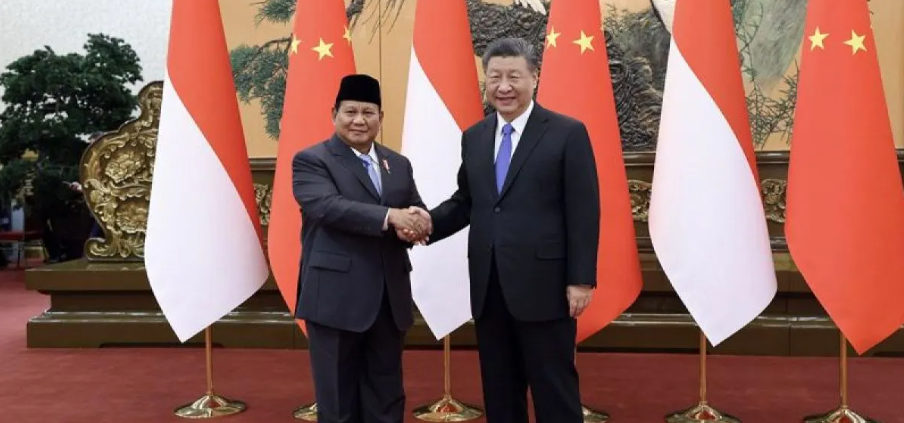

Indonesian President elect, Prabowo Subianto, met with President of China, Xi Jinping, in Beijing on 1 April 2024.

Prabowo Subianto has officially been declared the winner of Indonesia’s 2024 election. He will be formally inaugurated as president in September, now that Indonesia’s Constitutional Court has recently rejected a challenge of the election.

For foreign policy and security analysts, the daunting question following Prabowo’s election is the future direction of Indonesia’s foreign policy. On the one hand, Prabowo has vowed to continue the legacies of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo. This inevitably includes deepening Indonesia’s relationship with China, which has intensified under Jokowi.

In fact, since Jokowi came to power, China has become Indonesia’s biggest trading partner and a major source of investment. Indonesia has benefited from China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and China’s investment in the local nickel industry has been pivotal in accelerating Indonesia’s dominance in that industry. So it is not surprising that Prabowo visited China earlier this month, well ahead of his formal inauguration.

But on the other hand, Prabowo is renowned for his nationalist rhetoric and vocal defence of Indonesian sovereignty. In 2019, he criticised Jokowi for allowing large numbers of Chinese workers to come to Indonesia. He abandoned this rhetoric after being appointed as Minister of Defence, but he still maintains Indonesia needs to tighten regulations for foreign workers, the majority of whom come from China.

In addition, Prabowo has repeatedly asserted that Indonesia needs to defend its territorial sovereignty and be prepared for any future scenario by emphasising a ‘good neighbour’ policy, which he said encompasses a commitment to neutrality and non-alignment, and foreign investment and market-friendly policies.

However, this ‘good neighbour’ policy is vulnerable to China’s growing assertiveness over its maritime territorial claim in South China Sea, which has been a flashpoint for tensions with the Philippines recently. Both Indonesia and China share competing claims over territory in the Natuna Sea.

Prabowo’s China dilemma

These seemingly contradictory positions point to the dilemma that the Prabowo administration will grapple with regarding China.

Prabowo is likely to continue President Jokowi’s signature policies, including industrial downstreaming, capital city relocation and infrastructure developments. This would, inevitably, require Indonesia to strengthen its relationship with its main source of investment: China. But that would also imply tolerating the influx of Chinese workers to Indonesia – an inseparable component of Chinese investment – and position Indonesia closer to China in international politics.

Can Prabowo resolve his China dilemma?

To understand his options, we need to consider Indonesia’s current political landscape. Prabowo’s coalition with Jokowi – and its supporting parties – seems to be informal and loose. Jokowi never openly declared his support for Prabowo, even though his son – Gibran Rakabuming Raka – was Prabowo’s running mate and his supporters backed Prabowo. This informal support raises questions as to whether Jokowi will continue to support Prabowo wholeheartedly once Prabowo comes to power.

In addition, Prabowo’s political party – the Greater Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) – did not attain a majority, or even the most seats, in the People’s Representative Council (DPR). Currently, Gerindra is predicted to only have 86 seats (14,63%). Prabowo will therefore rely on the support of other parties – particularly Golkar and the National Mandate Party (PAN) – to propose legislation. Both parties have been supporters of Jokowi’s government.

This could make policy debates and negotiations, including on foreign policy, dynamic within the coalition. Prabowo may want to promote a nationalistic agenda above Indonesia’s relationship with China. But doing so would require support from other political parties, many of which possess factions loyal to President Jokowi.

There is also a second factor that we should count in: Chinese investment in Indonesia. Chinese investment has been pivotal for Jokowi’s development programs, especially during his second administration. Through the Belt and Road Initiative, China has committed to a number of infrastructure and industrial projects, including the Jakarta Bandung high-speed rail project, the Mentarang Induk Hydroelectric Project and the development of an ‘eco-city’ on Rempang Island.

These commitments have helped Indonesia strengthen its economy during Jokowi’s administration, and, in part, created a more positive image of China among Indonesians, according to a new survey from the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Therefore, politically, Prabowo may feel economic pressure to strengthen Indonesia’s relationship with China, just as President Jokowi has done, so that his coalition of supporters can continue to obtain the economic benefits of the current cooperation with China. So far, Prabowo himself has vowed to continue Jokowi’s foreign policy, including his signature industrial downstreaming policies. But it means that Prabowo has no choice other than to engage China. With its rising economic power, and its key strategic competitor – the United States – offering no viable alternative, China has become somewhat indispensable to Indonesia.

Prabowo also needs to navigate great power competition

Chinese investment is not without cost. Should Prabowo proceed to establish closer economic cooperation with China, he may have to loosen his stance on several issues, such as Chinese workers in Indonesia or China’s maritime territorial claims in the South China Sea. This would be at odds with some Southeast Asian countries’ efforts to protect their territorial sovereignty in the South China Sea – particularly the Philippines and Vietnam – who have been more outspoken against China’s militarisation in the region.

But if Prabowo wants to take a tougher stance against China, it will likely come at a cost. China’s investment in Indonesia has been primarily led by Chinese state-owned enterprises. Public criticism can lead to political decisions to divert investment elsewhere.

Of course, there is still the other great power: the United States. Prabowo, a retired general who was trained in the United States, and still has well-established connections in Washington from his work as Defence Minister, might be able to persuade the US to displace China as the major economic benefactor in the region.

But the US also struggles to advance economic cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region, and many are sceptical of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework due to a lack of investment commitment. With the prospect of Donald Trump winning the next general election and imposing an isolationist foreign policy, it is unlikely that the United States will be in a position to counter China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific any time soon.

Geopolitical tensions are likely to increase in the future between the United States and China. A more prudent foreign policy approach, and a more active role in global politics, will be needed to better position Indonesia in an uncertain international political landscape. It may even mean Prabowo is forced to play the difficult role of mediator between these great power rivals.