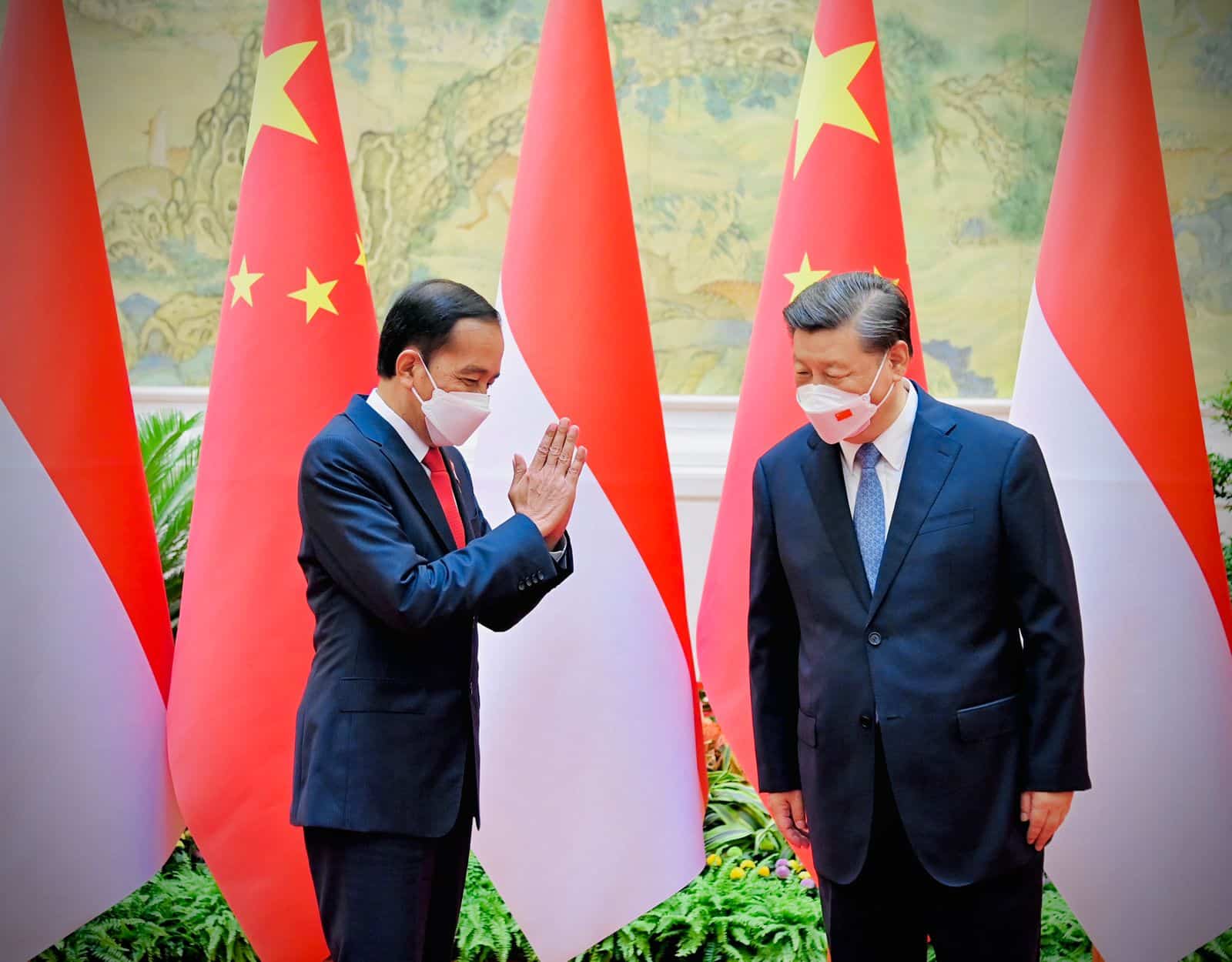

President Joko Widodo meeting President Xi Jinping in Beijing in July. Photo by BPMI Setpres/Laily Rachev.

