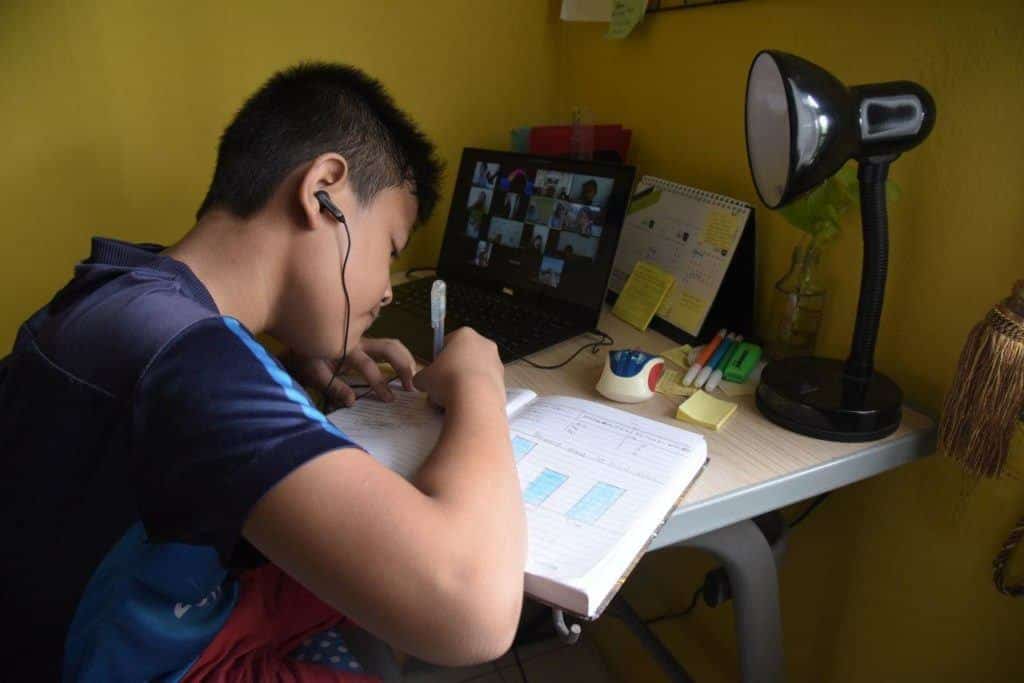

Some students are struggling with inadequate access to learning resources at home. Photo by Novita Eka Syaputri

Even before this year’s Covid-19 pandemic, Indonesian students’ academic performance lagged behind their peers in other countries. When the pandemic hit, many lost the chance to catch up, and now are at risk of significant learning loss due to prolonged school closures.

Yet learning loss does not seem to have attracted the same level of concern as economic loss. In many provinces, large-scale social restrictions (PSBB) have been cut short to prevent further economic recession. In contrast, schools have been slow to reopen because of the risk of coronavirus transmission.

In fact, the risk of learning loss deserves greater attention because prolonged school closures can lead to permanent income reduction in the future. This damage will be most severe among disadvantaged students who suffered learning inequalities before the pandemic.

Compared to their peers, disadvantaged students have inadequate access to resources for learning from home, which leaves them further behind when they return to school. In addition to socioeconomic status, learning practices also tend to be unequal.

This high level of inequality among students across Indonesia does not seem to have been anticipated by the Ministry for Education and Culture in planning its response to the pandemic. Minister Nadiem Makarim admitted in May that he had only just learned that some parts of the country do not have an electricity supply, let alone reliable internet access.

How have Indonesian students managed to study during the pandemic, and how has the distorted learning experience exacerbated existing inequalities? Can the current school reopening policy address these problems?

‘Schooling from home’ and learning inequality

Our survey and in-depth interviews from April to June with primary school teachers, school principals, and parents suggest that learning quality has varied since ‘schooling from home’ was introduced at the start of the year. This variation has produced inequalities, as certain groups of students received inadequate learning and support compared to their peers.

