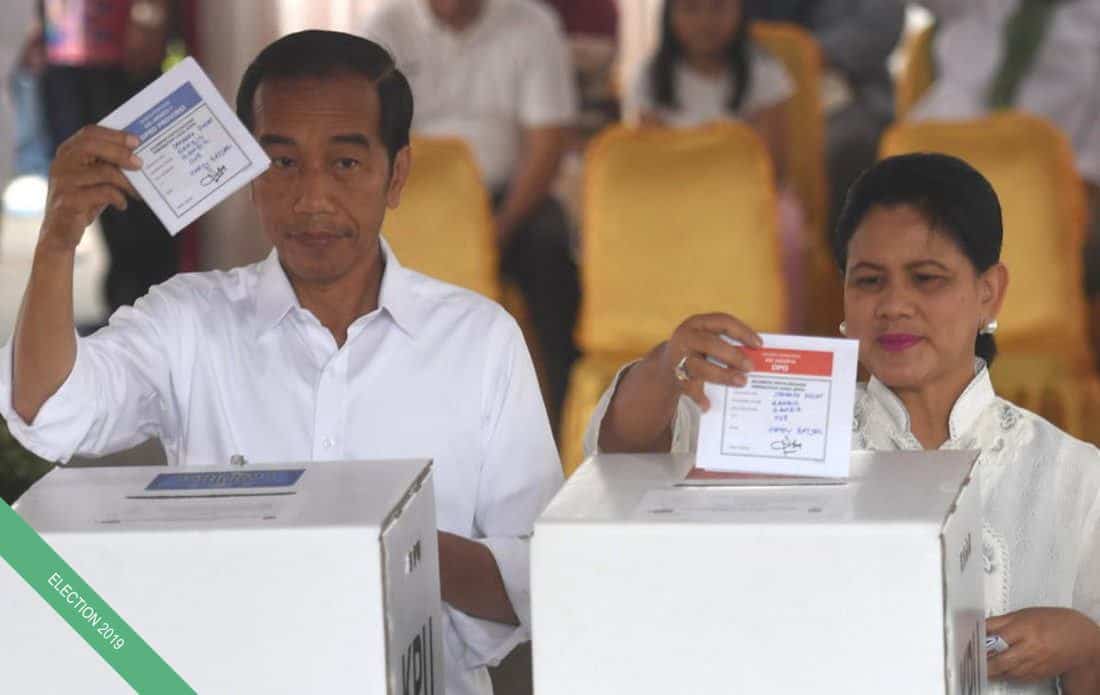

President Joko Widodo and First Lady Iriana voting on 17 April. Photo by Akbar Nugroho Gumay for Antara.

The presidential election is over, and most quick counts suggest President Joko Widodo will be re-elected by a margin of 7 to 9 per cent, securing about 54-56 per cent of the vote compared to Prabowo Subianto’s 44-46 per cent.

Despite many pre-election surveys predicting Jokowi would increase his margin over Prabowo, the winning margin is little changed from the 2014 results. Jokowi appears to have only added about 1-2 percentage points, suggesting he has largely failed to gain broader support, despite his incumbency.

In fact, preliminary analysis of results show increasing polarisation among the population. Jokowi gained support in non-Muslim majority areas, such as Bali, East Nusa Tenggara, and North Sulawesi, and the ethnically Javanese dominated provinces of Central Java, Yogyakarta and East Java. Prabowo, meanwhile, gained support in majority-Muslim areas, and won the majority of votes in several provinces that Jokowi won in 2014, such as South Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, Bengkulu and Jambi.

This trend might demonstrate the return of historical ideological divisions between Islamists and pluralists resulting from the increasing use of religious identity politics in electoral contests. These divisions could get even worse over the next five years if the constellation of power remains the same. This is especially likely if opposing camps fail to negotiate power and resources approaching the 2024 presidential election.

In the months approaching this election there was an increase in voters declaring an intention to golput for political reasons. Many predicted that the Sexy Killers documentary, which demonstrated connections between the mining industry and powerholders from both presidential teams, and was viewed more than 10 million times on YouTube in the days approaching the election, might also affect levels of golput.

