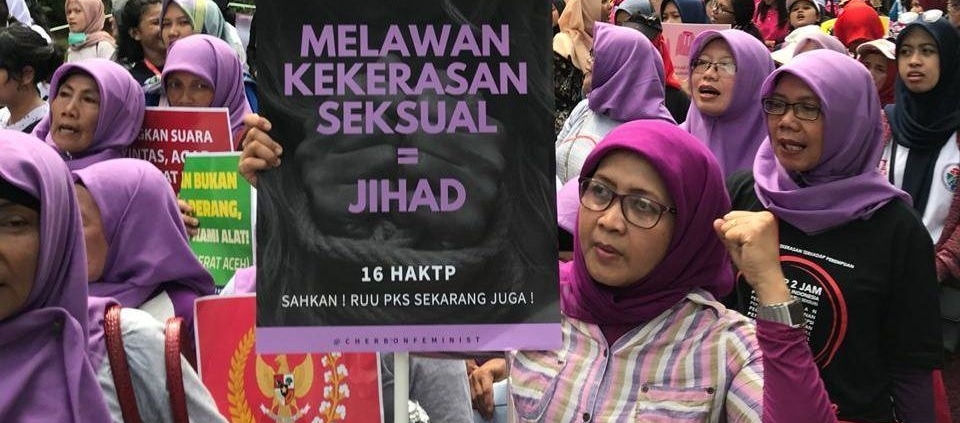

Participants in the march against sexual violence in 2018. Photo by Tunggal Pawestri.

After more than a decade of advocacy by gender activists, Indonesia’s national legislature (DPR), passed a landmark law on sexual violence on 12 April, six years after deliberations began.

The law, now known as the TPKS Law, is not a “gift” to women as DPR Speaker Puan Maharani said when it was passed. The result of a long and hard struggle inside and outside the legislature, it simply establishes basic and necessary human rights protections – the bare minimum. It is an essential element for a more civilised nation.

The National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan) began preparing a draft of the law in 2014. But its origins extend as far back as 2010, when Komnas Perempuan began discussing the need for such a law to respond to escalating cases of violence against women.

Since then, Indonesian gender activists and broader civil society have tirelessly advocated for the law, conducting regular meetings with the DPR’s legislation body, and holding countless public discussions, social media campaigns and public demonstrations, including marches against sexual violence. Even major beauty brands were recruited into the campaign. The bill also featured prominently in the demands of student and civil society protestors during the massive Reformasi Dikorupsi (Reform Corrupted) demonstrations in 2019.

Discussion of the bill has been extremely heated at times, with serious opposition from conservative groups. The Islam-based Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), for example, confusingly argued that because the bill did not outlaw sex outside marriage, it would promote sexual promiscuity and “deviant sexual behaviour”.

Growing public anger over high-profile cases of sexual abuse, a strong statement from President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo in January urging the DPR to pass the bill as soon as possible, and targeted advocacy from women’s rights activists finally saw it get across the line. In the end, it was supported by all political party factions in the DPR – except PKS.

Somewhat remarkably, given recent legislative history, the last phase of deliberations was marked by open and participatory discussions with civil society and the public. Suggestions and input from women’s groups, especially service providers, were accommodated by the DPR and government representatives. If all legislative drafting processes were this open, Indonesia would have much better laws than it does, and be much closer to closing the gender equality gap.

There are several breakthrough legal elements in the law. First, it recognises nine types of sexual violence not covered in existing laws: physical and non-physical sexual abuse, forced contraception, forced sterilisation, forced marriage, sexual torture, sexual exploitation, sexual slavery, and online sexual violence (Article 4).

An earlier draft also described rape and forced abortion as offences under the law. These were not included in the final law because they are already covered under the Criminal Code (KUHP). However, the TPKS Law does recognise rape as a form of sexual violence, and acknowledges sexual violence can occur within the household (a euphemism for marital rape) (Article 4(2)(h)).