Over the past several years, increasing attention has been paid to China’s growing political and economic foothold in Indonesia. But one area that has received comparatively little attention is the extent to which Beijing has also expanded its media influence in the country. A recent Freedom House report (of which I was an author) showed that China’s media efforts in Indonesia have increased significantly since 2019.

The purpose of these efforts is to “tell China’s story” and ensure that the narratives in the countries where Beijing has made considerable investments are in line with the interests of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

In Indonesia, China has therefore focused on rapport building, positive promotion of China, and countering negative narratives. It has promoted Jakarta-Beijing relations as mutually beneficial, highlighted what it sees as China’s success in dealing with Covid-19, and promoted images and stories of Muslims in China living peacefully.

Expanding physical presence

In recent years, a number of Chinese media have established branch offices in Indonesia, such as Hi Indo! Channel, Xinhua, and Radio Mandarin Station. China Radio International programming also airs on Jakarta-based FM news radio station Elshinta in Bahasa Indonesia. The radio station’s Indonesian service also has a Facebook page in Bahasa Indonesia with 224,000 followers.

Some of these media outlets also have social media accounts in Bahasa Indonesia. The most notable is Chinese-state media Xinhua, which has a Twitter account with 64,400 followers. Given that Xinhua is owned by the CCP and the news it provides is in line with the CCP’s views, its Indonesian social media account is apparently aimed to ensure that Chinese narratives are conveyed “properly”.

Chinese diplomats in Indonesia also actively use Twitter to propagate their messages. The previous Chinese Ambassador to Indonesia, Xiao Qian, who served from December 2017 to November 2021, did not have a notable social media presence. However, the new ambassador, Lu Kang, opened a Twitter account in April soon after presenting his credentials to President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and has already amassed 17,000 followers.

Lu uses his Twitter to highlight positive progress in China-Indonesia relations, in Chinese, English, and Bahasa Indonesia. In one of his tweets, he responded to a US Embassy tweet stating that China’s claim in the South China Sea breached the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. He accused the US of creating tension in the region and stated that China had promoted peaceful development and cooperation between countries.

Inviting journalists to China and cooperating with Indonesian media

Another aspect of China’s media strategy has been to invite journalists to visit China. In 2019, 10 Indonesian journalists from Bali, East Nusa Tenggara and West Nusa Tenggara were invited to visit China to see media developments in Beijing, Wuyuan and Nanchang. The purpose of the invitation was to increase media cooperation between the two countries, especially in reducing the spread of what China considers “fake news.”

In the same year, after news on China’s discrimination against Uyghurs spread around the world, three Indonesian journalists, along with leading figures from Muhammadiyah, Nahdlatul Ulama, and the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), were invited to visit Xinjiang on guided tours of the camps to “see the real living conditions of the Uyghurs, including in expressing their religion.”

Earlier in 2018, the Indonesian Journalists Association (PWI) attended the Belt and Road Journalist Forum Conference organised by the All-China Journalists Association (ACJA) and supported by China Communications University and China International Radio. At the conference, China and Indonesia signed a memorandum of understanding on journalist exchanges, journalist training, joint reporting and academic activities. ACJA and PWI even created a prize for Indonesian journalists writing on the Belt and Road Initiative, effectively incentivising local journalists to write pro-Beijing propaganda.

Aside from journalists, China has also invited Indonesian social media influencers to China. Tenggara Strategics, an Indonesian investment research and advisory institute that helped organise a tour in September 2019, said that influencers were paid a per diem of $500 and were not subject to overt censorship.

One tour participant, former Miss Indonesia Alya Nurshabrina, posted a now-deleted photo of a mosque outside Beijing, telling 86,000 Instagram followers that “China welcomes every religion”. On 1 October 2020, Nurshabrina posted a series of photos showcasing her positive experiences in China and promoted a competition in which she called on her followers to share their own experiences in China.

