Until recently, the term emak was often associated with power, agency, toughness, mobility, freedom, resilience, independence, as well as stubbornness.

Seven months out from the presidential election, both pairs of candidates seem to have suddenly discovered the power of Indonesian women. Over the last few months, women’s voices have become increasingly prominent in the campaign.

In July, a group of women calling themselves the Militant Indonesian Mothers (Barisan Emak-Emak Militan Indonesia) protested in front of the Presidential Palace, demanding that President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo take action to reduce the cost of staple foods.

In September, they held another rally, at the General Elections Commission (KPU), calling for Jokowi to follow the lead of former Jakarta Vice Governor Sandiaga Uno and step down from office given that he had already declared himself a candidate for the 2019 race.

These so called emak-emak have been strongly associated with the #2019GantiPresident (#2019ChangethePresident) campaign and the Prabowo Subianto-Sandiaga Uno ticket. But Jokowi’s supporters have also used the term – in August a group calling itself Jokowi’s Militant Mothers (Emak Militan Jokowi) reported members of the #2019ChangethePresident movement to police for alleged hate speech.

Prabowo and Sandiaga look set to run an economy-focused campaign, and Sandiaga, especially, has shown a readiness to use women’s voices to attract votes. In public appearances and on Twitter, Sandiaga has said his economic plans will be based on the real stories of emak-emak, who he says are concerned about the rising costs that the government has failed to keep under control.

Similarly, in the legislature’s 2018 “State of the Nation” address, Speaker of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) and leader of the National Mandate Party (PAN) Zulkifli Hasan said he was “delivering a message from emak-emak” when he said that government policies were hurting households.

Who are emak-emak?

Although the term emak-emak (or emak in its singular form) has been around for some time, it has only been debated in the media recently. Many women now see the term as having derogatory connotations. Two weeks ago, the Indonesian Women’s Congress (KWI) denounced the use of the term emak-emak, and declared a preference for Indonesian mothers to be called ibu bangsa (mothers of the nation).

Reflecting how politicised this debate has now become, Jokowi soon after tweeted in support of ibu bangsa, referring to the number of women in his cabinet and the number of Asian Games gold medals won by Indonesian women.

Long before the recent sensation around the term, emak was understood by many Indonesian women (especially middle-aged women) to imply power, agency, toughness, mobility, freedom, resilience, independence, as well as stubbornness.

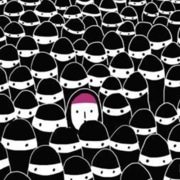

Photos shared on social media with the caption “the power of emak-emak” often depict women in situations of struggle. A typical image might show an old woman carrying a pile of wood on her head, or a woman driving a motorcycle stacked high with the results of harvest. Some images show women riding motorcycles against traffic or without a helmet. There is a sense of a tough woman doing what it takes to get the job done.

When used in this way, emak-emak seems to perfectly encapsulate what many scholars of Indonesia have often argued about Indonesian women – that they have high mobility and relative autonomy and authority, especially when compared to women in many other parts of the world.

The term emak is typically used by children in Java, Sumatra and some other islands to refer to their mothers (although in Sumatra the pronunciation is usually mamak or mak). It is generally considered an indigenous form of the term mama or mum common in urban areas of Indonesia.

Historically, therefore, many people saw the term emak as empowering. It was a reminder of the strength and authority of Indonesian women. It demonstrated how women challenge the rules and expectations that have been placed on them, including, for example, to stay at home and be preoccupied with their husbands’ and children’s needs.

But the presidential campaign has seen this notion of independence, freedom and resilience turned on its head. Political parties and their mostly male politicians are now suddenly speaking on behalf of women. When they speak of emak-emak it no longer sounds empowering – it sounds patronising. This new politicisation of the term seems to be crushing the notion of women’s independence that is strongly embedded in it.

Winning the hearts of Indonesian women

There is a reason that both presidential candidates are targeting women voters. The KPU recently announced that the number of women voters exceeds the number of male voters. And in the recent local leadership elections, women participated at a higher rate than men, with 76 per cent of eligible women voting, compared to 70 per cent of eligible men.

But politicians’ attempts to target these women are misguided. They seem to believe that women are motivated to participate in elections solely because of household concerns. Women and girls are also concerned about sexual violence and harassment, child marriage, genital cutting, equality in the workforce and, last but not least, increased pressure to conform to religious doctrines and values that restrict their mobility and freedom of expression.

As leading political scholar Ani Sutjipto recently, and correctly, observed, the depiction of emak-emak as being rendered hopeless because of economic stress is a major setback. Women’s identities are understood only through their biological roles as mothers, little thought is given to the many different ways women may wish to express their political interests. Sutjipto also somewhat depressingly observed that despite the significant number of women in the national legislature, as a result of hard-won reforms like quotas, women’s voices and interests are still being captured by men.

It is true that the beliefs and ideological orientation of women often have economic determinants. However, patronising and simplistic stereotypes of women as mothers run the risk of not being able to keep up with the transformation of women’s identity in modern Indonesia. This is happening quickly and producing new identities that often seem very different to the old stereotypes.

The campaign has a long way to go, and maybe candidates will find a more sophisticated way to appeal to women voters. Looking at things positively, at least politicians know they need to attract the votes of women. But women’s voices are not uniform, their identities are not singular. Politicians underestimate the power of Indonesian women at their peril.