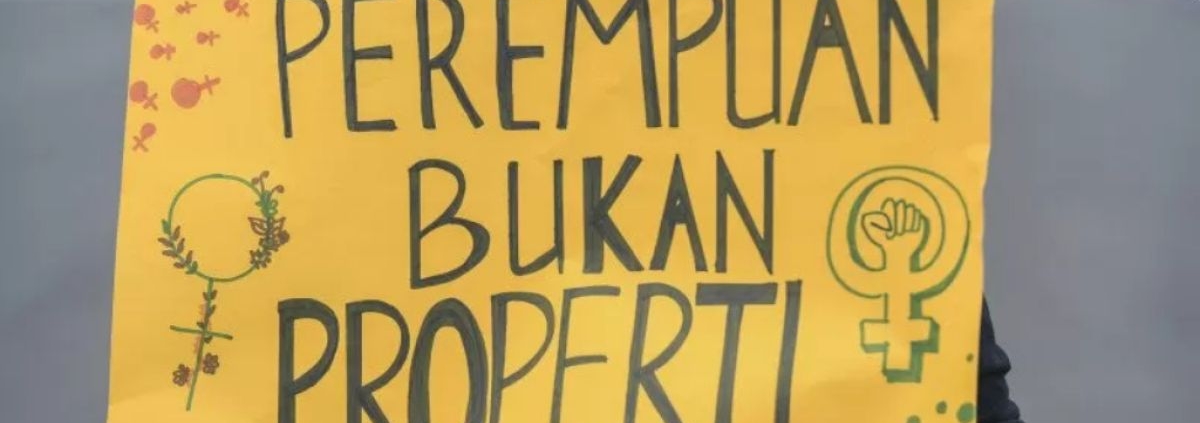

There were 18,000 reports of violence in Indonesia from January 1 to September 2023. Women were the victims in 16,000 of these cases. Photo by Hafidz Mubarak for Antara.

In September, a 24-year-old Bekasi mother of two was murdered by her husband. Her post-mortem revealed horrific violence.

It was not the first time her husband had physically abused her. A month earlier, she had reported his violence to police, undergoing a medical examination to provide proof. But the police did not act. Family members said she left home to save herself but returned for the sake of her children – her husband was unemployed and she was the bread winner.

Her neighbors heard cries for help on her last night while she was being beaten, but it was too late for police to investigate her appeal for protection.

In June, another mother of two was killed by her husband in Pati, Central Java. The 31-year-old died from her wounds in bed, hugging her two malnourished children, aged two and four.

Her husband was the first to find her body but neighbors noticed the bruises all over her body and reported him to police. Just a week before she died, her father had visited her. She had broken down and showed him her bruises in a plea for help. But, like the Bekasi victim, she was left to fight for her life alone.

Indonesia is failing to protect women and children

These stories point to a dysfunctional system. According to data from the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection, there were about 18,000 reports of violence in Indonesia from January 1 to September 2023. Women were the victims in 16,000 of these and around 11,000 cases related to acts of domestic violence.

The ministry says young women and women in unregistered marriages are at a higher risk of experiencing domestic abuse. There is also a high risk of domestic violence in households where the husband has more than one wife. Women with unemployed partners or partners with a history of substance abuse are likewise more vulnerable to domestic violence.

A national survey conducted by the ministry recorded 18% of married women as experiencing physical or sexual violence. Furthermore, 21% of married women reported experiencing emotional violence, while 25% had experienced economic violence, where the husband exploits or depletes a partner’s assets.

These statistics paint a bleak picture.

The government has the legal authority to act

The failure of the Indonesian government to protect women and children is not due to a lack of legislative power.

Since Independence in 1945, Indonesia’s women’s movement has advocated for legal protection, and in the Soeharto Era, Indonesia enacted the Law on Marriage (no. 1/1974) and ratified two key United Nations conventions – the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 1984 and the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990.

Likewise, the Law on Child Protection (no. 23/2002) and the Law on the Elimination of Domestic Violence (no. 23/2004) were passed under the administration of Indonesia’s first female president, Megawati Soekarnoputri.

Her successor, President Susilo Bambang “SBY” Yudhoyono enacted the Elimination of Human Trafficking Law (no. 21/2007) and the Juvenile Justice System Law (no. 11/2023) and also amended the Child Protection Law.

Since taking office in 2014, President Joko Widodo has further strengthened legal protections, amending the Child Protection Law to impose harsher punishments on sexual offenders, and passing the Law on the Elimination of Sexual Violence (no.12 2022) last year to better protect vulnerable groups.

Yet despite all these legal accomplishments, women and children are still exposed to widespread violence and abuse in Indonesia.

Advocates need to address gender roles

So where has Indonesia gone wrong in protecting women and children from domestic violence? Kate O’ Shaughnessy argues one problem is the law does not properly address ideological, religious and cultural definitions of gender roles.

Specifically, the Law on Marriage (no.1/1974) in Indonesia states that a husband and wife are equal. Nevertheless, Article 31(3) of this law identifies a family structure where “the husband is the head of the family, and the wife takes care of the household.” This designation of roles still ties women to homemaking and motherhood.

Despite commendable progress in other areas, legislators have failed to update the narrow underlying role of women as defined by the Marriage Law – and this had a big impact on the treatment of women.

Although a National Gender Mainstreaming Policy has been around for two decades, women are still grappling with the existence of widespread religious and cultural practices that discriminate against them. At an individual level, for instance, researchers in Nusa Tenggara Barat found that women showed only a basic understanding of what constitutes domestic violence, while in underprivileged families, domestic violence is still widely considered a private matter.

Where to from here?

Clearly, Indonesia still has a long way to go to protect women and children from domestic violence. Law enforcement must do better at investigating reports of domestic violence and providing protection to women and children.

But with a vast archipelago comprised of many diverse cultures, the government currently lacks sufficient staff and resources to do this.

It has also become challenging to revise legislation – like the Marriage Law – that touches on religious sensitivities now that religious pressure groups are increasingly shaping the content and interpretation of laws.

However, hopes were raised in 2017 when the Constitutional Court increased the minimum age of marriage for women. This came after three survivors of child marriage shared their stories of abuse before the court.

Previously, Article 7(1) of the Marriage Law set the minimum age of marriage for men at 19 and women at just 16. The issue of gender equality was examined before the court, with experts and relevant religious and non-religious institutions testifying. In its decision, the court ordered the minimum age of marriage to be made equal for men and women, at 19.

More wins like this are needed. Continued advocacy for the reform of gender roles in legislation is essential if Indonesia is ever to overcome the problem of violence against women and children.

https://ambon.antaranews.com/berita/190443/fakta-menarik-tentang-coldplay

https://ambon.antaranews.com/berita/190443/fakta-menarik-tentang-coldplay