Besides inviting journalists and influencers to China, Chinese media entities have also established ties with their Indonesian counterparts. In 2015, for example, Xinhua signed a cooperation with Antara on “eradicating fake news”. As a result of the Xinhua-Antara agreement, Antara TV Indonesia sometimes broadcasts positive documentaries about China on its YouTube channel. A content-sharing agreement has also been established with The Jakarta Post, where content from Chinese media such as Xinhua and China Daily are reposted.

China has also cooperated with MetroTV. It offers programming from CGTN, the Chinese government’s English language news channel, and hosts Metro Xinwen, a Chinese-language entertainment and news shows that promotes China positively. The daily newspaper Media Indonesia (which shares the same owner as MetroTV) also publishes content from Xinhua.

Research published in The British Journal of Chinese Studies by Senia Febrica and Suzie Sudarman from Universitas Indonesia has also confirmed that Indonesian media that repost Chinese media reports often choose news with positive representations of China.

Censoring and intimidation

China has also made efforts to counter anti-China information in Indonesia. In August 2020, Reuters reported that the Chinese tech firm ByteDance had censored articles critical of the Chinese government on its Baca Berita (BaBe) news aggregator app, which is used by millions in Indonesia. The censorship occurred from 2018 to mid-2020, and was based on instructions from a team at the company’s Beijing headquarters.

The restricted content reportedly included references to “Tiananmen” and “Mao Zedong”, as well as to China-Indonesia tensions over the South China Sea and a local ban on the video-sharing app TikTok, which is also owned by ByteDance. Conflicting reports from the company and sources cited in the article claimed that the moderation rules became less restrictive in either 2019 or mid-2020.

However, in early 2021, the Chinese government censorship agency blocked Indonesian newspaper site Jawa Pos in several regions in China, including Beijing, Shenzhen, Inner Mongolia, and Yunnan. According to research by Jawa Pos, the blocking was allegedly due to China’s sensitivity to criticism of the CCP and the issue of violations of the human rights of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

There is also some evidence that the Chinese state has sought to intimidate individual Indonesian journalists. Bayu Hermawan, a journalist for Republika, a national daily newspaper for Indonesia’s Muslim community, received a WhatsApp message from a Chinese embassy employee in Jakarta saying that an article he wrote about a 2019 Beijing-organized tour to Xinjiang contained errors and did not properly acknowledge the positive aspects of his trip.

Difficulties

Despite all this, China’s media strategy in Indonesia has not always run as smoothly as it perhaps hoped. While some media have established ties with China, these media also publish pieces that are critical of China.

Indeed, it is difficult to draw broad conclusions about the media in Indonesia. For one, it is often influenced by domestic politics. Media that are supportive of the current government (which has strong ties with China) seem to view China positively, while those affiliated with opposition figures often criticise the government’s policies, including its close ties with China. But this may shift according to domestic political dynamics. Further, many local China experts remain critical of China, and they are often invited to offer their opinions in the media. This balances the positive depictions of China described above.

As a democratic country, Indonesia needs to ensure that Chinese media influence does not pose a threat to its democratic freedoms and structures. It should therefore engage academic and research institutions to carry out research on China’s media strategy in the country.

Local media also need to improve their awareness of the potential journalistic and political pitfalls of accepting Chinese media agreements. Indonesian journalist associations and media owner groups need to be more careful when signing content-sharing partnerships and MoUs with Chinese state-media entities or government-affiliated groups like the All-China Journalists Association.

As the International Federation of Journalists recommends, Indonesian journalist associations and media owner groups should supplement journalist trips to China with training on China’s media strategy, and common false or one-sided narratives, while facilitating encounters with victims of persecution from China. These associations should also uphold journalistic codes of ethics by encouraging members to be transparent regarding articles commissioned by Chinese embassies, sponsored content, and sources of funds for travel to China that results in published news items.

While China’s efforts do not yet appear to have made a significant impact on public attitudes in Indonesia, it is clear that given the extent of its efforts, a lot more caution is needed.