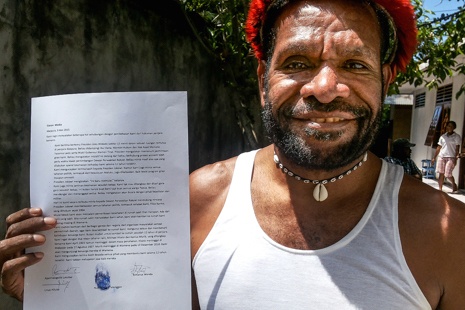

Linus Hiluka, one of the five men granted clemency by President Joko Widodo. Photo by Andreas Harsono.

In an effort to foster peace in West Papua, in May, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo granted clemency to five political prisoners convicted of breaking into a military compound in Wamena, Papua. The president also stated that there would be “a follow-up granting clemency or amnesty to other [political prisoners] in other regions”. With more than 90 political prisoners still incarcerated around Indonesia (primarily Papuan and Moluccan separatists), Jokowi’s plans face significant obstacles.

Article 14 of Indonesia’s 1945 Constitution sets out a number of quasi-judicial powers available to the president. The most familiar of these, clemency (grasi), involves the alteration, reduction or abrogation of criminal punishment, and is sometimes used to convert a death sentence to life imprisonment. Rehabilitation (rehabilitasi) is granted in order to restore the reputation of a person accused of criminal offences who is then acquitted. Amnesty (amnesti) operates in a similar manner to clemency, usually employed to release an entire class of prisoners from incarceration, whereas the final option, abolition (abolisi), resembles amnesty, but is instead granted before conviction, while the case against a prisoner is still pending.

Based on international practice, clemency is usually granted on an individual basis after reviewing a petition submitted by each prisoner, whereas amnesty or abolition are granted to many prisoners at once, without detailed consideration of individual circumstances. Unusually, Indonesia’s constitution vests both the clemency and the amnesty powers in the president – in most other countries this power rests with the legislature. Article 14 does, however, mandate the president to pay regard to the advice of the Supreme Court (Mahkamah Agung) when granting clemency or rehabilitation, and the House of Representatives (DPR) when granting amnesty or abolition.

Although he has steadfastly refused to grant clemency for any prisoners sentenced to death for drug trafficking, Jokowi did extend clemency to three prisoners sentenced to death for murder in March 2015, and, in December 2014, released agricultural rights activist Eva Susanti Bande from prison through the use of clemency. On the other hand, the most prominent cases of amnesty in the post-Suharto era have involved political detainees. President BJ Habibie released about 230 political prisoners (including separatist leaders from East Timor, Papua and Aceh) through 12 separate decrees as a part of Indonesia’s democratisation process during 1998 and 1999, to signal a break from Suharto’s New Order regime. Moreover, in 2005, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono granted amnesty and abolition to 1,424 persons involved in the Free Aceh Movement (GAM). Both of these acts of presidential leniency have been widely feted as successful and appropriate uses of the amnesty and abolition provisions.

In using the same clemency and amnesty powers to release all remaining political prisoners, President Jokowi now faces difficult choices. Clemency, while allowing for a prisoner’s release, implicitly requires the recipient to acknowledge his or her guilt (even though prisoners such as Eva Susanti and Schapelle Corby have attempted to maintain their innocence while simultaneously petitioning the president for clemency). Although there is no explicit requirement to acknowledge guilt in the constitution or the legislation on clemency (Law 22/2002 and Law 5/2010), both laws clearly define clemency as a form of official forgiveness (pengampunan) for a punishment imposed by a court of law. In the explanatory notes to Law 22/2002, clemency is described as “a gift from the president in the form of forgiveness… As such, the granting of clemency is not a technical issue of justice and does not relate to an assessment of the judge’s decision.” Clemency is seen as an executive award to reduce lawfully imposed punishment, rather than an act to overturn a judicial finding of guilt and declare innocence based on new arguments or evidence, such as with case review (peninjauan kembali). Accordingly, each of the five West Papuans at least indirectly acknowledged responsibility for their crimes by accepting release from prison (although there are conflicting reports as to whether they submitted clemency requests to the president, or were pardoned unilaterally).

In 2010, Yudhoyono also granted clemency to two West Papuan political activists jailed for raising the banned Morning Star flag and for taking part in a violent pro-independence rally. Other West Papuan prisoners offered clemency have steadfastly refused to be released. Most notably, in August 2013, a unilateral attempt at granting large-scale clemency to West Papuan political prisoners by Yudhoyono failed, as the prisoners refused to acknowledge guilt for crimes that they say they did not commit. Among those refusing clemency was Filep Karma, perhaps the most well known Papuan political prisoner, who was given a 15-year sentence in 2004 for raising the Morning Star flag. Given such responses, Human Rights Watch has demanded that the Indonesian government: “release all political prisoners with an immediate presidential amnesty rather than demand prisoners admit ‘guilt’ for convictions that violated their basic human rights”.

Based on its historical rationale, granting amnesty for political prisoners in order to signal a break from the past, to facilitate healing and to encourage constructive dialogue with separatist groups would appear a more conciliatory choice for Jokowi than attempting to make further grants of clemency.[1] Granting amnesty (or abolition for prisoners whose cases are still pending in the court system) would not require any implicit admissions of guilt, and would return the prisoners to a position as if they had not been convicted in the first place by “forgetting” rather than “forgiving”. Granting amnesty would, however, require that the president pay heed to the advice of the DPR. Herein lies Jokowi’s dilemma.

Although it is not mandatory to follow such advice (and there certainly have been cases where presidents have ignored the advice of the Supreme Court in granting or rejecting clemency), disregarding the opinion of DPR Commission I is an unlikely move for an inexperienced president with a limited legislative mandate. In justifying Jokowi’s decision to grant clemency rather than amnesty in May, the Minister of Justice and Human Rights Yasonna Laoly stated: “We are concerned about the political process at the House.” As he foreshadowed, in late June, lawmakers refused to support Jokowi’s proposals to grant amnesty to remaining political prisoners due to fears of legitimising the Free Papua Movement (OPM) and the perceived risk that released prisoners would incite disaffection for the Indonesian administration in Papua.

Jokowi therefore has the option to grant amnesty unilaterally, angering his parliamentary backers, or keep selecting individual prisoners for clemency, which pressures them into acknowledging guilt. Neither looks promising to facilitate the peace and societal healing he has promised.

[1] It is an open question whether President Jokowi could grant clemency followed by rehabilitation in order to re-establish the good name of the prisoner, as suggested by Tedjo Edhy Purdijatno, the coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs. The conventional understanding of ‘rehabilitasi’, however, is that it is awarded after an acquittal in order to restore reputation, rather than after a conviction absent punishment.