On the part of teachers, we found wide variation in perceptions and teaching practices. Many teachers in public schools perceived home schooling as a school holiday, and so did not hold any lessons during that “holiday” period. Other public school teachers thought that lessons should continue, but in practice only assigned students lots of homework, expecting that schools would soon reopen.

Meanwhile, private school teachers tended to perceive schooling from home as a continuation of normal learning, and prepared lessons accordingly. In urban areas, some private schools had anticipated and prepared for a home schooling scenario since the government confirmed the first Covid-19 case in March.

We found that in general, teachers in urban areas, and especially those in Java, were better at using digital applications to deliver lessons or assignments. Teachers at some private schools in Java’s urban areas reported that they tried to facilitate virtual learning in the same way as they would conduct a lesson at school. These teachers interacted with students regularly using video conferencing.

In contrast, teachers in rural areas outside Java, and especially in areas with constrained internet access, had less interaction with students and communicated with parents infrequently to discuss learning progress. Teachers in these areas had to conduct home visits to ensure that learning could continue during school closures.

Few teachers managed to teach students regularly under these abnormal circumstances. In Enrekang, South Sulawesi, one teacher reported that she had to travel an average of 30 kilometres to get to each of her students’ homes.

School support was another factor that contributed to learning variation. Teachers in urban areas of Java were more likely to receive funds from their schools to purchase internet data and receive training on how to use technology for remote teaching. Private school teachers were more likely to receive these aids than teachers in public schools.

We also found variation in students’ home environments, including the quality of parental supervision and learning resources. Children with poorly educated parents who lived in rural areas were more likely to spend their time playing than studying, and had unclear learning schedules. Moreover, children with lower economic status could not afford the technological devices and internet data needed to engage in remote learning, and so missed out on available lessons.

Options for reopening schools

A push to reopen schools has gained momentum as prolonged distance learning has proved unable to provide quality learning for a majority of students. The Ministry for Education and Culture has established programs to help disadvantaged students during school closures, yet most of these students still suffer from poor learning outcomes. Local governments reopening schools to allow in-person lessons is now the best option to prevent disadvantaged children from falling further behind.

Many parents also look forward to schools reopening. Parents with full-time jobs have expressed concerns about their ability to support their children in their studies at home. In response, the ministry first allowed schools in “green zones” (with zero confirmed cases of coronavirus) to reopen under strict health protocols in June. This was later expanded to schools in “yellow zones” (with a low risk of Covid-19 spread).

The government’s careful approach to reopening schools is understandable, yet the implementation has not been without problems. Administratively, reopening is subject to permits issued by district-level authorities. This means students can return to school only when the regional government is ready to implement the change.

In one “green zone” city in West Sumatra, schools didn’t end up reopening when a teacher tested positive for coronavirus, after the local government carried out swab tests for all teachers and school staff. In another city in the same province, students were forced to return to distance learning after two school staff members tested positive. Overall, the rate of school reopening, even in relatively safe areas, has remained low. At this rate, schools in more populated regions are likely keep their doors closed until the pandemic is well and truly over.

Instead of issuing a one-size-fits-all mechanism, the government could create more options for schools reopening. Schools could be given the flexibility to choose a scenario for reopening after meeting government health protocols. For example, a shift system could be introduced for students if all parents allow their children to return to school.

In cases where schools cannot reopen, school principals could place teachers on a rotating roster to provide direct assistance for parents or children in need. Schools also need to have a mechanism in place for parents who do not allow their children to return to school. For example, teachers could make home visits to children who live in neighbouring areas to facilitate group learning.

While the health of students and their communities is paramount, a more nuanced approach is needed that can protect students’ health as well as their futures. To prevent Indonesian students, and particularly the most disadvantaged, from falling further behind, the government must now consider options beyond prolonged school closures.

This research is supported by the Knowledge Sector Initiative, an Australia-Indonesia partnership.