Surveys suggest about 80 per cent of Indonesians get their information from television. Photo by Andika Wahyu for Antara.

On 20 March, a day after the vice presidential debate featuring Ma’ruf Amin and Sandiaga Uno, President Joko Widodo and Ma’ruf’s campaign team reported online publication tirto.id to the Press Council for sharing a “hoax” meme.

Tirto tweeted a comic of Ma’ruf saying “adultery can be legalised”. The fictional character of “Pak Tirto” responded to Ma’ruf by saying “Okay guys, so in the future don’t forget to provide 3-finger brand condoms” (Oke gaes, jangan lupa ke depannya sedia kondom cap 3 jari yes).

The Jokowi-Ma’ruf team were furious because the comic quoted only a part of Ma’ruf’s original statement, which was: “We invite [all Indonesians] to oppose and fight slanderous claims, like if Jokowi is elected the Ministry of Religious Affairs will be disbanded, the call to prayer will be banned, adultery will be legalised. I swear to God, for as long as I live, I will oppose these efforts to slander us.”

At first, Tirto claimed that by sharing the comic it was simply providing an example of the type of hoax that Jokowi and Ma’ruf were complaining about. But after receiving a highly critical response, it deleted the tweet and apologised to both the public and the Jokow-Ma’ruf campaign team.

But the campaign team was unsatisfied and social media users continued to attack Tirto. Many were disappointed because Tirto had built a reputation for producing high quality, impartial journalism. Respected independent media monitor Remotivi even questioned whether Tirto should be forgiven.

Questions about the independence of the Indonesian media always intensify approaching elections. In fact, there is a long history of partisan media in Indonesia. Before the New Order came to power in the mid-1960s, for example, political parties, such as the Indonesian Socialist Party (PSI), the Indonesian National Party (PNI), the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), Nahdlatul Ulama (which was then still a political party), and Masyumi all produced their own newspapers. Although they were partisan, they were written, printed and distributed by the organisations themselves – people who bought the papers knew what they were getting.

Television, meanwhile, was first broadcast in Indonesia in the early 1960s. For the first 25 years of the New Order period, there was only one television station in Indonesia: the state owned TVRI. Soeharto’s political vehicle Golkar Party used the station as a vehicle for propaganda. It wasn’t until the late 1980s and early 1990s that the television sector was finally opened up to private operators, many of which happened to be helmed by Soeharto’s children and cronies.

Television has played an increasingly important role in the media industry since the fall of Soeharto. Surveys suggest about 80 per cent of Indonesians continue to get their information from television. After the fall of the New Order, there were attempts to create a freer broadcast sector. The Soeharto-era Department of Information was dissolved, a new Broadcasting Law was passed in 2002, and the independent Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) was established. But the KPI has not been able to defend the public interest to the extent that reformers hoped, and the broadcast industry remains in need of ongoing reform.

One of the defining features of the post-Soeharto period has been the concentration of Indonesian media in the hands of less than a dozen powerful figures. Television operators have traded shares allowing certain individuals to control more than a single station, in violation of existing media regulations.

At the same time, new political parties have emerged, including some led by broadcast media moguls. Of the 10 national free-to-air television stations in Indonesia, more than half are now owned by figures with political interests.

Some might argue that this connection between media and political parties is no different to the time when political parties published their own magazines. But there is a difference. These television companies have obtained licences (often through opaque processes or because of their proximity to the Soeharto family) to broadcast on public frequencies.

Media partisanship was evident during the time of the first direct presidential elections in 2004, when Aburizal Bakri and Surya Paloh both took advantage of their television stations (ANTV and Metro TV, respectively) to promote their attempts to become Golkar Party’s presidential candidate.

But in 2014, partisanship really took off. While Bakrie and Paloh were affiliated with the same party in 2004, within 10 years, Paloh had established his own political vehicle, Nasdem, and began using Metro TV and Media Indonesia to promote its interests.

Meanwhile, Hary Tanoesoedibjo, owner of the massive Media Nusantara Citra (MNC) Group, which controls four television stations (RCTI, GTV, MNC TV and iNews), a radio station, Koran Sindo newspaper and online publication Okezone, dipped his toes in the political waters as a vice presidential candidate for Hanura. This resulted in a few memorably ham-fisted attempts to promote the Hanura presidential candidate pair of Wiranto and Hary Tanoe on RCTI, such as in the shambolic “National Quiz” (in which a caller recited an answer before the host had asked the question) or the candidates appearing as cameo guests on popular soap opera Tukang Bubur Naik Haji (Porridge Seller Goes on the Hajj).

The problems with this polarised and highly partisan media environment came to a head on the night of the presidential election in 2014. Surya Paloh’s Metro TV backed Joko Widodo and Jusuf Kalla, while Bakrie’s tvOne supported Prabowo Subianto and Hatta Rajasa. Metro TV and tvOne each published their own “quick counts” in support of their preferred candidate, resulting in the absurd situation of Joko Widodo declaring victory on Metro TV and Prabowo-Hatta declaring victory on tvOne.

Despite the many violations and problems that occurred during the 2014 campaign, little has changed. Stations that the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) named as “enemies of press freedom” (Metro TV, tvOne, RCTI, MNC TV, Global TV) were even granted 10-year extensions to their broadcasting licences by the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) and Ministry of Communications and Information in 2016.

