Prevalence of malnutrition is highest among children in eastern Indonesia. Photo by M. Agung Rajasa/Antara.

Throughout his campaign for re-election, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo emphasised improvements in children’s health and education as a way to boost human development.

Looking towards the “demographic bonus” due in 2020-2030, when Indonesia’s young population comes of age, improvements in children’s health and education could boost economic development as well.

But Indonesia’s most valuable resource – its children – still face impediments to their health and well-being that will likely impact their future, and the future of Indonesia.

Stunting caused by malnutrition has become a high-profile health issue in Indonesia because of its impact on all aspects of development, from human resources to economic growth.

Children are defined as stunted if their height-for-age is more than two standard deviations below the World Health Organisation (WHO) Child Growth Standards median. Its causes include inadequate daily food or nutritional intake, as well as factors such as lack of access to clean water and sanitation, which can result in repeated infections. Beginning in early childhood, stunting has lifelong implications for physical and cognitive development, and so requires comprehensive strategies to tackle both causes and effects.

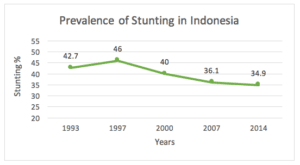

Several government programs have been devised to overcome the problem. Some progress was seen in Jokowi’s first term as president. The prevalence of stunting decreased from 37.2 per cent in 2013 to 30.8 per cent in 2018, according to research by the Ministry of Health. Similar results were found by the Indonesia Family Life Survey, which looked at stunting prevalence over the past two decades, but the rate of decline is still slow.

Prevalence of stunting in Indonesia from 1993 – 2014. Source: Indonesia Family Life Survey.

Stunting leads to significant problems for child health and affects the country’s prosperity, meaning that it is everyone’s business, no matter which side of politics they are from.

In the campaign period, both Jokowi and his rival, Prabowo Subianto, pledged to reduce stunting. The basics were mentioned, such as increasing quality of nutrition in early life, improving the quality of childcare, and improving practices related to water and sanitation, but neither gave specific or practical details of what they planned to do.

Prabowo and running mate Sandiaga Uno promised to address stunting through a national movement called Sedekah Putih, or “White Gift”, whereby nutritious foods like milk and mung beans would be distributed to children in early education. Meanwhile, Jokowi and his running mate, Ma’ruf Amin, pledged to promote breastfeeding up to age two, as recommended by the WHO.

But neither candidate pair gave consideration to issues of equity and equality in tackling stunting. A lack of coordination between central and local governments, as well as a lack of capacity among some local governments, means that the effectiveness of government programs , despite hopes about decentralisation bringing the government closer to the people and making programs easier to control and evaluate.

Recent reports confirm that there is a higher prevalence of malnutrition among children in eastern Indonesia than in other parts of the country. These figures are also likely to be underestimated because of underreporting. Additionally, the 2017 Sentinel study, conducted by SurveyMETER and MCA-Indonesia, found that the prevalence of stunting in Indonesia among children aged 12 months and under was almost three times higher than the prevalence of wasting and twice as high as the proportion of underweight children.

Next steps

With Prabowo’s party, Gerindra, looking set to become the second largest party in the legislature, will we see a concerted effort from former rivals to move ahead on common goals?

What they could do is clear enough. Indonesia needs a simple but integrated data system linking local and central governments to accelerate the planning of interventions, to close the gap between regions, and maximise multi-sectoral coordination, as well as for monitoring and evaluation. An integrated data system starting from the grassroots could help map malnutrition in the regions and ensure stunting interventions are effective, efficient and well targeted.

Data from the ground level could show which cases require intervention, and assist execution of plans to the right targets. It could also be used to track grassroots progress against national targets,

This approach was trialled in Patianrowo subdistrict in Nganjuk, East Java. Conducted by SurveyMETER in partnership with the Knowledge Sector Initiative and the Nganjuk District Health Office, the trial study aimed to create a data system that could be accessed and used by the local government to tackle stunting.

Local health workers were empowered and trained to collect health data from pregnant mothers and children from birth up to two years of age. This data was then analysed to produce information useful for decision makers, from the provincial policy level down to village heads and community leaders. The study found positive responses from local government stakeholders and will be replicated in 19 other subdistricts in Nganjuk.

Jokowi now has the opportunity to prove his capability as a national leader by influencing local communities to get involved, collaborate, and support efforts against stunting, building a collective sense of ownership and responsibility for the issue. Communities, civil servants and other stakeholders need to be inspired to lend a hand.

The development of human resources is just as important as economic development, or building national infrastructure. The re-elected president should consider empowering local communities by developing an integrated system that can improve human capital, with follow-on impacts for productivity, competitiveness, economic growth, and a better quality of life.

This is not just about avoiding malnutrition for children, but also ensuring a fairer distribution of health workers and facilities that can offer equal opportunities to all Indonesians, so that they can compete globally, increase economic growth, and fulfil their potential.