Members of the Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI) and Indonesian National Police (Polri) were responsible for the vast majority of confirmed cases of torture. Photo by Antara.

Despite frequent international and national exposure, torture in Papua has been continuous and systematic for half a century. It is characterised by virtually complete impunity for torturers and consistent denial by the state.

Torture is generally considered a hidden crime but in Papua it is performed for an audience, sometimes spectacularly. It is, in fact, designed to convey a message of terror from state authorities to the Papuan public. This is in stark contrast to torture in places like Abu Ghraib prison, for example, where torture, while also a theatrical performance, was intended to intimidate prisoners, not the public.

The phenomenon of torture is inseparable from the political conflict in Papua, one of the longest-running conflicts in the Pacific. It roots extend back to the 1940s and relate to the power struggles that accompanied the end of Dutch colonisation in Southeast Asia. Although the Dutch recognised Indonesian independence in 1949, they continued to claim Papua as Dutch New Guinea, and it was not until 1962 that the colonial administration withdrew. They did so in accordance with the New York Agreement, which gave the United Nations a mandate to supervise a referendum for Papuans in 1969, an event that led to Indonesia annexing the former colony.

Indonesia asserted control over Dutch New Guinea in 1963 and, almost simultaneously, the embryonic Papuan state also asserted its own sovereignty over the former Dutch territory. The referendum – the so-called Act of Free Choice – is considered by most Papuans to have been deeply flawed and the rival claims to territorial sovereignty have never been resolved.

My research has identified 431 cases of torture in Papua between 1963 and 2010. To confirm them, I conducted 214 interviews and cross-checked them with field visits and secondary sources.

Analysis revealed that 19 per cent of these cases took place in the Special Autonomy era (since 2001), nearly half (42 per cent) occurred during the relatively brief reform (reformasi) era (from 1998-2001), 37 per cent occurred under the New Order (1967-1998), and only 2 per cent occurred under Soekarno (1963-1967). This does not necessarily mean that levels of torture were significantly higher during reformasi. The militarisation of Papua and poor record keeping under the New Order could easily have prevented accurate accounts of torture during the 1960s, while more intense international and national scrutiny during reformasi could have led to the higher numbers of confirmed cases in that period.

The perpetrators of torture were mostly state officials. 65 per cent were members of the Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI), 34 per cent were police officers, and only 1 per cent were members of militia groups. The victims, meanwhile, were mainly highlanders living in rural areas. They were predominantly male, and farmers by occupation. Only two survivors or victims were members of the secessionist Free Papua Movement (OPM). The overwhelming majority were ordinary civilians who were not involved in the armed struggle.

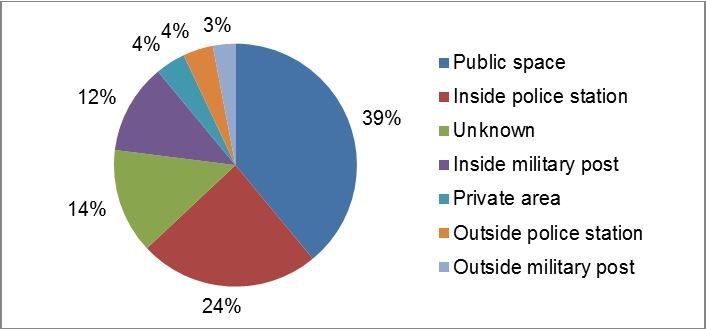

The most remarkable finding was, however, that the dominant pattern of torture in Papua involved public presentation of state brutality. Nearly 40 per cent of all cases occurred in public places, such as streets, schoolyards, parks, and open spaces in villages, or in government, military and police facilities. Many military and police stations in rural areas of Papua are basic wooden constructions, and the public can often observe what is occurring inside them. It is therefore possible that up to 82 per cent of torture cases were, in one way or another, performed in public.

The public nature of much of the torture confirms that it was deliberately designed by the Indonesian state to communicate shock and awe. A gruesome YouTube video that emerged in October 2010 demonstrates this. It depicted the torture of four Papuan highlanders by a group of Indonesian soldiers in Mulia, Puncak Jaya district, in Papua. Soldiers burned the genitals of one man, held a knife to the neck of another, and forced them to confess that they were members of the OPM. As well as being recorded, the torture was also witnessed by the local community, who were just 50 meters from the scene.

The case was widely covered in the international media and the Indonesian government was forced to take action. Seven soldiers were found guilty and sentenced to between five and 10 months in prison – but only for disobedience, not torture. The sentences of three of the soldiers were reduced to three months on appeal. The others did not appeal.

This high level of impunity encourages the Indonesian state and security apparatus to exhibit brutality in public. The public has been so controlled, cowed and generally colonised that it sees little chance for any opposition, and deems reports and charges futile. On the rare occasions when torture cases are brought to human rights courts, Indonesian human rights laws have been easily avoided. In the Abepura case of 2000, for example, the Human Rights Court simply failed to address the element of torture, despite the evidence presented.

Interviews with perpetrators revealed that torture in Papua had nothing to do with extracting information, forcing confessions from the victims, or simply punishing them. Rather, it was about executing power in a theatrical way. As one military official told me, he and his group did not want to kill their victims but just to “make them [feel] really, really bad.”

Torture in Papua is not executed by a few “bad apples”. Rather, it constitutes part of a larger strategy of domination by the Indonesian state in which the practice of torture is sanctioned and part of policy, underpinned by the rationale of sovereignty. The Indonesian state and its agents act together and in a systematic way. This includes the incidents of torture themselves, as well as the absence of legal consequences.

A small flicker of hope remains, however. Even though the law and justice system seems paralysed, caregivers are not. Notwithstanding the state’s policy of terror, they manage to maintain their agency and more importantly, to organise and consolidate resistance to oppression in various forms. This collaboration between the caregivers and survivors can change the theatre of torture from a confrontation between survivors and the state to a triangle of survivors, the state and caregivers. It is in this triangle that the limitations of sovereignty and governmentality become visible.

This blog post is based on a journal article previously published in the International Journal of Conflict and Violence.