Rising inequality can reduce the power of economic growth to reduce poverty. Photo by Yulius Satria Wijaya for Antara.

Increasing inequality in Indonesia has raised concern in recent years. Although in general everybody is better off, the gap between rich and poor is widening.

Welfare improvement, as measured by consumption per capita among the richest group, is growing much faster than that of the poorest group, suggesting that the rich are getting richer much faster than the poor. The Joko Widodo government has implemented policies designed to tackle poverty and inequality ranging from health and education protections, to expanding social assistance programs and increasing infrastructure spending.

But what are the odds of Indonesia reducing inequality in the short to medium term? Is greater inequality here to stay? SMERU researchers Ridho Al Izzati, Daniel Suryadarma and I analysed past economic data and estimated future trends to examine the drivers and future of inequality in Indonesia.

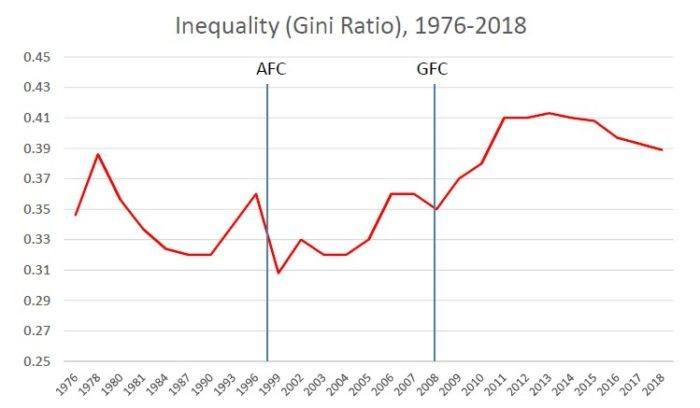

For most of the New Order period, Indonesia experienced high levels of economic growth without increasing inequality. From 1976 to 1990, Indonesia’s economic growth averaged about 7 per cent per year and its Gini ratio actually slightly decreased from 0.35 to about 0.32.

The Gini ratio is a common way of measuring inequality in a society. A Gini ratio of zero represents perfect equality (if everybody earned the same amount) and 1 represents maximal inequality (if all income was earned by one person).

After the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997-1998, however, inequality quickly increased, despite lower economic growth of around 5 per cent per year. In 1999, the Gini ratio was 0.31 and by 2011 it had jumped to 0.41, an increase of a full 10 percentage points in the space of a decade.

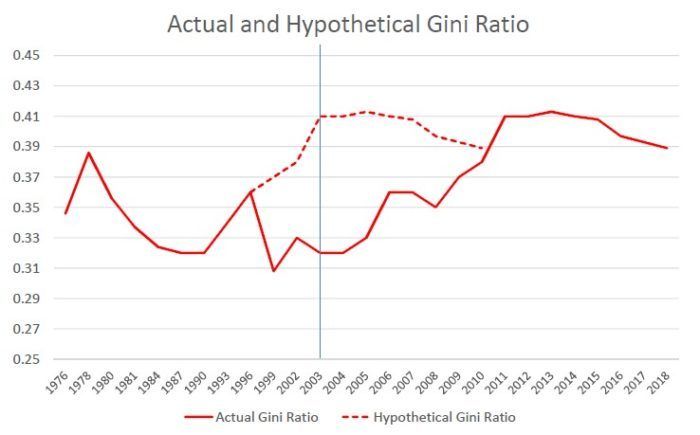

Looking back at Indonesia’s record under the New Order, inequality had, in fact, begun to increase rapidly after 1990, but the Asian Financial Crisis brought it down again, mainly hurting the incomes of the richest Indonesians. Had the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s not occurred, it is likely that Indonesia would have achieved a Gini ratio of 0.41 by 2003.

Scholars describe numerous drivers of inequality, most of which interact with and reinforce one another. Labour-saving technology, which decreases demand for low-skilled workers and requires workers to increase their skills to remain competitive in the labour market, is thought to be an important driver of inequality. Related to this, a high degree of informal work in the labour market can contribute to inequality.

Demographic changes, such as an ageing population, can result in inequality through a reduction in the number of household members of working age. Education also plays a role, as more highly educated people generally have access to better job opportunities and higher wages.

Financial market liberalisation can result in rising inequality, by mainly benefiting the richest portion of the economy. Commodity booms – and the so-called Dutch disease – can also alter the distribution of wealth in a country significantly, contributing to inequality. Geography, usually rural-urban differences, and unequal provision of infrastructure are thought to play a role. Gender is also an important factor. In many countries there are gender disparities in access to education, and a significant gender wage gap. Finally, corruption is thought to contribute to inequality through its diversion of public expenditure.

