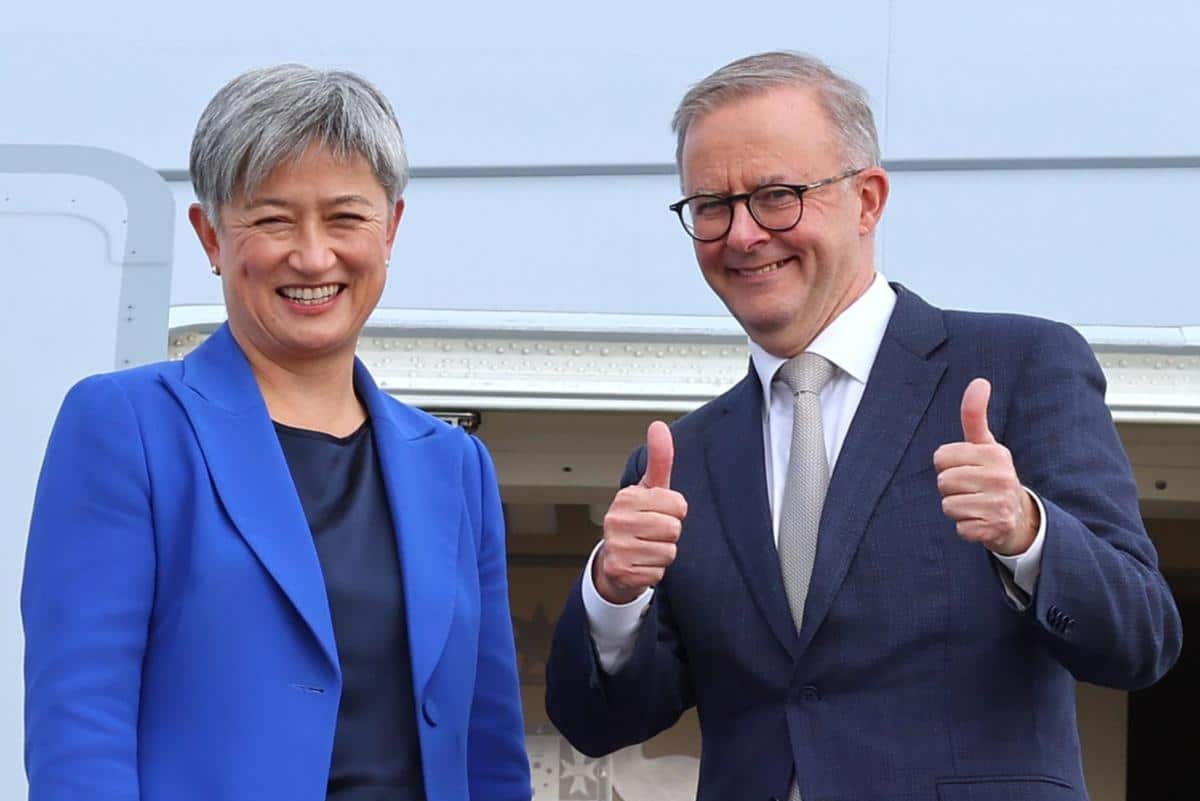

New Foreign Minister Penny Wong and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. Photo by The West Australian.

On 23 May, Anthony Albanese was formally sworn in as the 31st prime minister of Australia.

A few hours later, he embarked on his first foreign trip, to attend the Quad leaders’ meeting in Tokyo. There, he and new Foreign Minister Penny Wong held bilateral meetings with Australia’s closest allies. On returning to Australia, Wong immediately left for another trip, to Fiji, to reassure Pacific countries that Australia was now serious about addressing climate change.

Albanese has previously pledged to prioritise ties with Indonesia and it is likely that his next trip will be to Jakarta. His remarks at the Quad meeting also included a commitment to ASEAN centrality, a longstanding concern for Indonesia.

With the Albanese government now attempting to reboot Australia’s foreign policy, it is important to consider how it might go about improving Australia’s relations with Indonesia. How can Albanese and the new Labor government build a relationship of trust with Indonesia in this age of great power rivalry, especially in the Indo-Pacific?

Australia has made considerable efforts to forge closer relations with Indonesia over the last two decades. The two countries signed the Lombok Treaty on security cooperation in 2006, and this was followed by a “Joint Understanding” on its implementation in 2014, and a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) in 2018. Then in 2020, after years of negotiations, the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IA-CEPA) was passed. President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo even came to Canberra in February 2020 and gave a speech to Parliament to mark the ratification of this long-awaited free trade agreement.

