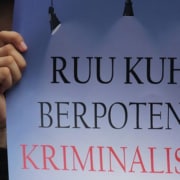

Students protesting against the draft revised criminal code (RKUHP) on 28 June 2022. Photo by M Risyal Hidayat for Antara.

Almost three years after widespread student and civil society protests put the brakes on deliberations, Indonesia’s controversial new revised criminal code (RKUHP or RUU KUHP) looks close to being passed.

After initially refusing to release the draft code, the government finally made the latest version public on 6 July, delivering it to the national legislature (DPR). The government and legislature have now agreed to focus on just 14 problematic issues that the government believes had a role in sparking the massive #ReformasiDikorupsi (#ReformCorrupted) protests in 2019 that ultimately led to President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo shelving the draft bill.

But the National Alliance for Criminal Code Reform, a coalition of concerned civil society organisations (including the Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR), with which we are affiliated), has stressed that the problems with the RKUHP are not limited to these 14 subjects. In fact, the alliance has been highly critical of the draft code’s potential to restrict freedom of expression and association, its overlap with existing criminal laws, and the closed and rushed nature of government deliberations.

In the face of growing public and civil society disquiet, Jokowi has now called on his ministers to undertake a “massive” discussion of the RKUHP with the public. This surprising but welcome move has once again opened the door for serious debate and revision of the controversial bill’s potentially damaging aspects.

What needs to happen to get the existing draft right? There are many major problems with the draft bill as it stands, for example, the code’s approach to living law, obstruction of justice, drug offences, and harmonisation with the new Law on Sexual Violence, but here we focus on just four – defamation, the death penalty, treason and the crime of “indecency”.

Defamation

Undoubtedly one of the most concerning aspects of the draft code is its expanded provisions on defamation. The government has claimed that criminal defamation provisions are necessary to protect the reputations of both individuals and the government. But such provisions raise major concerns about freedom of expression. Balancing these interests is crucial.

Ideally, defamation provisions should be dropped from the draft criminal code altogether and regulated under the civil code instead. But in the face of government obstinance, compromise looks like the most achievable means to minimise harm for now – and there are certainly ways to amend the draft articles to ensure that the public is better protected.

For example, Article 437 prohibits making oral or written statements in public that damage an individual’s reputation. The article notes that such statements are not considered an offence if made for the public interest or in self-defence. To clearly differentiate between defamation and legitimate expression, the new penal code should introduce another exemption – the defence of truth. Many other countries, including the Netherlands, include such a defence in their criminal defamation provisions.

Following widespread criticism, the government has stressed that defamation of the president and vice president, or of the government, state institutions, or public authorities, will now be a ‘complaint offence’ (delik aduan), meaning that the subject of the defamation must lodge a complaint with police if charges are to be brought. In the case of defamation of the government, the latest draft states that such defamation must also result in riots for an individual to be charged.

The government has tried to claim that these alterations mean the defamation provisions are now different to previous provisions on insulting the president and government that were struck down by the Constitutional Court in 2006 for being inconsistent with Indonesia’s democratic constitution.

Regardless of the government’s excuses, criminal provisions prohibiting insulting the president or government have no place in any democracy. The president and government should be prepared to receive any kind of criticism as an intrinsic part of holding public office. If the government really means to “decolonise” the current Criminal Code, as it claims, these prohibitions should be abandoned at all costs.

But given the government appears insistent on retaining criminal defamation protections for holders of public office, the threshold for bringing charges should be raised higher still, to protect the public’s right to criticise the government. The offence could be reformulated so it is clear that “making false accusations” that result in riots is considered sufficient to bring charges, but merely “making a degrading statement against the government” is not, even if it causes riots too.

Moreover, the understanding of “state institutions” should be limited to only those institutions listed in the Constitution, such as the national legislature (DPR), Supreme Court, Constitutional Court, and so on, to prevent any of the hundreds of any other government bodies from making a complaint.

The draft code also needs to clearly specify who has the authority to make a complaint on behalf of the institution claiming to be defamed, to avoid confusion. Ideally, only the highest officer in the relevant institution would have the authority to make a written complaint, and this power would be non-transferable.

Finally, the government should merge all provisions on defamation of state institutions (Articles 218-219 on defamation of the president and vice president; Articles 240-241 on defamation of the government; Articles 351-352 on defamation of state institutions; Article 445 on defamation of public authorities) under a single article to further minimise confusion. The Netherlands has also done this, under Article 267 of its Criminal Code.

Death penalty

Despite rapidly declining support for the death penalty, the government and members of the DPR have insisted that it must be retained in the new criminal code.

However, the new draft describes the death penalty as “special” punishment that can only be handed down as an “alternative” for certain serious crimes, such as drug-related offences, terrorism, premeditated murder, and grave violations of human rights.

