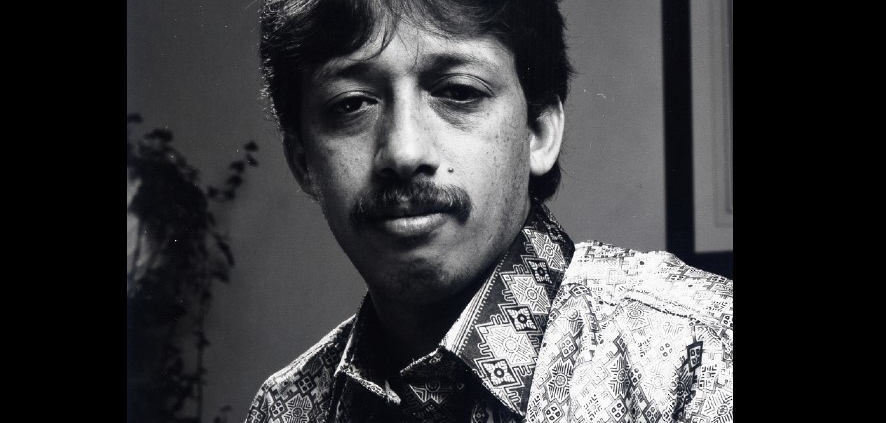

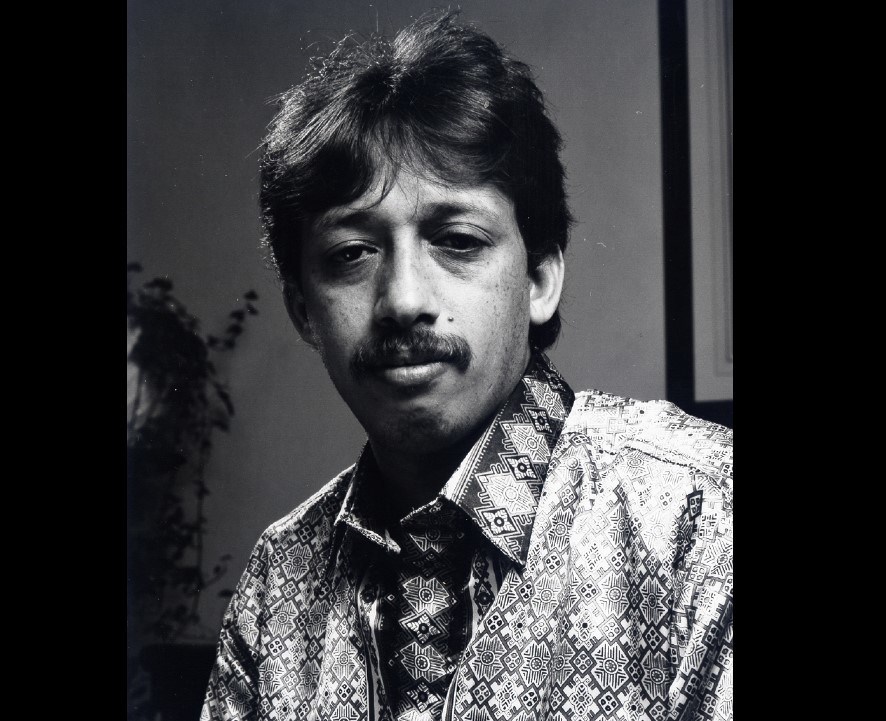

Munir Said Thalib.

“Islam is a religion of civilisation. Extremism and intolerance destroy civilisation. This is in contrast with the function of religion, which is to improve human life.”

At a glance, you might think that these are the words of a philosopher or religious figure. But they are not. They are the words of Munir Said Thalib, Indonesia’s most famous human rights defender, who was poisoned to death 16 years ago today.

Munir died on Garuda Indonesia flight GA974 from Jakarta to Amsterdam on 7 September 2004. An autopsy carried out by the Dutch authorities showed that his body contained arsenic at levels three times the lethal dose. But the Indonesian government has never followed up on the report of a fact-finding team (TPF) to order an independent investigation into his case.

Who was Munir, and how relevant is his activism and thinking to the state of human rights in Indonesia today?

The quote above demonstrates Munir’s inclusiveness. His experiences of violence and religious extremism led him instead to inclusiveness, and a love of life through the diversity of human faiths.

Despite the quote above, the Munir we knew was not someone who helped others out of religiosity. He rarely uttered religious remarks. His apparent hiding of his religiosity may have been the result of his interactions with the weak and the oppressed. He once told me, “If a worker has an accident at the workplace or on the street, we should all be ready to help him or her, without thinking about whether our actions are in line with the Qur’an or the Bible.”

In his youth, you would not find Munir making such remarks. His early years were marked by violence. He often told stories about how when he lost his temper, he would hit people or throw things at them. As a human rights activist, he once received an award and was accused of misusing the cash prize. Media reports of the incident reached his neighbourhood and Munir was very angry. “If that happened long ago, I would have tossed a glass at the person,” he said. “People can accuse me of anything, but not for being a thief… That saddens me the most.”