These security and economic commitments have given Albanese a good base of foreign policy and diplomatic engagement for further deepening the Australian relationship with Indonesia. He will not need to start from zero. Nevertheless, the Australia-Indonesia relationship has historically been characterised by occasional tensions and mistrust between the two countries.

The AUKUS case is illustrative. When it was announced in September 2021, Indonesia was critical of the agreement, and emphasised the Southeast Asian commitment to remaining a nuclear weapon-free zone. But Indonesia’s concerns did not just relate to Australia’s procurement of nuclear-powered submarines. They were also connected to the fact that Indonesian and Malaysian leaders were not informed about AUKUS, undermining trust and underlining past tensions.

If the new Australian government is to establish trustworthy relations with Indonesia, more understanding and engagement will be key. Two aspects, in particular, should be considered by Albanese and his foreign policy team in rebuilding relations with Indonesia.

First, Australia needs to accept that Australia and Indonesia have different foreign policy orientations and objectives and, in particular, that Indonesia – like other Southeast Asian countries – has a different vision of the Indo-Pacific regional order to Australia. Indonesia’s perception of the regional order is focused less on creating a free and open Indo-Pacific than it is on maintaining strategic autonomy and regional stability amid growing fears of great power rivalry.

Likewise, Australia also needs to understand that Indonesia also has different perspectives and approaches toward China, some of which will not be shared by Australia’s foreign and security policy establishment. It will be important not to frame the relationship with Indonesia in the context of US-China competition, which could exacerbate the divide between Australia and Indonesia in their approach to the Indo-Pacific. Albanese needs to convince Indonesia (and other Southeast Asian countries) that Australia is a credible partner for safeguarding regional stability in Southeast Asia.

Nevertheless, there are also some areas where Indonesia and Australia do converge, such as Pacific diplomacy. For example, in recent years, Jakarta has launched its Indonesian Aid international development agency and “Pacific Elevation” strategy as part of its increasing engagement with Pacific counterparts. With Australia now refocusing its diplomatic efforts on the Pacific, these programs offer potential areas for cooperation.

Second, it is important to cultivate trust between Australia and Indonesia – not just between political leaders but also among civil society and the public. While both Albanese and his predecessors have emphasised the importance of engaging with Indonesia, this has not always translated into serious efforts to strengthen people-to-people engagement.

There is considerable misunderstanding and distrust among the citizens of both countries. For example, a 2016 survey found that 47% of Australians had unfavourable views of Indonesia. Similarly, in 2020, 58% of Australians disagreed that Indonesia was a democracy.

On the other hand, Lowy Institute polling conducted in 2021 found that Indonesians’ trust in Australia has fallen dramatically over the past decade – only 55% of those surveyed expressed trust in Australia, a drop of 20 points from 2011. There was also very little understanding of Australian foreign policy. For example, less than 10% of Indonesians had heard about the Quad and only 11% knew about AUKUS.

Building trust must therefore go beyond government-to-government or business-to-business cooperation. Albanese needs to encourage mutual learning between the Indonesian and Australian publics and make efforts to overcome ethnic and religious barriers that can sometimes complicate collaboration between the two countries. For example, Albanese needs to change simplistic views of Indonesian Islam among Australians and introduce more Australians to the many “moderate” Muslim communities in Indonesia.

The same could be said for Indonesian leaders, who also need to change Indonesians’ misunderstandings of Australia and encourage broader people-to-people connections.

One way to begin encouraging people-to-people understandings is to support Indonesian language in Australian universities. The decline in the study of Indonesian language and culture at Australian universities over the past two decades has been widely reported. The Albanese government urgently needs to invest in Indonesian language training in Australian high schools and universities, which is crucial to improving the people-to-people relationship.

Moreover, Albanese should encourage greater mobility of Indonesians to Australia. There is reason to be hopeful here – at a meeting with Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi in 2019, Albanese called for more Indonesian tourists to Australia. He could make this happen by revisiting Australia’s strict visa requirements and offering more opportunities for Indonesians to study and work in Australia.

Building a trustworthy relationship will require mutual engagement and understanding between both Australia and Indonesia. Albanese has committed to deepening the relationship. What is now needed are concrete efforts that go beyond the usual platitudes.