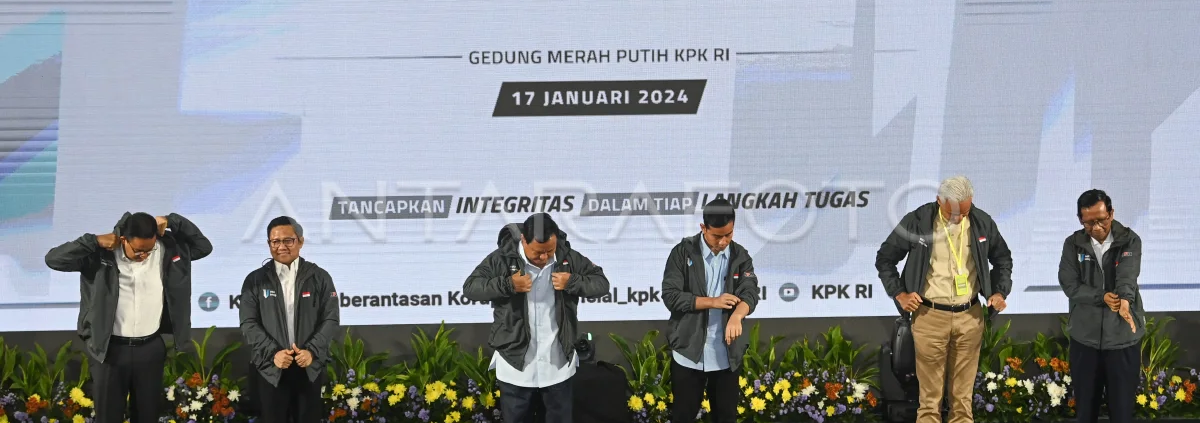

Presidential and vice presidential candidates were presented with jackets at the Integrity Pact on 17 January.

On 17 January, a little less than a month before 204 million registered Indonesian voters will cast their votes for a new president and national parliament, over 3,000 YouTubers tuned in to watch ‘The Integrity Pact’.

This was effectively a public relations stunt organised by the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK). Over the course of the two-hour Integrity Pact event, the three presidential candidate pairs each presented their anti-corruption vision for the future.

The KPK has never been in more need of regaining public trust. During Joko Widodo’s final term as president, a new KPK Law (19 of 2019) gutted the agency’s autonomy, key staff were purged, and others were embroiled in an illegal payments scheme. Most concerningly, the chairman himself, Firli Bahuri, was dismissed for ethics breaches and declared as a suspect in a corruption case involving the Minister for Agriculture, Syahrul Yasin Limpo.

So, what was the Integrity Pact and what can it tell us about the future of anti-corruption efforts in Indonesia?

What is the Integrity Pact?

In fact, this isn’t the first Integrity Pact – the KPK has offered similar forums for national and regional government institutions since 2021.

They have been pragmatic events, serving as a forum for consultation, information sharing, and strengthening the commitment of state administrators to anti-corruption efforts. Proceedings typically start with an executive briefing, followed by training and eventually certification of public servants.

However, this was the first time the Integrity Pact has been incorporated into a presidential election. The agenda was not widely published in advance, so many expected a similar format, a debate on anti-corruption, and frequent interaction between the KPK and the candidates.

Instead, the opening resembled a campaign event – a campaign for both the candidates and the KPK – replete with the national and KPK anthems, self-promoting video messages, formal presentations, and the ceremonial handing over of integrity jackets.

After one hour, the presidential candidates eventually got ten minutes each to present their anti-corruption agenda.

But a debate and scrutiny from the KPK? Spoiler alert – that did not happen.

So, what did the candidates say?

Anies Baswedan: restoring the KPK’s powers and integrity

Anies Baswedan, former academic and governor of Jakarta, spoke of reinstating the old powers of the KPK by reversing the controversial KPK Law. He also spoke of enforcing ethical and recruitment standards within the agency.

He stressed that non-compliance with the asset declaration system should have real consequences and that he would support the passing of three existing draft bills on asset recovery, party financing, illicit enrichment and the trading of influence.

He promised rewards for whistleblowers – though protecting them and putting in barriers for retaliatory defamation suits should probably come first. He also singled out sectors needing attention: public revenue, agriculture, and basic services, such as education. But he overlooked the pervasive integrity problems within other law enforcement institutions, the national police in particular, which have hampered a broader law enforcement alliance against corruption.

Prabowo Subianto: raising living standards of senior civil servants

Prawobo Subianto, incumbent Minister of Defence spoke without any notes, although they might have benefited him.

While he expressed his total commitment against corruption, promising systemic action from the top, his only major policy recommendation focused on raising the salary of senior state officials.

This will no doubt play well with Indonesia’s civil servants, but research on the effectiveness of raising salaries to reduce corruption is inconclusive. However, it is safe to say that this alone will certainly not disrupt existing corrupt networks in the bureaucracy.

Prabowo’s other policy suggestions were limited to strengthening the asset declaration system and reversing the burden of proof in illicit enrichment cases.

He did not mention the much-reduced role or powers of the KPK, suggesting he is content with the status quo of a weakened anti-corruption agency.

Ganjar Pranowo: digital administration and more coordinated efforts against corruption

Ganjar Pranowo, the former Governor of Central Java, is running with the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), which supported Jokowi in the last two presidential elections.

Ganjar proposed to restore the KPK’s investigative independence but emphasised that defeating corruption should not fall on the shoulders of the KPK alone. He argued for stronger coordination between the KPK and other state accountability institutions and more widespread use of electronic platforms in the state administration to control and detect corruption. He also suggested strengthening asset declaration and whistleblowing mechanisms.

Ganjar was the candidate who offered the broadest anti-corruption approach and the only one to mention conflicts of interest, in particular when it comes to holding multiple positions. He was also the only one to call for more transparency and reform in the police and armed forces, where corruption issues have lingered untouched since Indonesia’s democratic reformation in 1998.

But it remains to be seen how much influence Ganjar’s party would have over him if he is elected. PDI-P repeatedly proved themselves either unable or unwilling to protect the KPK throughout their 10-year support of Jokowi.

What is the future of the KPK?

Bringing presidential candidates together to present their policies on corruption is not a common feature of political campaigns around the world. The fact this event even took place shows the political power the KPK still exerts and that presidential candidates recognise corruption matters to the Indonesian public.

Candidates cannot feasibly reject an invitation to such an event, only negotiate the terms. This might explain why the event comprised 10-minute statements rather than a dialogue or even debate. Nevertheless, these 10 minutes were telling.

So, what does the Integrity Pact mean for the campaign? The event will not be hugely consequential for the outcome of the elections.

It did not leave a dent in the election discourse. Even though livestreamed by TVRI and major daily Kompas, there was little analysis of the event in the mainstream media afterwards.

The result of the elections, however, is likely to strongly affect the future of the KPK and the nature of corruption in Indonesia. Currently, Prabowo has a strong lead in the polls. Only if supporters of the other two candidates combine their votes for either Team Anies or Team Ganjar in a run-off is there a chance that anti-corruption and rule of law will be on the political agenda beyond 2024.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/djou/6521912409

https://www.flickr.com/photos/djou/6521912409