqie) to prison officials to the National Human Rights Commission chairman, have also argued that it is time to consider ending executions for good. Prominent law reform and human rights NGOs have been calling for this for years, and are starting to step up their campaigning.

The abolitionists have not achieved critical mass. But last week, Human Rights Minister Yasonna H. Laoly did say that the government should reconsider whether to proceed with executions. But the same day as Marsudi’s announcement on aid to Indonesians on death row overseas, Yasonna backed down, suggesting executions might instead simply be delayed because the government is preoccupied by the police corruption scandal.

Yasonna is right. Nobody – Indonesian or foreign – should be executed in the current highly charged political climate in Indonesia. They would be casualties of incoherent policy-making, a struggling new government and Jokowi’s image problems, their clemency applications unread.

Despite the obvious contradictions in his position, Jokowi is unlikely to be willing – or politically able – to abolish the death penalty now. However, he should immediately suspend all executions indefinitely until calmer and more measured consideration can be given to his now-incoherent policy, the arguments against the death penalty and the implications for Indonesia’s international standing.

At the very least, long stays should be given so the individual circumstances of all prisoners on death row can be properly considered in a less-pressured context. This would include their arguments for clemency and, in the case of Sukumaran and Chan, the new allegations of judicial corruption in their cases.

On death row, time means hope. For the Indonesian government to rush ahead with its plans for mass killings would be a travesty of justice.

This piece was first published in The Conversation.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] to be used against locals and foreigners, particularly drug offenders, despite condemnation from local anti-death penalty campaigners and multiple states and the fact that the death penalty violates the right to life enshrined in […]

[…] to be used against locals and foreigners, particularly drug offenders, despite condemnation from local anti-death penalty campaigners and multiple states and the fact that the death penalty violates the right to life enshrined in […]

[…] to be used against locals and foreigners, particularly drug offenders, despite condemnation from local anti-death penalty campaigners and multiple states and the fact that the death penalty violates the right to life enshrined in […]

[…] to be used against locals and foreigners, particularly drug offenders, despite condemnation from local anti-death penalty campaigners and multiple states and the fact that the death penalty violates the right to life enshrined in […]

[…] to be used against locals and foreigners, particularly drug offenders, despite condemnation from local anti-death penalty campaigners and multiple states and the fact that the death penalty violates the right to life enshrined in […]

[…] to be used against locals and foreigners, particularly drug offenders, despite condemnation from local anti-death penalty campaigners and multiple states and the fact that the death penalty violates the right to life enshrined in […]

Comments are closed.