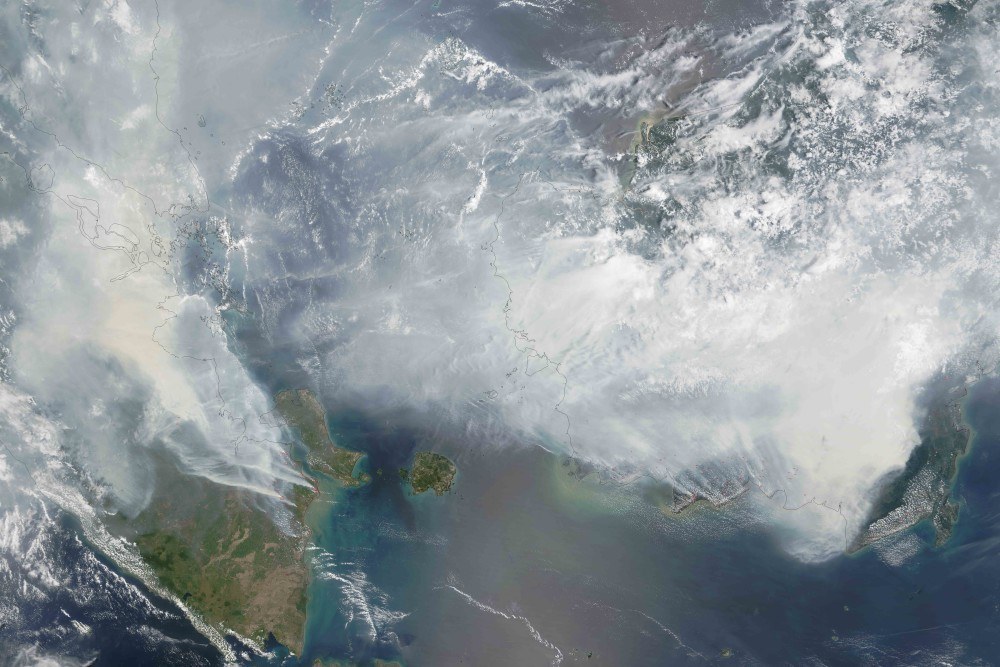

Smoke covering most of Kalimantan and the southern part of Sumatra. Preventing the conditions that allow fires to catch and spread so easily will require improvements to land governance and law enforcement. Photo by Adam Voiland (NASA Earth Observatory) and Jeff Schmaltz (LANCE MODIS Rapid Response).

A state of emergency was announced in parts of Sumatra and Kalimantan last month as haze from agricultural fires exceeded hazardous levels. Clearing forest cover and draining peatlands for palm oil and pulp and paper plantations makes peatlands highly flammable and difficult to extinguish if they catch fire. The powerful El Nino phenomenon the world is experiencing is the strongest since 1997 (which at the time triggered the worst haze Southeast Asia has ever seen) and is causing tinder dry conditions that will prolong the burning season.

At least 138,000 hectares of land have already been ravaged by fire in Kalimantan. In Sumatra, 52,000 hectares of land has been burnt. The areas most affected by haze are Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, Central Kalimantan and West Kalimantan, where the air pollution index has surpassed levels dangerous to human health. Hundreds of thousands of people have contracted respiratory illnesses. Abroad, the haze has once again enraged Indonesia’s neighbours, Singapore and Malaysia, where schools have been closed and flights grounded.

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has deployed 3,700 military and 7,900 police officers to fight the fires. Cloud-seeding operations have been used in Riau and Jambi but a lack of suitable clouds in Kalimantan has limited this option there. Indonesian authorities have predicted that it will take a month to bring the fires under control.

With public frustration over government inaction growing, the national newspaper Republika took the extraordinary step of covering its front page in “haze” on Thursday.

#HEADLINE #HarianREPUBLIKA | Saat TERTUTUP ASAP, semua berita menjadi sulit dibaca… #MelawanAsap @jokowi @Pak_JK pic.twitter.com/yDMLB301NR

— Republika.co.id (@republikaonline) October 8, 2015

Despite initially declining overseas support, Jokowi announced later that day that he had asked Australia, China, Japan, Malaysia and Singapore to help with fire-fighting efforts.