Unfortunately, analysis to date has tended to be piecemeal, making it difficult to account for the exact contribution of each of the above factors, and the interactions between them, to increasing inequality.

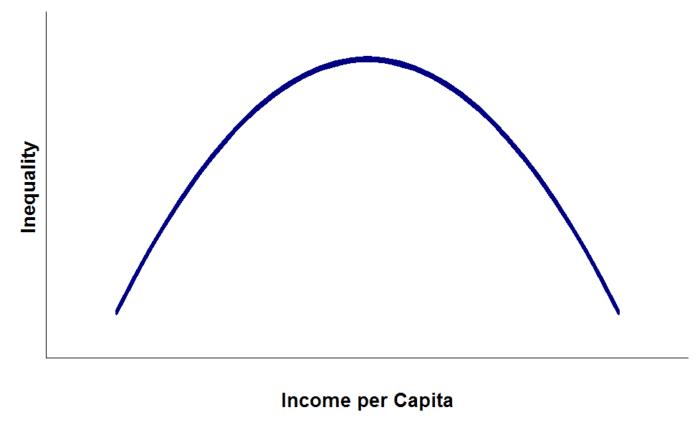

To get a better picture, we used the well known Kuznets’ hypothesis, which predicts that from a starting point of low inequality and low levels of income per capita, inequality will spike as per capita income starts to rise, but will eventually fall again, with continuing further increases in incomes.

Countries move along the Kuznets’ curve due to changes in their structural factors: levels of education, economic sector activity (for example, a shift in economic activity from the agricultural to the industrial sector), rural-urban transformation, and rates of informal to formal work. Examining Indonesia’s record between 1992 and 2011, we find that around 80 per cent of the increase in inequality was caused by changes in these structural factors.

Even though inequality has increased, everybody benefits from economic growth in Indonesia. Increasing economic growth has led to increases in rates of consumption per capita in all segments of the population. So, should Indonesia worry about inequality?

Well, the problem with increasing inequality is that it will eventually reduce economic growth. Concerningly, it also will reduce the power of economic growth to reduce poverty, as the benefits of growth will be felt less by the poor. Furthermore, there is a substantial body of research describing links between inequality and violent conflict. As higher inequality reduces social cohesion, violent conflicts are more prone to occur in societies with high levels of inequality.

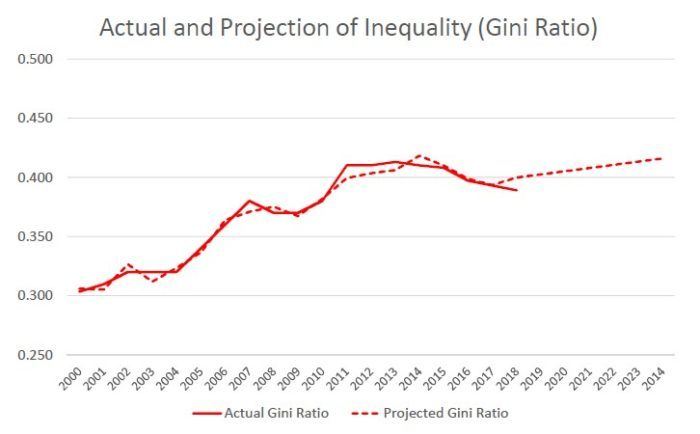

So if one accepts that Indonesia must do something about its growing inequality, what are the best options for addressing it? Given that our modelling suggests that most of Indonesia’s inequality is caused by structural factors, this would seem to be the obvious place to start. Unfortunately, however, our projection suggests that changes in structural factors will not bring down inequality in the medium term.

This suggests that investments in education, shifting economic activities away from agriculture, urbanisation, and changes in the labour market to increase formalisation will take some time to pay off to reduce inequality.

What other options does Indonesia have? Recently, direct cash transfers have found favour among some governments as a way of reducing inequality and poverty. In 2005, for example, the Indonesian government delivered unconditional cash transfers to the poor to reduce the impact of a reduction in fuel subsidies. Another conditional cash transfer was introduced in 2007.

But our modelling suggests that cash transfers can only have a minimal impact on reducing inequality, even if the government expands the coverage to the bottom 40 per cent of the population and the benefit is tripled from the current level.

All of this suggests rather pessimistic prospects for bringing down levels of inequality in the short to medium term. Hence, we may need to prepare ourselves for the reality that a Gini ratio of 0.4 or greater is the new normal for Indonesia.

The views and opinions expressed in this post do not represent the views of the Australian or Indonesian governments. This post was based on Asep Suryahadi’s keynote address at the Indonesia’s Inequalities conference, hosted by University of Melbourne’s Faculty of Arts on 1-2 November.