He once told liberal Islamic scholar Ulil Abshar-Abdalla that there was a period in the 1980s when he followed extremist Islam, and his bag “always contained knives”. This was at a time when President Soeharto cracked down Islamist activism in the name of Pancasila. Munir considered himself as a defender of Islam, ready to fight against the enemies of Islam.

The young Munir’s inclination to anger affected everything, from his relationships to his approach to religion. But later, while studying at Brawijaya University in Malang, he became more reflective. Brawijaya Professor Malik Fajar, who died today, was highly critical of Munir’s approach to religion. He asked Munir, who was also an activist with the Indonesian Association of Islamic Students (HMI), to read the organisation’s values, which were written by prominent progressive Muslim intellectual Nurcholish Madjid.

Munir realised that Islam recognises injustice and that it is there for those who have been violated. Munir changed overnight. He became very spiritual in his religious practice, transcending formal lines of religion. He prioritised improving himself and the lives of others.

In this sense, Munir was sometimes at odds with those whose understanding of Islam was limited to the text, without a greater reflection on the context of the teachings. Over and over, Munir encountered people who saw human rights as a western product. Islam does not recognise human rights, they said. And over and over, he would explain that human rights are a result of the development of civilisation. Human rights were born out of the suffering of victims all over the world: war victims, victims of genocides, forced disappearances and other forms of violence that continue today.

Munir’s spirit to carry the torch of justice is in line with the general spirit of the Qur’an: to realise and uphold justice, equality and peace in society. Siding with victims, workers and the poor was at the core of Munir’s practice of justice. He believed upholding humane values like justice should be part of religious culture. Interpretations that differ from the principles of justice should be reviewed.

His struggle was therefore universal. In South Africa, there was Nelson Mandela. In the United States, such universality is remembered in the figure of Martin Luther King. In Indonesia, there was also Kartini, whose letters show a strong engagement with the notion of the universality of human rights, going beyond citizens’ rights. The principle of justice fought for by these humanists is universal in nature and goes beyond abstract understandings of justice.

Munir’s friends knew him as both a human rights activist and an intellectual. He thought deeply on nationhood. In “Nation Building and Rejecting Militarism” (Membangun Bangsa dan Menolak Militerisme) he stressed that to build a strong nation, one could not rely on values that rejected principles of justice. This is why, he said, militarism was so dangerous in attempts to rebuild a nation with democracy as its founding basis.

For Munir, nationhood went beyond narrow “nationalism” or “chauvinistic nationalism”, which prioritises national identity or national honour over human rights. When he accepted the Right Livelihood Award, Munir expressed cosmopolitan thoughts on being a global citizen in “an integrating world.” In the future, he said, “[W]e all need to consider the possibilities of a united world based on the sense of humanity and solidarity. Crimes committed by a nation-state or in the name of progress and development will be reduced only if we are able to recognise ourselves as part of other humans’ destiny.”

But Munir’s critical thoughts on nationhood and religion led to a backlash. He was threatened and accused of being anti-Islam, communist, and atheist. He was also accused of being an anti-nationalist when he played a significant role in uncovering evidence of human rights violations perpetrated by members of the security forces in Aceh, Papua and Timor Leste.

Munir’s life experience proved that it was no simple matter to revive humanism in Indonesian conceptions of nationhood and religious life. The attacks and accusations targeted at Munir were not just verbal. He also faced physical attacks and, finally, death. A military general publicly stated that he wanted him dead, a package of explosives was delivered to his mother’s door, a bomb exploded outside his house, scores of thugs attacked his office, and, in the end, he was poisoned with arsenic. These are the brutal methods of panicked cowards.

The attacks did not target Munir alone. They were also attacking the universality of human rights. They were designed to spread a sense of fear, to silence people. As a human, Munir experienced fear. But his humanity and solidarity with others helped him conquer his fear.

“What we fear is that fear itself,” Munir would say. Munir may not have intended to quote Franklin D. Roosevelt, or the French essayist Michel de Montaigne, who made similar comments. It was a maxim he used to keep up the struggle and break the tyranny of silence.

He realised that all the things put in the way of activists, from bullets to tanks, were not really major obstacles. The biggest constraint was in the mind. Fear, Munir said, reduces the sensibility and rationality needed to take action. It is no coincidence that similar sentiments are shared by Christianity – “the root of sin is fear.” A faith in humanity and universal justice is a crucial part of inclusive understandings of religion.

One of Munir’s fingers was almost severed when he was defending labourers who had been dismissed. He would comfort those whose family members were victims of forced disappearance. He even helped in the release of a member of the military elite force who was taken hostage by armed groups.

Munir was courageous. He conquered his fear with love. Munir’s widow, Suciwati, remembers him as a man who loved life. He loved his family, looked after his fish, and would not shy from household chores. For Munir, love and solidarity were reflected in his sensitivity to the pain of others. Sensitivity makes it difficult to dismiss the ‘other’.

Munir was loved by the victims he stood for. He went beyond words and ideas and helped bring about meaningful change. As the American philosopher Richard Rorty wrote, “It is not the belief in philosophy or religion, but sensitivity towards others that enable us to be in solidarity with others”.