Government officials in Riau, a haze epicentre, say that it is likely that the fires were intentionally lit. Most of the hotspots are within concessions of industrial palm oil and pulp and paper plantation companies – 37 per cent of the province’s 4.6 million hectares of peatland is occupied by large plantation companies. In neighbouring Jambi, 80 per cent of the fires in the province are located within palm oil and timber (hutan tanaman industri) concessions, according to the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi) in Jambi. Smallholders play a role also, according to Indonesia’s disaster management agency, as laws allow up to 2 hectares of land to be cleared for small plantations.

But the complex nature of peat systems means identifying the perpetrators of agricultural fires is no easy feat. As peat systems cover large underground areas, fires often spread some distance underground, invisible to the eye, before appearing above ground. CIFOR director-general Peter Holmgren says: “Figuring out what one particular hotspot actually indicates, what the activities on the ground have been and are, who are doing it on the ground, who is carrying out the investment behind that land conversion, and why aren’t the authorities more active in dealing with that particular fire, is a very tedious investigation.”

Preventing the conditions that allow fires to catch and spread so easily will require serious improvements to land and forest governance and law enforcement. The sector is plagued by problems such as overlapping or unclear regulations, lack of accurate maps, unclear land tenure and uncertain land classification, and limited transparency or public involvement in decisions over the allocation of land use permits.

The haze has at least elicited a long overdue response by law enforcement officials. Police report they are investigating 238 cases of agricultural fires, including 47 companies, with 11 corporate executives declared suspects. The Plantation Law (Law No. 39 of 2014) sets out punitive measures for companies found guilty of using fire to clear land for plantations, including fines of Rp 10 billion and up to 10 years imprisonment. In addition to the 11 executives, police have arrested 205 other individuals. Most are farmers, however, and are not officially linked to industrial plantations or their suppliers. This creates concern that the root causes of Indonesia’s forest and land clearing issues will remain unaddressed.

The Singapore government has launched legal action against Indonesian companies, enacting the Transboundary Haze Pollution Act, which was finally ratified by Indonesia in 2014 after years of foot-dragging. The law allows Singapore to fine companies from S$100,000 a day to a maximum of S$1.95 million. Five Indonesian companies – Rimba Hutani Mas, Sebangun Bumi Andalas Wood Industries, Bumi Sriwijaya Sentosa, Wachyuni Mandira and Asia Pulp and Paper – have been told to take measures to extinguish fires on their land, refrain from starting new fires, and submit action plans to prevent future fires.

A landmark Supreme Court case announced last month also offers some hope for more effective law enforcement. The Supreme Court upheld a ruling against Indonesian palm oil company PT Kallista Alam, which was found guilty of deliberately using fire to clear peatland in Aceh in 2012 and fined Rp 366 billion (about AU$36 million).

Civil society organisations are capitalising on the momentum of this victory to sue the Indonesian government for suffering caused by the haze. Walhi is preparing a class action, bringing together affected citizens in Jambi, Riau, South Sumatra, Central Kalimantan and West Kalimantan to act as plantiffs. In West Kalimantan alone, 100 families have submitted identity cards to join the class action. Should any of these claims succeed, it will send a strong message to plantation owners, forestry and law enforcement officials that unsustainable land use practices will no longer be tolerated.

Even so, palm oil’s contribution to Indonesia’s economic growth and the large and growing global demand for it mean that the core issues underpinning the haze problem will not go away. Strengthening land governance is therefore vital to avoiding future burning seasons.

Improved land licensing, including ensuring that areas of deep peat and biodiversity rich forests are not allocated for conversion to plantations, is key to resolving the underlying causes of the haze issue. Encouraging more sustainable land use practices will involve supporting community involvement in forest and land management and providing tenure security for landholders through improved spatial plans. Enhanced monitoring and increased transparency and public participation in all stages of decision making related to land use will also help to undermine the networks of elites who influence land-use decisions.

These are all big tasks. But Indonesia can be sure that the haze problem will return if they are not addressed.