Moreover, under Article 100 of the new draft, judges may hand down the death penalty with a 10-year “probation period” if: a) the offender shows remorse or hopes for rehabilitation; b) his or her role in commission of the offence was not significant; or c) other mitigating factors exist. Following this 10-year period, the death penalty may be commuted to a life sentence if the inmate demonstrates good behaviour.

This is better than the current situation. But Indonesia should go one step further and make sure that this 10-year period is automatically applied for any offender charged with the death penalty. This would help to minimise the potentially negative effects of providing judges with considerable discretion in deciding death penalty cases, given problems like judicial corruption and significant stigma toward specific offences like drug offences.

Ideally, if implemented, this 10-year probation period should also be retrospectively applied to the hundreds already on death row. By doing this, the new criminal code would constitute a major step toward protecting the life of the prisoners.

To further limit potentially negative outcomes, the new code should also provide indicators for judges about when to hand down the death penalty. If the death penalty is truly to be a “special” punishment, then it should be handed down only if the crime is “of extreme gravity, involving intentional killing”, as stated in General Comment 35 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Indonesia ratified in 2005. In fact, this document explicitly prohibits the use of the death penalty for crimes not resulting directly and intentionally in death, such as corruption and drug-related offences. Several crimes in the RKUHP do not meet these conditions (such as Articles 616, 617, and 619 on drug-related offences).

The role of the defendant, the number of victims, and method by which the act was performed should also be included as considerations in death penalty sentencing. Adopting these additional requirements could create a better balance between the abolitionist and retentionist views the draft code seeks to accommodate.

Treason

A longstanding problem with treason provisions in Indonesia has been a problem of translation. When the Dutch Criminal Code, the Wetboek Van Strafrecht voor Nederlandsch Indie (WvS), was adopted as the Indonesian Criminal Code (KUHP) in 1946, the word aanslag (“assault/onslaught”) was translated as the much more loosely defined word makar (treason).

Treason provisions have repeatedly been used to target activities that the government labels separatism or against individuals with different political views. In 2005, this article was used to imprison Christine Kakisina, who was simply serving food during a prayer session held by the secessionist Maluku Sovereignty Front (Front Kedaulatan Maluku).

Drafters of the new code have ensured that these serious problems with implementation will remain, as they have simply copied and pasted the treason provisions from the existing code. The new draft fails to clearly define what constitutes “treason”, meaning that abusive practices can continue into the future. These problems could be avoided by simply rectifying the misleading translation of aanslag, and ensuring it is translated as “assault” (or violent attack) rather than the vague term makar.

Indecency

The draft code has been rightly criticised for intruding too far into the private lives of citizens, attempting to penalise cohabitation of unmarried men and women and outlaw extra-marital sex. But another pressing “morality” issue in the draft code that has thus far received little attention is its regulation of so-called “decency” (kesusilaan).

In Indonesia, indecency is prohibited under the Criminal Code, the Pornography Law (No. 44 of 2008), the 2008 Electronic Information and Transactions Law (as amended by Law No. 19 of 2016) – the ITE Law, and the newly passed Law No. 12 of 2022 on Sexual Violence. These laws are often criticised for containing overlapping articles, and the new draft code has done nothing to resolve this issue.

For example, under Article 45 of the ITE Law, the offence of violating decency carries a punishment of six years in prison or a fine of up to Rp 1 billion (A$95,700). Meanwhile, under Article 29 of the Pornography Law, such conduct carries a sentence of between 6 months to 12 years in prison and a fine ranging from Rp 250 million to 6 billion.

The draft criminal code adds confusion to this mess. The same act could also be punished by Article 410 of the draft code on indecency (carrying a sentence of up to one year in prison) and Article 418(1c) on publicising lewd acts (which carries a sentence of up to nine years in prison).

Putting aside questions about whether the state should be attempting to regulate morality in the first place, these provisions create serious problems for legal certainty. And given widespread corruption in Indonesia, particularly in the justice sector, this problem needs to be addressed to ensure that there is no illegal bargaining over offences or punishments. The government urgently needs to assess every article related to indecency, especially criminal provisions not in the RKUHP, and revoke them, or, at the very least, harmonise them to ensure consistency.

The problems highlighted above are only a few of the multitude of problems in the RKUHP. Issues like treason and indecency are serious concerns but are not even included in the government’s list of 14 problematic issues and have therefore failed to attract much public attention thus far.

Jokowi has offered an opportunity the public to discuss the draft. This opportunity must be taken up, and the draft carefully re-evaluated, so that Indonesia’s new criminal code doesn’t just protect the interests of the state, but also protects the rights of its citizens.