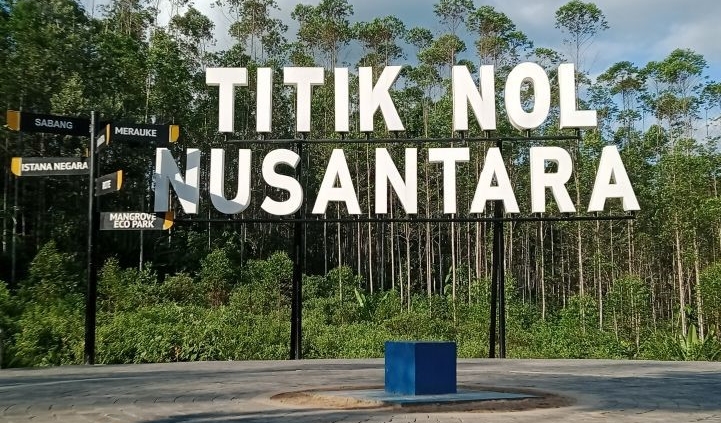

Ground zero, the site of Indonesia’s new planned capital Nusantara. Photo by Antara/Bagus Purwa.

Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo is scheduled to visit Australia next month, his fifth and likely last trip south as Indonesian President. He will be talking trade, querying the AUKUS deal and again urging better visa access for his citizens. The word from Canberra is that Jokowi will also be shopping for lithium for his nation’s Chinese-branded electric vehicle factories in a bid to export cars to Australia.

However, there’s an extra item in his baggage. Jokowi will be driving another agenda, as he does at every opportunity. He wants foreign investors to back a project that he hopes will define his legacy after a decade running the world’s fourth most populous nation. His idea is big, ambitious and risky – shifting Indonesia’s overcrowded, over-polluted and over-stressed capital from Java 1,300 km north to Kalimantan.

Jakarta’s population is 11 million, triple that number if the greater metro area is included. Java has 145 million, Kalimantan just 17.5 million. Indonesia’s population growth rate is 1.1%.

The case for taking the weight off Jakarta – literally, because it is sinking, in parts at 25 cm a year – is watertight. But why not build new in Java, particularly as Jakarta will remain the nation’s commercial and financial centre?

The resolute president explained the selection was not motivated by geography but geometry: ‘We want the relocation to demonstrate the idea of being Indonesia-centric instead of Java-centric. We have drawn a line from west to east, north to south, and found the centre at East Kalimantan province.’

Maybe he should have checked next door in more practical Malaysia, where the administrative and judicial centre is Putrajaya. It is only 32 kilometres south of Kuala Lumpur which remains the nation’s capital. The 1999 shift was pushed by some of the same factors now threatening Jakarta.

Jokowi consulted many about his vision but Queensland University planner Dr Dorina Pojani, author of Trophy Cities, was not among them: ‘The new capitals created since 1900 have been, for the most part, great planning disasters. They are dreary, overpowering, under-serviced, wasteful and unaffordable. In short, they are extremely expensive mistakes.’ Her book claims that in 1900, the world had only around 40 capitals; now there are nearly 200 with five more planned.

Work on the new city of Nusantara – meaning ‘archipelago’ in Javanese and Sanskrit – has so far been funded by the State. But if the US $35 billion-plus project is to rise from a 56,000-hectare site in the jungle by next year, Indonesia will need to proactively court foreign investors.

Through past visits by Australian bankers, Jokowi knows of his southern neighbour’s cashed-up super funds – currently holding $ 3.5 trillion – so he is offering tax holidays, deductions, zero withholding tax and many other incentives. There are reports the project already has ‘commitments’ from investors in the UAE, China, South Korea, and Taiwan and ‘offers’ from European countries.

However, no independent verifiable details of these deals have been released by the Nusantara Capital City Authority, which is closely managing journalist access to the site and plans for the new development. Questions about the project and authority to visit the site have been ignored. At this stage, we do not know whether these are hard deals or daydreams. Probably the latter – if ink had dried on watertight contracts, then Jakarta would be crowing loud to highlight the investment opportunity.

In January 2020, the public was told Japan’s SoftBank Corporation had US $40 billion ready to lend. Staff were sent to examine the opportunity before saying no thanks. Late last year, Bloomberg reported: ‘Not one foreign party – state-backed or private – has entered into a binding contract to fund the project.’

Potential investors may yet see a chance to earn hefty returns from building infrastructure and, of course, a grand palace for the next president, but will the next president maintain Jokowi’s enthusiasm? There are currently three contenders for the top job. The current frontrunner is Governor of Central Java, Ganjar Pranowo, a member of Jokowi’s party, who is said to be in favour of Nusantara. Likewise, controversial former general and current Minister of Defence, Prabowo Subianto and former Jakarta Governor, Anies Baswedan. But the winner’s position may change once the election is over.

Building the new capital is now enshrined in law (Law 3 of 2022). But there is nothing in the legislation about timeframes, or an out clause if foreign capital cannot be raised. These laws will make it much harder for Jokowi’s successor to backflip on the move.

The present schedule has 17,000 government workers moving north in 2024 with 60,000 more relocating a year later. All will require homes, schools, hospitals and all the other necessary facilities and services of a modern metropolis. Also needed will be thousands of entrepreneurs to care for the needs of households.

This will be grossly expensive, and makes it likely that in the event of any future financial crisis, Nusantara would be an early sacrifice. Many would not be upset if that happened. The public servants scheduled to move from their homes, families and friends in Jakarta are not as keen on Nusantara as their boss. Unlike Australians, Indonesians are often reluctant re-locators.

China has been the major investor during Jokowi’s tenure, tipping billions of renminbi into toll roads and nickel smelters. These investments offer more certain dividends than a possible white elephant.

The other concerns for Western investors are corruption – Indonesia ranks 110 out of 180 on Transparency International’s rankings – and the decline of democracy and adherence to the rule of law.

At this stage, the investment outlook for Nusantara looks bleak. In the July chill of Canberra, the normally reserved President may find it hard to pique the interest of Australian fund managers.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/shanghaidaddy/3296581934/in/photolist-aJfZwZ-62iQXy-4MJe21-4MUkf7-SYH2jw

https://www.flickr.com/photos/shanghaidaddy/3296581934/in/photolist-aJfZwZ-62iQXy-4MJe21-4MUkf7-SYH2jw