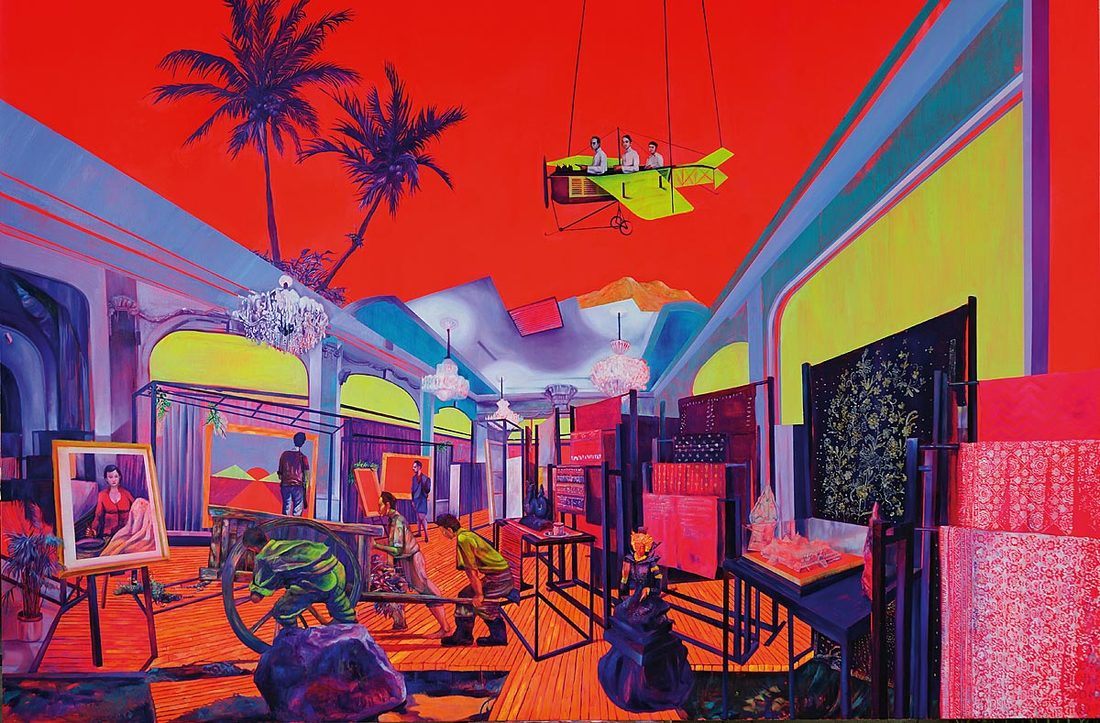

Ladies and gentlemen! Kami present, Ibu Pertiwi! Zico Albaiquni, 2018. Image courtesy of NGA.

If you say “Indonesian art” to switched-on global curators, you get a smile of not only approval but often delight. The Indonesian art that comes to their minds is the energised, politicised (and post-politicised), often-humorous large-scale videos (shown on full walls), paintings (big and bright), photography (usually big and bright), or installations that take any space you like, as long as they take a lot of space.

Heri Dono has been an international superstar for decades, and deservedly so. He has turned to his own Central Javanese culture of performance, whimsy, and sheer cleverness to create works that have more than held their own in any venue and among any audience, anywhere. Dadang Christanto has held Indonesia’s political masters to account like few others, anywhere, expressing grief at personal and wider loss with a power that is universally recognised. Politically driven collectives like Taring Padi and Ruangrupa have expressed their protests with street art of all sorts with a potency that few others, anywhere, have achieved.

Certainly, the protest movement against Soeharto’s New Order regime in the late 1990s was very important. That lit powder kegs smoldering beneath the surface of many creative practitioners. Indeed, many would say this period, as with art works made in the 1980s against President Marcos in the Philippines, created work of power and alchemy that has not been matched. Another instance of the symbiotic relations of politics and art are the street works made by artist collectives in Australia in the 1970s protesting about the then paternalistic, establishment social status quo.

More than 20 years have passed since Soeharto left power, and many aspects of “Indonesian art” have changed, not least the rise of a phenomenal international market for Indonesian works. But the central mainstream works immediately envisaged by those global curators remain very similar.

Those chosen by international curators for the current exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia, on until 27 October, are a case in point. How different are they from those made 20 years ago, if at all? Even the fact that this question can be asked in a fast-moving global art world is telling. Not all works in the exhibition run to the politically, socially relevant tropes of the 1990s but most do.

They are great, there is no question of that. But they raise the question of how long this can go on, and if change is to come, where does this energy go next?

Again, the Philippines gives an instructive comparison: Marcos left power over ten years before Soeharto, so the heat of that Filipino battle has had the extra time to cool. Since then Filipino art has diversified along many new tracks, which is natural, with many fine works made focused beyond or beside socio-political subjects, but the central energy of the struggle years has muted.

So, for Indonesia, where does this current energy go? This is, in fact, of course, not a new question. The long-discussed (indeed over-discussed and over-simplified) debate between artists associated with the Western-focused Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) and the locally focused Indonesian Institute of the Arts (ISI) in Yogyakarta is part of this tension. The selection of Indonesian artists for the 2019 Venice Biennale is another example of this desire to break out from a too-easy “ethnic” trope.

In fact, this question is familiar to members of any culture outside the perceived (still) mainstream of Euro-America. How much to show overt “difference” and how much to conform to an expected type of art, so that mainstream (and picky, often arrogant and supercilious) audiences will recognise some aspect they can access, which might then encourage them to explore further.

This is a tricky process that Australia has grappled with for decades. It is a process in which the experiences of Australian Indigenous artists are especially useful, often selected by international curators for big exhibitions, often “at the expense” of non-Indigenous artists. To be sure, Australian Indigenous art usually looks great – and it looks “different”. And the works seem very “accessible”, usually able to be “appreciated” by international audiences without there being any real knowledge about what makes them what they are.

It is complex. Around the question of what “Indonesian art” is, I wonder about the arts of textile and puppetry, of calligraphy and other Islamically inspired practice, of imagery made in places like Sulawesi, or Flores. What is their future in all this? What is the role of these works made with serious intent, but outside the mainstream favoured by global curators? Will those switched-on global curators be open about this work too? Or won’t they matter?