Crucially, the law also acknowledges that sexual violence often results from a power imbalance that causes victims to be more vulnerable to abuse (Articles 6(c) and 11).

Importantly, the law states that police, prosecutors and judges who handle cases of sexual violence must have integrity and competence, and a victim-centred approach to case handling, in line with human rights principles (Article 21(a)). The law therefore requires that they participate in specialised gender training (Article 21(b)).

This is a significant advance. Many police, prosecutors and judges have extremely limited exposure to training on gender equality. In fact, insensitive and stigmatising attitudes from law enforcement officials are a major cause of widespread under-reporting of sexual abuse. When victims of sexual abuse face scepticism or victim-blaming from police and other members of the justice sector, it can exacerbate the trauma they face.

The law addresses this specifically, stating that justice sector officials must not seek to justify wrongdoing, victimise, or make judgements about a victim’s lifestyle or sexual experience (Article 22). In reality, however, it will take a huge amount of training to reverse these attitudes and ensure victims are properly supported throughout the criminal justice process.

The law also expands the forms of legally recognised evidence. The Criminal Procedural Code (KUHAP) recognises five types of legally admissible evidence: witness testimony, expert evidence, documents/letters, indications (petunjuk), and testimony of the subject/accused. The TPKS Law now makes it clear that “documents” includes letters from a psychologist or psychiatrist and medical records (Article 24).

This is a critical breakthrough, as law enforcement officials have sometimes used the excuse of a lack of sufficient admissible evidence to refuse to process cases. A victim statement and records from a medical professional should now be sufficient to see cases processed, and will hopefully encourage more victims to come forward.

Arguably the most important aspect of the law is its strong focus on victims. The law clearly states that victims have: a) the right to have their case processed; b) the right to protection; and c) the right to restitution and recovery (Article 67).

Significantly – and despite past suggestions by some of the country’s most senior legal officials – the law states that cases of sexual violence cannot be resolved through alternative dispute resolution or restorative justice approaches (Article 23).

The law also states that victims should be accompanied by a legal representative, sexual violence service provider, medical and mental health professional, or representative from the Witness and Victims Protection Agency (LPSK) at all stages of investigation and trial (Article 26).

Importantly, the person accompanying the victim is subject to legal protection too (Article 29). The law states that the person accompanying the victim cannot be charged under criminal or civil law. This is significant because in the past people accompanying victims have often faced legal threats, particularly when the alleged perpetrator is a person of power.

The law also provides for temporary protection of victims (Article 42). It states that within 24 hours of receiving a report, police can provide temporary protection for the victim for up to 14 days, involving distancing the alleged perpetrator from their victim, restricting the perpetrator’s movement, or limiting specific rights.

Under the TPKS Law, victims also have a right to medical and mental health recovery services, as well as restitution or compensation (Article 30). Compensation can be provided for loss of income or assets, suffering, medical or psychological costs. Law enforcement officials can seize the assets of the alleged perpetrator to cover the costs. The law even establishes a “Victim Trust Fund” to cover the costs of compensation if the perpetrator’s assets are insufficient (Article 35).

All things considered, the passage of this law is a momentous achievement for the women’s movement in Indonesia. Victims, service providers and activists should take a moment to feel proud of the extraordinary efforts they have expended over so many years to reach this point.

But the struggle is not over yet. The women’s movement needs to keep up the pressure so that the all-important implementing regulations live up to the promise of the law. They also need to ensure that officials receive the training dictated by the law, and most importantly, the law is publicised widely so that citizens are aware of it and the protection it offers them.

And there are other threats on the horizon. Legislators are also still determined to pass a revised Criminal Code (RKUHP), which still contains some articles that will further restrict the rights of women and sexual and gender minorities. Civil society must also closely watch the planned revisions to the Law on Information and Electronic Transactions, which has previously been used against victims of sexual abuse.

It is true that Indonesia has achieved a significant milestone in the progress toward gender equality, but this is only the beginning. There are more battles waiting in the struggle to maximise protection for victims.