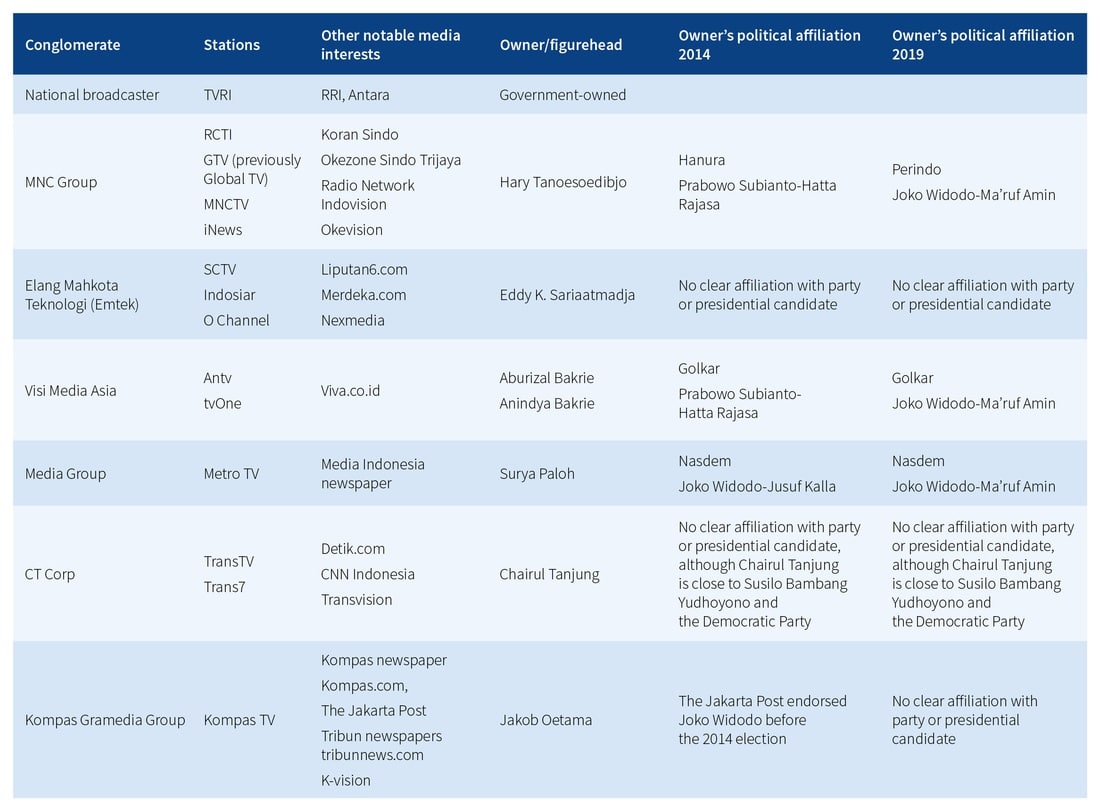

So, how partisan is the media approaching the 2019 elections? Not much better than five years ago. Let’s take a look at the spread of major television channels and their owners’ political affiliations.

Major television stations and their owners

One of the most significant political changes to occur in 2019 has been Golkar’s decision to back Joko Widodo. As a result, reporting on tvOne has not had the same pro-Prabowo tone as in 2014. Further, in 2019, Hary Tanoe has also switched political allegiances. There have been allegations that he did so under duress. In 2017, Hary Tanoe was named a suspect for intimidating an Attorney General’s Office (AGO) official who was investigating allegations of corruption related to a tax refund that the Hary Tanoe-linked company Mobile-8 Telecom received in 2009. Not long after investigations began, Hary Tanoe declared that Perindo would back Joko Widodo in the 2019 elections. Sceptical observers have noted that there have been no developments in the intimidation case since.

While there was vigorous competition between rival media companies in 2014, by 2019, all the major media moguls have now fallen in behind Joko Widodo and Ma’ruf Amin. As a result, there has been far less contestation of ideas and policies in the mainstream media. The democratic era has failed to provide the healthy and diverse broadcast media environment that reformers had hoped for. The major players of the Soeharto era remain, and they have simply adapted their content to suit their owners’ economic and political agenda, without considering the public, or the responsibilities that come with using public frequencies.

With television coverage mostly supportive of the government, there has been a much more vibrant and interesting debate online and on social media. The public have had to seek diversity of content online, rather than through broadcast media. This helps to explain why Tirto’s “hoax” meme slipup provoked such a strong reaction. The public were dismayed that one of the few seemingly impartial outlets now also appeared to be taking sides, and was engaging in the spread of unverified information, hoaxes and fake news so often seen online in Indonesia.

As consumers concerned about media diversity, we should criticise Tirto, just as we should criticise other online media outlets that share hoaxes and misinformation. Tirto has apologised to the public and the Jokowi-Ma’ruf campaign team. But the consequences it has received from its error in judgement seem disproportionate to the (lack of) consequences faced by television stations, which operate on public frequencies, but are driven by political interests.

There is no doubt that Tirto made a major blunder in posting the meme. But it was not Tirto that broadcast a falsified citizen journalism “report” claiming that Prabowo would win a couple of weeks ahead of the 2014 election. It was not Tirto that broadcast Prabowo’s “victory” on the basis of dodgy quick counts. It was not Tirto that broadcast live Wiranto and Hary Tanoe’s declaration as presidential candidates using a public frequency, or broadcast a fake “quiz” to promote its owner’s presidential run.

If this continues, Indonesia’s unfinished business of media reforms will continue to be a major problem for free and fair politics in the country.