But golput levels appear much lower than many predicted. Quick counts suggest a turnout of about 80 per cent, and only 2 per cent invalid or spoiled ballots, suggesting that only a small number of golput non-voters turned up at voting booths to destroy or spoil their votes. The slight change in election results suggests that actual numbers of golput ended up being quite small, and any increase in voter turnout was distributed equally between both camps.

More importantly, the narrower than expected margin between Jokowi and Prabowo may leave open the possibility for Prabowo to dispute the results at the Constitutional Court. Over the past few days, Prabowo has declared victory (on multiple occasions), and has referred to internal counts to back his claims, not unlike he did in 2014. He and his supporters have attempted to undermine the legitimacy of quick counts and have cast doubt on the integrity of the General Elections Commission (KPU).

But despite his claims of widespread cheating, I don’t believe his supporters are angry enough to riot, or engage in mass demonstrations of “people power” as Prabowo backer and former People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) chair Amien Rais threatened.

Besides, given the shallow ideological cleavages among political parties, it is likely that there will be horse-trading between the opposing camps behind the scenes (if it is not occurring already), which will reduce tension. This does not necessarily mean that the opposition will end up in the same political boat with the government. Negotiations could relate to economic activities, gaining business concessions or access to resources. The objection to the quick count results might simply be a means for the opposition to improve its bargaining position to negotiate with the winners. Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan’s attempt to meet Prabowo a couple of days ago is a signal that the Jokowi camp is preparing to negotiate.

The next few months will be particularly interesting as the results of the legislative election become clearer. Jokowi has a broader political coalition than in 2014, meaning that it should be easier for him to consolidate his power. His party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), came out in front, and appears to have won more than 20 per cent of the vote, putting the party (and Megawati Soekarnoputri, in particular) in a better position to negotiate with other parties in their alliance.

A crucial difference from 2014 is that in 2019, civil society groups and volunteers did not mobilise to the same extent to propel Jokowi to victory. Jokowi had already attracted significant political party support, and many pro-democracy activists had been turned off by his broken promises around human rights, and selection of Ma’ruf Amin as running mate. This means political horse-trading is likely to play an even bigger role in the selection of his new cabinet than in 2014. Civil society activists will likely see their role in Jokowi’s second administration reduced further.

Given that it is Jokowi’s last term and he has a broader base of political support, is he more likely to pursue a reform agenda? It seems unlikely. While he has more political party backing, he will still be supported by a broad and unwieldy coalition whose members will mainly have their own interests at heart. His political party supporters will be more concerned about preparing potential candidates and resources for the 2024 presidential election than with pursuing major reforms, and this will determine the constellation of power in Jokowi’s coalition.

For this reason, I suspect the Democratic Party will join the ruling coalition. Since the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, it has been clear that Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono is preparing his son, Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, for a presidential run. If the Democratic Party continues to back Prabowo over Jokowi, it will struggle to increase Agus’s popularity and accumulate economic resources for the 2024 presidential campaign. We are likely to see it switch allegiances soon.

Gerindra and the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), meanwhile, both appeared to have performed very well and will likely remain in opposition. Although this will provide them with limited opportunities to acquire financial resources, their strong performance from opposition over the past five years will give them confidence to maintain this stance. Besides, they know that they already have the strongest potential future presidential candidates on their side, such as Anies Baswedan and Sandiaga Uno. Over the next five years, I suspect Gerindra and PKS will continue to play to their base, and rely on the support of the conservative Islamic community. Jokowi will continue to counter the opposition by using the same pluralist narrative.

Against this backdrop, political actors will continue to cling to their opposing pluralist and Islamist ideologies. Consequently, Indonesian society could continue on its current path and become even more polarised, especially approaching the 2024 presidential election. Regardless of the Jokowi administration’s intentions, fundamental issues such as past human rights violations, inequality and agrarian conflict will continue to remain marginal over the next five years.