The issue of Australia-Indonesia relations featured prominently in Sunday’s presidential debate between Jakarta Governor Joko Widodo and former general Prabowo Subianto, the third in a series of televised debates between the rival candidates.

The topic arose explicitly when the Governor, popularly known as Jokowi, asked Prabowo about his views on Indonesia’s “up and down, hot and cold” relationship with Australia. “I think the problem is Australia’s, not ours,” Prabowo responded.

Prabowo used strong language, claiming that Australia has “some sort of suspicion or phobia towards us”. The use of the word “phobia”, in particular, is concerning. It suggests that he sees Australia as irrational in its approach to Indonesia – or even as having a fear or aversion which is disproportionate to any actual threat.

If Prabowo wins on July 9, this perspective doesn’t seem to leave much room for optimism that the relationship can improve – or much emphasis on the role of Indonesia in trying to improve it.

Jokowi’s perspective seems less disquieting. He describes the relationship as colored by a “lack of trust”, as demonstrated by the phone tapping scandal (link is external) and tensions over Australia’s asylum seekers policy. He is concerned that Australia sees Indonesia as a “weak country”.

The Governor refers to Indonesia’s role in addressing this perception, arguing that “we have to show that we are a country with dignity, and not let other countries treat us as weaklings”.

While Sunday’s debate revealed that Jokowi and Prabowo have different explanations for the problems in the relationship, both are worrying. While the relationship has improved recently, as signalled by the Indonesian Ambassador returning to Canberra in May, the candidates’ remarks signal concerns for the future.

Whichever candidate wins the election on 9 July, it’s clear he will begin his presidential term with a pessimistic outlook on Australia’s approach to Indonesia. Australia may have a harder time maintaining or improving diplomatic ties than it has had with outgoing President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY).

The former general’s views are predictably more hard-line than those of his opponent or the outgoing president. His presidential campaign has been characterised by references to economic nationalism, territorial integrity and national interests.

His pledge to bolster Indonesia’s armed forces suggests that Prabowo will put more emphasis on border security than SBY did. Responding to a question in the debate about asylum seekers, he said: “We will not surrender one centimetre of territory”.

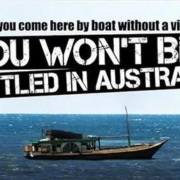

Prabowo’s views on border security might clash with Tony Abbott’s unbudging position on Australia’s own borders. Should Prabowo come to power, it is possible that Australia will encounter problems in its negotiations over asylum seekers.

The Australian Navy’s breaches of Indonesian waters in December and January (link is external) are sure to have colored Prabowo’s views on Australia’s respect for Indonesia’s sovereignty.

Even if Jokowi wins the election, the Australian Government should be concerned about his perceptions of a “lack of trust”. Of course “trust” is a difficult concept in interstate relations. Realists do not expect states ever to trust each other. They believe that national interests should come first. They never rely on the promises of other states.

But in reality, a certain degree of trust develops over time in particular diplomatic relationships. We would not expect one state to trust another unconditionally and trust may be misplaced at times. But ongoing, complex bilateral relationships inevitably involve some reliance on each other to act in particular ways – for example, to honor trade agreements or to respect each other’s borders.

Australian diplomacy towards Indonesia does rely on a certain degree of trust in order for the economic and security relationship to be maintained, and (ideally) to grow.

Given Indonesia’s rapid economic growth and its importance as a strategic partner in Asia Pacific affairs, addressing the trust deficit is crucial. Whether this deficit is perceived or “real” is immaterial; perceptions color decision-making, and a lack of trust can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies.

There are always fluctuations in Australia-Indonesia relations, and of course it is up to both governments to work on the relationship. But the Australian Government should be aware that – particularly if Prabowo wins the election – it may be dealing with an Indonesia that is less interested in trying to be “good neighbors”.

It should at least try to overcome the perception that Australia is irrational or even phobic; otherwise will find itself with little room to maneuver.

This article was first published on The Conversation (link is external).