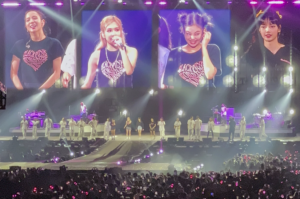

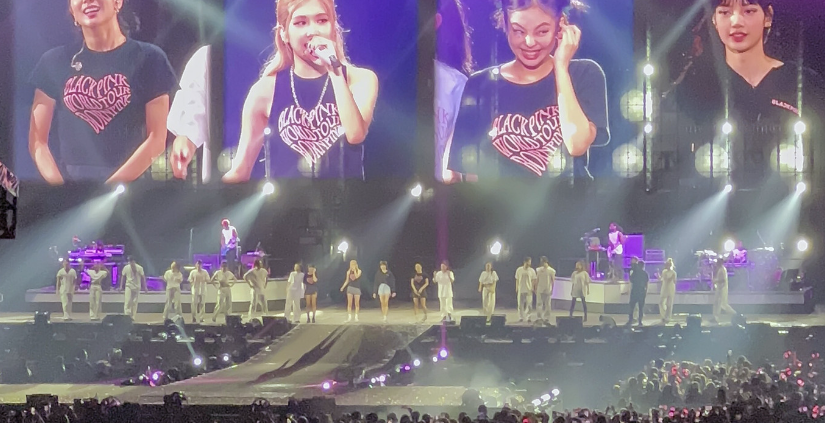

The K-pop group Blackpink performing at Bung Karno Stadium in Jakarta on 11 March 2023. Photo by Rianti for Antara.

Indonesia’s General Election Commission (KPU) has revealed that a majority of voters in the upcoming presidential election will be young people. In fact, millennials and Generation Z will constitute 60 percent of the total electorate in 2024.

Unsurprisingly, this is having a significant impact on the campaign strategies employed by candidates compared to previous years. Social media has become the key battle ground as candidates try to curate and amplify their image with younger voters.

Nowhere is this changing online campaign landscape more evident than presidential candidate Anies Baswedan’s recent foray into K-pop fandom through the X (Twitter) account Anies Bubble.

K-pop Fandom in Indonesia

The influence of fan cultures on the political discourse in Indonesia is often overlooked. Fans are perceived as delusional and obsessive, which has limited their relevance for political strategists seeking broad appeal.

However, the political influence of K-pop in Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries is rising and should not be underestimated. The spread of the so-called Korean Wave (or Hallyu) since the late 2000’s has given Indonesia arguably the largest K-pop fan base in the world.

Their large numbers – and devotion – have made Indonesian K-pop fans a powerful force on social media. According to a 2021 Twitter report, Indonesia is now the number one source of discussion on K-pop in the world.

K-pop fans are able to leverage their social media prowess and obsession with their idols to advocate for change and social impact. During the pandemic, for example, K-pop fans were among the most active fundraisers on the donation platform Kitabisa. The Indonesian BTS Army, the fandom of the hugely popular K-pop boy band BTS, raised Rp 447 million for the victims of the Kanjuruhan stadium disaster in 2022, which reportedly killed 135 people.

But K-pop fans are also increasingly voicing their discontent. They were, for instance, vocal opponents of the Indonesian government’s controversial Omnibus Job Creation Law in 2020. They have also advocated for peace in Palestine and supported online fundraising efforts.

Anies riding the K-pop wave

It’s no wonder Indonesian politicians are starting to capitalise on K-pop hysteria – including through the curious Anies Baswedan fan account that recently emerged on X: ‘Anies Bubble’. The account provides detailed information about Anies Baswedan’s campaign, presented in the style of a K-pop super fan (i.e. stan) account.

The account shares video snippets of Anies’ campaign events complete with flattering Korean language commentary. Despite only launching in December, the account has already captured the attention of 140 thousand followers and has trended on X several times.

Thanks to Anies Bubble, Anies has gained the Korean nickname ‘Park Ahn Nice’, while his running mate, Muhaimin Iskandar, has been dubbed Cha I Min, a play on his nickname Cak Imin. Bubble followers suggest Anies has the endearing persona of ‘bapak-bapak gaptek’ – meaning ‘clueless dads’.

Anies Bubble – through a spin-off called Project Olppaemi – has even been helping out with offline campaigning by installing several videotron screens around the country. Regional governments in some cities have already had these removed.

A spokesperson for Baswedan denied claims Bubble account is a creation of his campaign team, insisting the fan account is simply an organic result of Anies’ more relatable TikTok content.

The account certainly offers welcome publicity for Baswedan, who has been actively projecting a softer image since his association with religious hardliners in the controversial 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial elections tarnished his appeal with younger secular voters.

The rise of online gimmicks

Anies is not the only one trying to relate better to younger voters. The size of the Gen Z voter pool in 2024 is undoubtedly concentrating campaign efforts towards superficial online gimmicks.

The Prabowo Subianto – Gibran Rakabuming camp stands out for their strategy to market Prabowo as a ‘gemoy’ (cute, adorable) grandpa figure to online netizens. The Prabowo camp is currently the presidential candidate with the largest social media budget and has excelled at creating content for TikTok, a favourite platform of Gen Z voters. His camp is well versed in the world of modern tech gimmicks, like the AI-generated Disney-style character animations his campaign is using widely

This more personal campaign strategy employed by the Prabowo camp has drawn comparison with the approach of Bongbong Marcos and Sara Duterte, who won the Philippines presidential election in 2022.

Although effective in building popularity, judging by Prabowo’s widening lead over the other two candidates, this method has also become a distraction from substantive policy discussions, questions over Prabowo’s past human rights violations and the controversial constitutional court ruling that allowed Gibran to become his running mate – and that is probably precisely its purpose.

In contrast though, the Ganjar Pranowo – Mahfud MD candidacy has been the more conventional in their campaign approach. Ganjar’s method of grassroots ‘blusukan’ community visits, popularised by Jokowi, remains unchanged despite Jokowi’s endorsement of Prabowo.

The emergence of the @aniesbubble account and a new ‘clueless dad’ persona certainly helps Anies Baswedan counter Prabowo’s successful ‘gemoy’ strategy. It also represents an innovative campaign model for leveraging an organic (or supposedly organic) online following. Rather than relying on the one-way messaging of traditional campaigns, fan accounts can build buzz and make candidates appear more relatable.

Leaning in to bubble and other K-pop fandom, with its organic reach and optimistic tone, will likely help Anies win the hearts of Indonesia’s K-pop fans, an increasingly important demographic.

However, elections are ultimately about votes – can Anies convert his K-pop success to picks at the ballot box? Or will his K-pop superfans drive off some mainstream voters?

Perhaps the bigger question though surrounds the long-term implications of superficial online campaign strategies. Do fan accounts like @AniesBubble really contribute to a healthy democratic discourse – or do they risk trivialising Indonesia’s already fragile democracy?

https://www.flickr.com/photos/djou/6521912409

https://www.flickr.com/photos/djou/6521912409